It took me three months to get used to the Colonial language

At the end of 1991, at the height of the bubble economy, I was working in Tokyo for a company listed on the second section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, and for some reason I decided to start working for a Japanese-language newspaper.

When I had an interview with people from the Tokyo branch of the Paulista Shimbun, a Japanese-language newspaper in Brazil, I was told that "everyone in the Japanese community speaks Japanese, so it'll be okay even if you don't understand Portuguese at first," and I easily believed it.

However, my expectations were completely betrayed. I arrived in São Paulo in April 1992. To be honest, it took me three months to get used to the Japanese dialect used in the Japanese community, called "Colonia language."

Brazil is generally written as "Bakukoku," but this is not very common in Japan. In the past, Brazil was written in kanji as "Bakusai," so this is the common spelling in Japanese newspapers.

Furthermore, the state of São Paulo is a "holy state" because its name means "Saint Paul," the apostle of Christ. The state of Rio Grande do Sul is literally translated and shortened to "Southern Grande State," the state of Rio Grande do Norte to "Northern Grande State," and the state of Mato Grosso do Sul to "Southern Mato State."

It's okay to memorize written language. The most difficult thing was everyday "spoken language." Unfortunately, this doesn't remain as "written material," so you can't study it later. You have to memorize it by throwing yourself into it.

For example, when I asked a postwar immigrant for directions in Oriental Quarter, he told me, "Take the onibus at Esquina there, pay the cinquentà centavo, and get off at the stop at Praça da República," and I held my head in my hands, wondering, "Was that Japanese?"

Also, in the past, there were many people here and there who would refer to themselves as "Yo ha", but now it's almost extinct. It's said that "Yo" is a corrupted version of EU (first person pronoun), but I liked the humorous sound of it sounding somewhat like a "noble person".

The Kyushu-like dialect "○○ wo youshikikiran (I won't finish it)" is also frequently used by people, and not just those from Kyushu.

What I realized was that this was a kind of Japanese version of a "creole language." A creole language is a language that was created naturally among merchants who could not communicate with each other and that came to be spoken as a mother tongue by the children of the speakers (Wikipedia, November 24, 2016).

It feels like an intermediate language between the second and third generation immigrants, for whom Portuguese is the main language, and the first generation immigrants who continue to insist on using Japanese.

Even in Japan, there are unique expressions in each local newspaper.

This kind of unique expression is not uncommon in local Japanese newspapers, but since it is within the country, it is merely considered a "dialect."

For example, when reading local newspapers in the Tohoku region, such as the Aomori newspapers To-o Nippo and Iwate Nippo, you will find unique expressions for "snow."

- Compacted snow is called "packed snow."

- Overcoming snow is called "Ketsuyuki"

- Using snow like at a ski resort is called "snow utilization."

- In cases such as snow festivals, the participants are given the title "Oyasuki" (parent snow) to promote their love for snow.

- The Shinano Mainichi Shimbun also reported on "warm winter and little snow," "wet snow," and "snow removal."

Another thing that impressed me was how the Kyoto Shimbun newspaper described entering Kyoto as "jouraku." Even now, that place is literally the "capital."

Unique ingenuity in expressing kanji

When I am asked to write a manuscript for a post in Japan, the first question I am usually asked is, "What is a colony?"

In Brazil, the Japanese immigrant settlements have long been referred to as "colonies." This term also tends to be taken as an imperialistic one in Japan, and so it must be treated with great care. In particular, when it is described as a "colony of Japanese immigrants," it seems to be misunderstood as some kind of imperialistic invasion.

From our perspective, it is an idiom that has been used since before the war, and is also included in proper nouns such as "Hirano Colony," so we have no choice but to use it.

As it is an ancient colonial language, it has many expressions such as "settlement" (entering a colony), "coming to a colony" (coming to a colony), "staying" (while staying in a colony), "returning" (returning to a colony), and "leaving" (leaving a colony). It also had the expression "full settlement" (when the colony's plots of farmland are sold out and filled with settlers).

Since most immigrants before the war were agricultural workers, there are many colonial words related to agriculture. Large plantations are expressed as "farmland," leading to words such as "entering the farm," "leaving the farm," and "leaving the farmland in the middle of a contract."

Although it is rarely used nowadays, it once meant "fire wine" (high-alcohol distilled liquor, such as shochu) or, locally, pinga (a distilled liquor made from sugar cane).

The unit of area was written as "area" and pronounced "arkaire" (2.4 hectares).

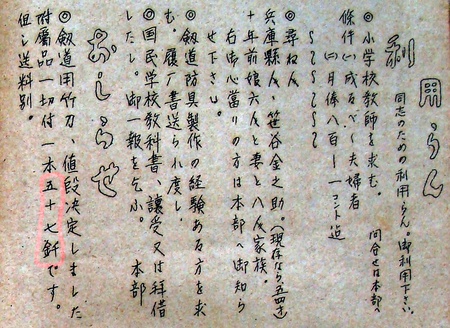

The unit of currency was the 釬. In Japan, it is pronounced "kan," but in Japanese society, it is pronounced "mir" (meaning 1000). Since "mir" is a combination of the "kin" radical and the "sen" radical, I'm impressed by how well thought out the unit was.

How to express katakana

Katakana was originally used to pronounce foreign words in Japanese. Until the Edo period, words were borrowed from Chinese, such as the Analects of Confucius, to broaden the scope of the Japanese language.

The few exceptions are Portuguese words brought over by missionaries such as Francis Xavier. There are Portuguese words that we use casually, such as "castela" (meaning "castle" in Portuguese), "karuta" (meaning "card"), "tempura" (originally "tempero" meaning "flavor"), "kappa" (rain gear), and "biyombo" (folding screen).

After the war, most of these katakana words became English. In Brazil, which is completely different from the Japanese situation, the katakana of Colonia became Portuguese.

For example, when it comes to the word "Christmas," "Natau" fits better in Japanese newspapers.

"Handle" or "Volante"? "Forward" or "Atacante" in a soccer match? An extreme example is a mix of English and Portuguese, such as "Cake cutting" or "Bolo cutting".

One example of a "mixed usage" that I found to be a wonderful expression is the phrase "Na Hora (on the spot) to become a tsuka." It has a nice ring to it and a modern feel to it that stuck in my mind.

Because most Japanese katakana is English, if a Japanese newspaper were to publish it as is, readers would complain. Just recently, I received phone calls asking questions like, "What is a legacy?" and "What about NGOs?"

I've been living mainly in Brazil since 1992, so I'm not good with words that were created in Japan after that. I didn't understand AKB at first, and words like "ara-sa" and "ara-fo" didn't make sense to me. Even now, when I talk to people who have just come from Japan or expatriates, I sometimes hear katakana that I don't understand.

Readers of Japanese language newspapers continue to treasure the Japanese language of 50 or 60 years ago when they left Japan. As a result, the articles distributed by Kyodo News are written in Japanese, but the parts edited by Nikkei Shimbun independently are strangely free of English katakana.

© 2017 Masayuki Fukasawa