Kishi enables the reader to empathize and understand this time in United States history, not only as an event characterized by statistics and faceless facts of the past, but also because his is the story of many that has been kept hidden away and only told with the continuous encouragement of family and community and with small glimmers of hope and good that came out of Manzanar.

The first thing he makes abundantly clear is that telling his story has been a trial in itself, a sentiment that seems to be common among the Japanese Americans who lived through World War II, and the American concentration camps. With this in mind, the reader is made aware that the effects of the camps could not be forgotten, even after the gates closed, the barracks torn down, reparations paid, recognition given for honorable military service, and with the birth of new generations. Kishi’s book is the product of numerous attempts and struggles to express what happened to him and his family.

His story begins with the radio announcement about the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan. Despite the familiar beginning, the focus on a single Japanese American family’s experience illuminates the real fear and uncertainty that was felt among the whole group of people who were of Japanese ancestry. Instead of the simple facts like “…prominent members of the Japanese community were arrested,” the reader is given a more emotional experience, learning that Kishi’s father, and head of the household, was seized, handcuffed, and taken away from their family nursery in a black sedan by FBI agents without knowing why or where they would take him. Details like this give a far more fearful, but realistic depth to the history.

Kishi continues on to describe the numerous struggles he and his family faced in preparing to be forcibly removed from their home in Santa Monica due to Executive Order 9066, from having to destroy precious Japanese cultural items to having to drop out of UCLA. From his personal experience, it’s easy to see that hardships began long before he ever actually stepped foot into Manzanar.

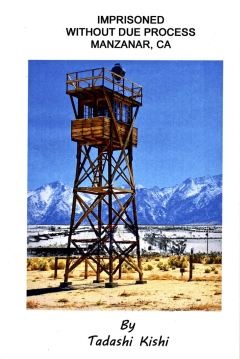

The story of how Kishi arrives and settles into living at Manzanar has many punctuating details that encapsulate his and his mother’s struggles. All guises of normality that are described by the phrases “food, shelter, and other accommodations as may be necessary,” are thrown to the wind when he explains the shock from seeing things like the small and dusty room designated to his family with rucksacks filled with hay for mattresses and the deterioration of family structures and routines due to things like the lack of need for his mother’s cooking because they ate in communal mess halls. Through numerous other stories of his life in camp the reader can only begin to understand what kind of hardships and horrific experiences had to be endured while living in Manzanar.

Despite the hopelessness and sadness that went along with living in Manzanar, Kishi does his best to find some good and explain how people were constantly trying to make the best of their situation, truly exemplifying the Japanese values of gaman (to endure), ganbaru (to persevere), giri (duty), oyakoko (loyalty), on (filial piety), and kodomo no tame ni (sacrifice for the children). For Kishi, in particular, he contributed to daily life by working hard and becoming a physics teacher for Manzanar High School. His efforts culminate in his pride in one student, Dr. Gordon Sato, who graduated from his class and went on to dedicate his life to saving an African country from poverty. Kishi also highlights the lives and legacies of Joseph Kurihara and Sadao Munemori.

Although his book is short, it is one that brings a common story among the Japanese American community to striking reality through the eyes of one individual. Tadashi Kishi gives readers insight into one of the darkest chapters of U.S. history and provides a warning to never forget or let it happen again, while also keeping a hopeful outlook for the future.

*This article was originally published on The Manzanar Committee Official Blog on July 6, 2017.

© 2017 Carly Lindley