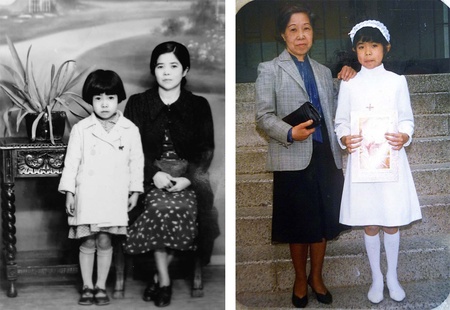

I spent almost all of my childhood with my grandmother. Her customs, which were of course very Japanese, were reflected in her daily life. She didn't celebrate Christmas, but she did celebrate Oshogatsu (New Year in Japanese).

In those days, I remember that preparations for Oshogatsu began on December 31. Starting at dawn, we cleaned the house, while my mother cooked. She spent the entire morning cooking tofu, a pork dish with turnips and carrots, kombu knots, plenty of sushi and even sweet potato and vegetable tempura. All of this food was prepared as an offering for the butsudan (Buddhist altar) in our home and shared with the family for Oshogatsu.

We bid farewell to the 31st by going to bed early. The next day, Oshogatsu began. Going downstairs to the dining room, the first thing we saw was a pitcher full of wakamizu. My grandmother had filled a pitcher with tap water. She believed that drinking a glass of tap water on Oshogatsu would bring good health throughout the year. The wakamizu couldn't be made from boiled or bottled water; it had to be the first drops of the first day of the year, taken directly from the tap. "This the elixir of youth," she told as as we drank it.

There were times that I didn't understand why we did this or that to commemorate the New Year, but we still continued those customs at home. “In my day…”, I recall my grandmother saying about her customs, the same ones she brought with her to Peru more than a century ago. But the time hasn't passed in vain. Nikkei still celebrate Oshogatsu, but in our own way. Some celebrate with a more Peruvian touch while others adhere closely to Japanese customs.

To write this article, I asked several people, "What do you remember about Oshogatsu? Many talked about their childhood. It was like traveling to the past, listening to memories from people of all ages and different periods of time.

PRE-WAR MEMORIES: MOCHI

"I remember making mochi at home," says Itzue Murakami, an 88-year-old Nisei who spent her childhood on the San Nicolás plantation. "My father mashed the rice with the kine (wooden mallet) while my mother used her hand, with a little bit of water, to turn the dough. It was a lot of fun watching them make mochi." Itzue has fond memories of her childhood. Her parents prepared so much mochi that there was enough to eat even after Oshogatsu. "We toasted it in a pan with a little bit of oil," she explains.

That was the pre-war period. Life revolved around work and the first Issei had little time to spend with family. Whether in the country or the city, they were forced to adapt their customs. Many Issei worked on plantations while others had their own businesses in town. Although many people worked on December 31, in one way or another they all celebrated Omisoka (New Year's Eve).

Preparations began with cleaning the house; this traditional cleaning (osoji) was very thorough, and included throwing out anything that was old or broken. Everything had to be ready for Oshogatsu.

FOOD BRINGS A FAMILY TOGETHER

Families worked hard to prepare a special dinner and food for the next day, which was Oshogatsu. Dinner on December 31 always included toshikoshi soba, a soup with long soba noodles that represent long life. If soba noodles weren't available, similar noodles could be subsituted.

On Oshogatsu, no one worked or cooked. All of the food was made the previous day so time could be spent with family. In the afternoon, everyone went out to visit relatives and share New Year greetings.

"When we lived on the San Nicolás plantation, my mother prepared ozoni for the New Year. She made a broth and added kombu, kamaboko, shiitake mushrooms, turnips, carrots and plenty of chicken. And finally, mochi," Itzue remembers. Like the ozoni for breakfast, they also prepared onishime (vegetable dish) and sekihan (rice with azuki beans) for lunch.

Strong believers in the spiritual world, the Issei placed offerings to the kamisama (gods) and to the dead, asking for better fortune in the New Year. The osonae (mochi offering), lighted candles and even an entire salary or the wages from the day were placed on the altar in the hope that they would bring prosperity, well-being and better earnings in the New Year.

AFTER THE WAR, LIFE GOES ON

After the war, the Issei continued to celebrate Oshogatsu, but some of the preparation began to take place outside the home.

Many Issei had their own businesses and sales increased around Christmas and the New Year. Few had time to make mochi at home; most preferred to buy it from the Japanese candy shops of the day, such as Kotobuki in downtown Lima and Tsukayama in Capón Street. But onishime and sekihan were still essential dishes at Oshogatsu.

