After you were in training, you were aware that it was leading up to the occupation of Japan?

Yes, we expected that all along. The first thing was we got shipped out of San Francisco in July of 1945 and we were sent to the Philippines. They had ATIS–Allied Translation and Interpreter Section–part of the U.S. army and we were stationed close to Manila. We were there about the end of July and of course the atom bomb was dropped in the middle of August. So in September they sent us right into Japan as part of ATIS.

What were some of your memories of being there?

Well, one of the most vivid memories I have of it is when we went by ship to Yokohama, and it’s about 20 miles from Tokyo. They had some of the big government buildings still standing there in Tokyo. We were stationed in the NYK (Nippon Yusen Kaisha) building. That trip from Yokohama to Tokyo was by train. And for 20 miles it was all black, all burnt out. It was incredible. I think actually the death toll in Tokyo was worse than in Hiroshima because of the incendiary Everything in Japan was made out of paper and wood so everything burnt up like paper. They say it was so bad that there was just no oxygen and people died from a lack of oxygen. It was so severe, the fires that they had.

A lot of MIS veterans remember the children wandering around, looking for food. Do you remember seeing a lot of kids?

Yes I remember that, I remember those kids. They used to go into the subway at nighttime because it was so cold. We went into the first winter there in Tokyo. There were a lot of homeless kids, small kids, just running around looking for whatever they could find. It was pretty sad.

Interestingly, us Nisei, we looked just like the Japanese people but we were wearing American uniforms. And so they treated us really well. We got to be friendly with quite a few of them.

Did you ever get a sense if they were grateful for you being there?

Well I don’t know if they were grateful for our being there [laughs]. We beat them. They were vanquished. They accepted those of us who could speak their language quite well. And we visited quite a few people who we got to know over there.

Your services were required to translate Japanese military documents?

Yeah, all military stuff. There were code books and things that we translated. I don’t know how much I translated, I don’t think very much, I just didn’t have that much Japanese background.

Were you part of any interrogations?

I was assigned to a British major. I was in the General Headquarters building, which was the Daiichi building, where General MacArthur was. That thing was only about six stories high. I was stationed on the bottom floor, interpreting for this British major. We went to the prison there and saw quite a few of the prisoners. I had to interpret for this British Major who was looking into the Black Dragon Society.

That was a famous sort of a secretive society in Japan before the war. I’m not sure if it had military people but this guy was a civilian that we went to interview, he was the head of it. They offered us tea, the British Major wouldn’t drink it, he was so scared he was going to get poisoned. I had no problem drinking the tea. [laughs]

How would you characterize your experience in Japan? Was it upsetting to see what the military did or did you just feel like you had a job to do?

I think I just really felt like I had a job to do and if we had some translating or interpreting we did that. Nothing profound, I’m sure. We just enjoyed our stay in Japan. Right before I left Japan, I got a leave and went to visit my relatives in Wakayama in 1946. Of course I had never met any of them. And my father, he came in 1903, but he never came back to Japan even once. Apparently he just didn’t care to go. But I went to visit them, and I just felt like I went home.

They welcomed you.

Yeah, they did. They were very poor, everybody was very poor in Japan. There was nothing there, you know. When we visited some people in Tokyo, they would serve us sweet potato–baked sweet potato sliced–that’s all they had, basically. That’s the other thing I remember very clearly. All these young girls probably in their early teens, would carry a knapsack, with their belongings in it and going to the country to barter for food. And most of the food they could barter for was sweet potatoes. I remember that very clearly.

Even though they were poor, were you relieved that your family wasn’t too affected by the war?

It was an intact area and the people were better off there than in Tokyo. My father’s nephew sort of took us around and he was in the service. He was one of the lucky ones that got back from Manchuria very early. So he was back by the beginning of 1946. He was very fortunate.

As that was happening, what was going on in Amache with your family?

Amache was closed towards the end of 1945. My folks came back I think in April of 1945.

Still relatively early.

And our house was shot by people who didn’t want us back. There are still bullet holes in the house. There were several shootings that went on during that period of time in April, May in 1945. My brother came back from the service, he got drafted after I went into the service, he’s older than I am. He came home to try and get some help from the local law enforcement. He actually went before the supervisors and asked them for help to make sure this kind of thing doesn’t happen. But they said they didn’t have any money and nobody wants us back anyway [laughs] So they didn’t get involved.

Did you feel afraid for your parents?

Well, we were a little upset with our house being shot, you know. But there’s nothing you can do when you’re in the service and far away.

I imagine that’s really unsettling.

Yeah, it was a little unsettling at the time that such a thing could happen.

While in camp, did your parents farm?

My father had Bright’s disease, and that’s kidney disease before the war. So my brother was actually going to UC Berkeley for one year when had to come home to help on the ranch. So we went into the camp my father was not well. Of course, he didn’t do anything. My mother used to get food from the kitchen and sort of prepare it on a hot plate in the barrack for him so he would have food that wasn’t salty and stuff.

And so he didn’t have to get medical treatment?

I don’t know if he had any medical treatment, I don’t think he did. There was a hospital there but it wasn’t much of a hospital. So he survived through it and came home and he died in 1945, about six months after he came home. So he lived through it until he came back which was wonderful for him. At least he got back.

How old was he?

I think he died at 64. My mother lived to be 86.

In camp, when you were there, what were some of your memories?

Our church is just a quarter of a mile from here and that’s why they came after us. But we also were farmers and we had trucks, so we took a lot more than we could carry. They never objected to us taking additional things if we got it into camp. From there when they went to Colorado, they just put it on the train and took it all for us.

That sounds rare.

It was pretty rare. There were a lot of people that did, in the area. My mother took a sewing machine, and I had my saxophone, normally you wouldn’t take something like that. Took a lot more than most people were able to.

I’ve never heard of anyone being able to put extra things on the train.

We just took it over there and it was all unloaded in the assembly center and we took it into our barrack and when we left, we took it out to where they were shipping things and it all went to Colorado.

So how long were you actually in Amache?

I was there from September of 1942 to until November of 1943 when I went into the service. I didn’t turn 18 until I was a year in camp. I went into the assembly center, the notice came out on the walls and said you had to be there by a certain date. Well, the date was May the 13th, 1942. That was my 17th birthday. They had put up enough barracks to house about 5,000 people in Merced.

Were you planning on going to college?

I had hoped to go to college. My senior year in high school was in camp. My senior year was basically a lost year for me because they started late, we didn’t start until November. It was sort of a high school and they were all people within the camp itself that became teachers. We had a lot of well-educated people in camp but I didn’t learn anything. I lost my senior in high school. I really found out when I went to college, in Berkeley. I had no advanced algebra, I had no chemistry, I had no physics. So the classes I took had to have that as a basic understand and I had to learn all of that on my own, so it was a tough couple of years for me in college.

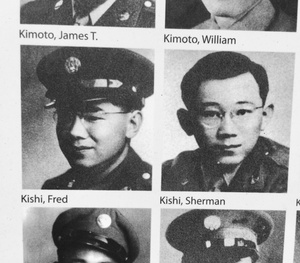

The military did come to recruit, for the 442 and for MIS. I remember when they first came, I wasn’t 18 yet. A lot of my friends did volunteer and went into the service.

You were lucky.

Yeah, three of our community didn’t come back. I think they got killed in France when they fought for the Lost Battalion. I think in one of those fights, we lost three young men.

I’ve heard from some MIS veterans that they felt lucky that they were spared. It could’ve been any one of them to go into the 442.

Yeah, it could’ve been very well. But we lost a number of men in the MIS as well that were in the fights in the Pacific. It wasn’t completely safe, in fact it was dangerous because they had a Japanese face and they had to be careful of their own men. In fact one guy that was in Livingston, he was a Sergeant, and he became the caretaker for one of the translators because they had to have some American white guy with them to make sure they would be safe. It was not a good thing.

But they did a tremendous job in the Pacific as well. And most of that was done by the Kibeis. They were the ones that did most of the translating and interpreting because they knew the language so well. I think most of the Niseis who didn’t know the language well like myself did most of the writing, who probably understood enough to know what was being said.

How was coming back home after the war? Did you experience any discrimination?

You know, that’s interesting. We really didn’t experience very much of that. I think it happened before I came back. There were resolutions passed in the town of Merced, Livingston, Turlock, saying they didn’t want the Japanese people back. This was in 1945. And there were some incidents of people that came back early and there were other places that also got shot. And other incidents where the barber wouldn’t give them haircuts and things like that. Those things happened.

As a matter of fact there’s that story about Dan Inouye, the senator who had only one arm. He tried to get a haircut and they wouldn’t give him one. They said, “We don’t give Japs haircuts.” Can you imagine? He’s in uniform, and he lost an arm in the service and he had all those medals on his chest. It’s just the hatred that happens.

Do your children know your story?

We didn’t talk to the kids about camp life, we talked about camp life with our friends but we never talked about camp life to our kids. They basically learned it in school. We didn’t really feel very comfortable about it until after redress was developed and Reagan signed the bill. After they gave us the redress, it just really relieved all of us who had been in the camp. Because camp was sort of a feeling of shame, that you had to be in a place like that. So we didn’t talk about it. But after that, we felt much more freer to talk about it. There’s always the chance of something like this happening again. We need to keep speaking about it and keep it in people’s minds that it did happen.

Lastly, do you mind sharing the story of how did you and June met?

That’s a story I always tell when I go to speak. Remember how I said there was a curfew, we couldn’t go more than five miles? June was actually born in Cortez which is seven miles from here but they had moved to several places in the area before that. Just before the war she was more than five miles away. So, I went to visit her, and I didn’t get caught because there’s no sheriffs out, no police out, so I got along fine.

She’s a couple years older than I am and she had finished school and was working. I sort of went around with her at the high school but not that much. And so we were in the same camp, went to the assembly center together and used to see her around at Amache all the time. So, I didn’t get caught and she was my girlfriend. We got married later and in September of this year we’ll be married 72 years. Every time we tell the story the kids clap.

Listen to the interview here:

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on June 26, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida