My post about this discovery was seen by my Facebook friend June Aochi Berk, who is one of the leaders of a coalition to keep alive the history of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station. June asked for my approval to give Kunitomo’s name to Russell Endo, a member of this coalition and a retired University of Colorado professor who was conducting research at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. A few weeks later, Professor Endo emailed me that he found some three dozen pages of documents about my grandfather in the National Archives. The Professor then started sending copies of documents to me in small batches.

The FBI is after my grandfather.

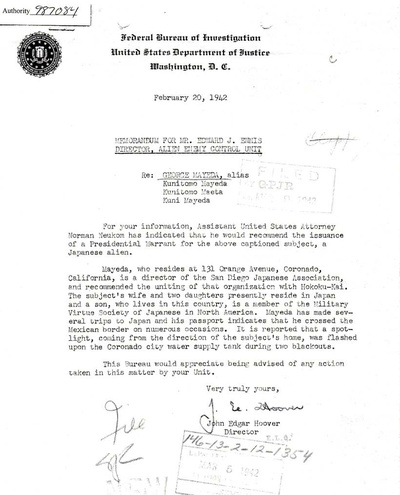

The very first document took my breath away. It is a memo on FBI letterhead dated February 20, 1942 to the Director of the “Alien Enemy Control Unit” specifically referencing “George Mayeda, alias Kunitomo Mayeda”—my grandfather. The memo recommends the issuance of a Presidential Warrant for the arrest of Kunitomo and it is hand-signed by none other than FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

And what is the basis for Mr. Hoover’s conclusion of urgency that my grandfather should be arrested, even before the general incarceration of Japanese Americans from the West Coast takes place? It is because: (1) Kunitomo was a director of the San Diego Japanese Association and recommended uniting that organization with another called Hokoku-Kai, which the FBI apparently suspected of harboring immigrants loyal to Japan; (2) his wife and two daughters reside in Japan; (3) one of his sons—my father—was a member of an organization called the Military Virtue Society of Japan in North America, a group that practiced traditional Japanese martial arts such as Butoh and Kendo; and (4) “it is reported that a spotlight, coming from the direction of [Kunitomo’s] home, was flashed upon the Coronado, California city water supply tank during two blackouts” after Pearl Harbor.

Subsequent documents revealed that Kunitomo was arrested on March 19, held overnight at the San Diego County Jail, sent first to Terminal Island Detention Station, then transferred to Tuna Canyon, before eventually being transferred to Santa Fe. During this process, no charges were ever filed against him for spying, espionage, sabotage, or any other crime. Instead, a hearing was held in Santa Fe, an apparent attempt to comply with the 1929 Geneva Convention, thereby revealing that the government viewed the arrested Japanese aliens as essentially “prisoners of war.”

Based on his research and his own grandfather’s experiences, Professor Endo believes these hearings were designed more to justify the subject’s arrest and continued imprisonment than to assess any actual risk of disloyalty to America. There was no due process and no defense counsel allowed. A family member was permitted to attend the hearing but in Kunitomo’s case, he had no one present to help. So apparently, the hearing relied principally on an FBI Report on my grandfather.

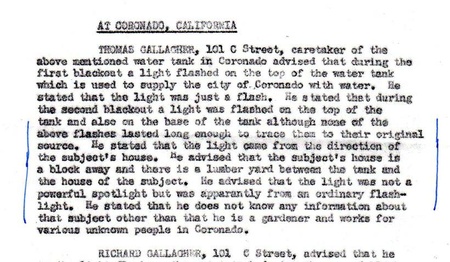

The FBI Report is 15 pages long, single-spaced. It is notable both for its detail as well as the lack of any significant evidence against Kunitomo. On the one side was the fact that Kunitomo once gave a speech urging the merger of the San Diego Japanese Association and the San Diego Hokoku-Kai; that a “Confidential Informant” advised the FBI that a week after Pearl Harbor, “a reliable informant” had reported to the first informant that during blackouts on December 10 and 11, 1942, “someone turned a powerful spotlight onto the high-water tank located . . . at Coronado, California;” and that Kunitomo had once given thirty dollars to the “long-term military relief fund” that was sent to Japanese Army and Navy relief ministries in Tokyo. Despite a thorough search of Kunitomo’s home, exposing a roll of film found on the premises, and translating a dozen letters written in Japanese found at the home, the FBI turned up nothing that could be used against Kunitomo. Indeed, another section of the report indicates that the caretaker of the aforementioned water tank advised that “the light was not a powerful spotlight but was apparently from an ordinary flashlight” and that it was not on long enough to trace back to the original source, other than to note that Kunitomo’s house was a block away from the water tower.

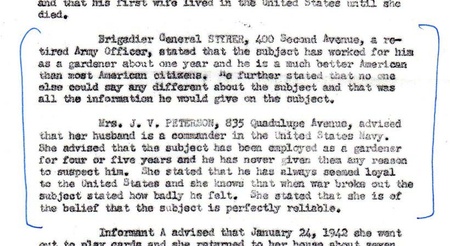

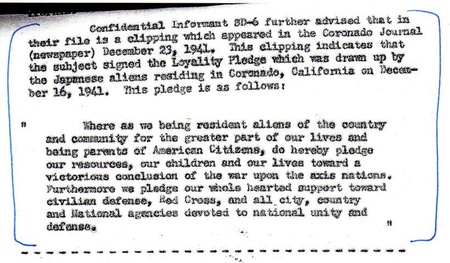

But the remainder of the FBI Report contains numerous pieces of exculpatory evidence including that a few days after Pearl Harbor, on December 16, 1941, Kunitomo signed a Loyalty Pledge that was drawn up by Japanese aliens residing in Coronado, stating that the aliens “do hereby pledge our resources, our children and our lives toward a victorious conclusion of the war upon the Axis nations.” The report also noted that Kunitomo’s oldest son, my uncle Al, had enlisted in the U.S. Army shortly after Pearl Harbor. It also contained excerpts of interviews from the gardening clients of Kunitomo, including a retired Brigadier General who stated that Kunitomo “is a much better American than most American citizens,” and the wife of a current commander of the United States Army who advised that Kunitomo “has never given them any reason to suspect him” and that “he has always seemed loyal to the United States.”

Professor Endo believes these hearings were conducted with the reversal of the usual presumption of innocence; instead, the detained “enemy aliens” were presumed to be guilty of complicity with the Japanese enemy unless they could prove their innocence. Since Kunitomo was not able to prove his loyalty to the satisfaction of a government that was inclined to view all Japanese as suspicious, he was held for the duration of the war. My grandfather eventually asked to be repatriated to Japan where he could be with his wife and three of his kids. He knew that this meant separation from and possible estrangement with his two eldest sons—one in the U.S. Army and the other, my father, having left the Poston camp in 1944 to enroll in college in Chicago. But Kunitomo felt he had little choice since he had been imprisoned by the government for years without charges, experiencing the full brunt of racial discrimination in its purest form.

The impact of wartime confinement

The Mayeda family story is like that of so many others during the war; each with its own traumas and challenges but most sharing deep pain, financial loss and brutal family conflicts. Over 120,000 Americans lost their homes, businesses, personal belongings, and most valuable of all, their sense of personal dignity. Many, including my father, had difficulty speaking about their experiences being incarcerated. Even though they did nothing wrong, many internalized a sense of shame for decades after the war.

For as long as I can remember, my father would conspicuously display an American flag at our house on all national holidays. Throughout my childhood, our family car was always an American model—Chevrolet, Buick, Chrysler, Cadillac—even as Toyotas and Hondas were becoming popular, especially in Los Angeles. It only occurred to me much later in life that my father seemed to avoid being associated with Japanese products.

It was not until 1988, after President Reagan signed legislation providing a formal apology from the government for the mass incarceration and token monetary reparations, that my father began to speak more about his experiences during the war. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 officially proclaimed the wartime confinement of Japanese Americans under Executive Order 9066 was a “grave injustice…motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” It was almost as if my father was now freed from the shame that he had felt from being locked up by the government.

The stigma caused by the mass incarceration had a major impact on the Japanese American community, although affecting each family in different ways. But it demonstrates the powerful, multi-generational impact that the full force of governmental action can have when targeting particular communities.

Could it happen again?

It is now widely accepted that the forced relocation and incarceration of Americans of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast during World War II was one of the biggest blights on the Constitution in our nation’s history. No Japanese American, citizen or alien, was ever convicted of espionage, sabotage, collaboration with the enemy, or similar charge during the war. Conversely, thousands of Japanese American Nisei (including my uncle Al Mayeda) served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the 100th Infantry Battalion, or the Military Intelligence Service, proving their loyalty to the United States and suffering tremendous casualties, even as their parents were kept behind barbed wire on American soil.

The mass incarceration, curfew, and related orders were challenged during World War II and upheld by the United States Supreme Court on the basis of “military necessity” in cases brought by Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Min Yasui. Decades later, those convictions were overturned by a legal process called a Writ of Coram Nobis when National Archives research revealed that the Solicitor General (the government’s lawyer) withheld from the Supreme Court official reports that there was no evidence that Japanese Americans were acting as spies or otherwise constituted a threat to the United States. Nevertheless, those Supreme Court opinions in Korematsu v. United States, et al., are still on the books, ready to be invoked by the next administration who can mount a claim that some curtailment of some people’s constitutional liberties is justified in order to “keep America safe.”

So can it happen again? Have the conditions of fear of terrorism and scapegoating of Muslims today risen sufficiently for someone to try to use a military necessity or public safety justification to infringe upon the civil liberties of Muslim Americans? Recall that days after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, President George W. Bush made it a point to state that American “Muslims make an incredibly valuable contribution to our country . . . and they need to be treated with respect. In our anger and emotion, our fellow Americans must treat each other with respect.”

Can anyone say with confidence that President Trump’s reaction to a major terrorist attack in the United States by Muslims would elicit a similar measured response? Based on his past statements and conduct, it seems far likelier that President Trump’s response to a major terrorist attack on his watch would veer closer toward World War II-era curfew and internment orders than toward urging restraint and strict adherence to the Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

And if an effort were made to register, imprison and/or conduct surveillance of Muslim Americans, the Japanese American experience teaches that even mundane activities such as studying Arabic, exchanging letters with relatives in the Middle East, being a leader in a mosque, or maintaining cultural traditions from a predominantly Muslim country could be deemed suspicious and provide cause to trigger “if you see something, say something” reporting.

In such event, it will be incumbent upon all American patriots, those who value the Constitution and its guarantees, to speak out against any such failure of political leadership. And it will be crucial at that time to listen to the stories of the Americans of Japanese ancestry who have personal experience with the dangers of racial prejudice and wartime hysteria. We love this country and cherish the Bill of Rights, and our family stories contain profound lessons that must be retold to safeguard the constitutional liberties of all Americans.

* * * * *

Editor’s note: Discover Nikkei is an archive of stories representing different communities, voices, and perspectives. This article presents the opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of Discover Nikkei and the Japanese American National Museum. Discover Nikkei publishes these stories as a way to share different perspectives expressed within the community.

*This article was originally published on the Huffington Post on September 13, 2017 and modified for Discover Nikkei.

© 2017 Daniel Mayeda