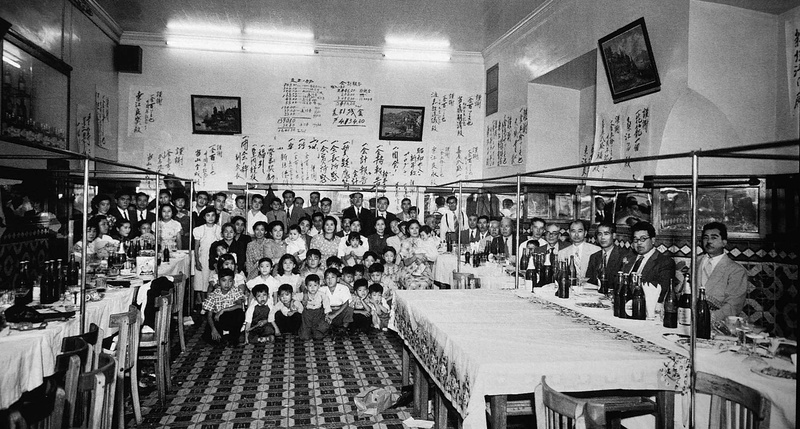

In those years, the Japanese community had ideal spaces for celebrations. But still reflecting some modesty, they continued to celebrate Oshogatsu at home with the family.

Kazue Yabiku de Kohatsu, a well-known devotee of Okinawan dance in Peru, remembers one of these places in particular. "My father was the owner of Jardín Ancash. That's where the community celebrated weddings and birthdays. There were no Oshogatsu parties. Instead, on New Year's Eve we closed Jardín Ancash so we could clean (osoji) and celebrate the New Year with the family."

The 1960s: OSHOGATSU “A-GO-GO”

By the 1960s, local customs for celebrating the New Year had all but erased the traditional Oshogatsu. Young Nikkei maintained some of the Japanese customs of their parents, but not with the same intensity.

Dinner was still a family affair. But many young people went out dancing before midnight. Huge New Year's Eve parties were all the rage among the Nikkei. This was the 1960s and 1970s, a time when orchestras like Fresa Nesei, Caramelo de Menta, Seventy Seven and Blue Star livened up the end-of-year parties.

And who doesn't remember the Majestic? Almost half of the Nikkei community danced there, according to husband and wife Masami and Julia Kamiyama. The Majestic was one of best-known, emblematic dance halls in the Pueblo Libre district. Other venues frequented by Nikkei were La Bomba, run by the firefighters of Callao, and La Victoria school in Manco Cápac.

New Year's Eve parties at the Majestic began before midnight and ended the next morning. Its huge ballroom hosted hundreds of dancers. But the boom of the Majestic New Year's Eve parties began to decline in the 1980s. Since then, Estadio La Unión and the Okinawan Association of Peru have been the places where Nikkei prefer to celebrate the New Year.

Compared to the tranquility of the Oshogatsu of the Issei, the new generation was accustomed to ringing in the New Year with merriment and noise. Besides the dances, another typical memory of Oshogatsu are the firecrackers. Mr. Masami remembers his childhood in Barrios Altos, in the 1960s. "People went crazy with firecrackers on the 31st. I remember that everything was covered in red on January 1. There were red firecrackers everywhere, on the streets and rooftops. Some hadn't exploded yet and were like new. I went out to look for them and if I was lucky, I filled my pockets with unexploded fireworks lying on the ground."

But the parties were followed by calm. On the day after, Oshogatsu, Japanese customs became important once again, especially among the older people. They continued to visit relatives on that day, always bringing along gifts.

These gifts usually consisted of a tin of green or jasmine tea, canned peaches or fruit cocktail, a packet of somen (noodles), seasoning, crackers and osenko (incense), all carefullly wrapped. Families with a butsudan placed these gifts as offerings on the altar before opening them. And in some families, the children of the house received money in an envelope (otoshidama).

Today, very little has changed. Many of us continue to visit our families at the New Year, bringing a gift and placing osenko on the butsudan for Oshogatsu.

OSHOGATSU TODAY: BONENKAI AND SHINNENKAI

Over time, Oshogatsu celebrations moved outside the family home. These days, Nikkei organizations host fellowship meetings to bid farewell to the old year (Bonenkai) and ring in the New Year (Shinnenkai).

In December, the kenjinkai, clubs and other institutions usually organize the Bonenkai. They say goodbye to the old year with a special ritual of gratitude and recognition of the work of the institution's members. There are always performances as well as delicious food and a toast to a better year.

At the beginning of the New Year, Nikkei organizations celebrate the Shinnenkai. This celebration is an opportunity to remember important events that occurred over the past year and pay homage to members who will celebrate their birthdays in the new year, according to the Chinese zodiac.

Mochi, a symbol of long life and prosperity, is always present at Shinnenkai. The Peruvian-Japanese Association, an institution that represents the Nikkei community, also includes the traditional decorated Kagami Mochi and the Mochitsuki ceremony.

People still celebrate the New Year at home, but with more local customs. Many host New Year dinners, similar to Christmas. But dance parties are still preferred by many Nikkei to greet the New Year. And of course there are always good luck charms such as an abundance of yellow, or champagne and grapes.

Regardless of how we celebrate, we always look forward to a new and better year.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Itzue Murakami, Kazue Yabiku de Kohatsu, and Masami and Julia Kamiyama. SOURCE: Mary Fukumoto, Hacia un nuevo sol (Lima, 1997).

* Publication of this article is supported by an agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (Asociación Peruano Japonesa, APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. This article was originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 107 and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2016 Texto y fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa