The hundreds of thousands of Japanese immigrants who came to the Americas brought only the bare necessities: some clothing, perhaps a few photographs to remind them of home. But they also came with many traditions and customs passed down through their families in their home villages. Despite being separated from their birthplace by thousands of miles, the colors, flavors, and fragrance of food and celebrations on special occasions were unforgettable memories, etched in their minds.

The New Year celebration, shōgatsu, was undoubtedly one of the most important celebrations for the Japanese. To bid farewell to the previous year, on New Year’s Eve, known as ōmisoka, the family gathered together to enjoy special dishes and welcome the new year with both happiness and ceremony. This celebration, which in ancient times took place according to the Chinese calendar, began to be celebrated on January 1st starting in the Meiji era (1868–1912), when the Gregorian calendar was adopted (1873). This of course was the same day that New Year’s Eve is exuberantly celebrated in the Americas.

During the early decades of the 20th century, most of the immigrants were single men who began to form families and broader communities as they put down roots. At the same time, the New Year celebration was adopted by more Japanese, until it became a common part of Japanese life in America. This celebration was one way that immigrants could build cohesion and strengthen their bonds with one another.

Before World War II broke out, the Japanese communities dispersed in different states of the Mexican Republic—although not totally isolated from each other—organized themselves into regional associations. These seeds of organization enabled them to become more unified during the era of their “concentration” in the capital by the Mexican government during the war. They forged fraternal and friendship bonds and because of that, were able to collectively face the enormous challenges and adversity brought about by the war.

When Mexico entered the war in 1941, the forced concentration of Japanese immigrants and their descendants, ordered by the governments of many American countries, represented an enormous tragedy for immigrant families. In Mexico, the government forced them to move to Guadalajara and Mexico City in January 1942. Without financial resources, due to the confiscation of their property and sources of employment, the concentration in these large cities was the start of a new emigration.

The concentration also led to a greater achievement: the creation of numerous schools in the Mexico City neighborhoods where Japanese immigrants settled. Schools in Tacuba, Tacubaya, Contreras, and the city center ensured that not only did the children receive an education, but their parents participated collectively in the work of organizing the schools themselves. Because the families worked together and provided mutual support, the war ultimately benefited them by promoting stronger ties and community organization.

In the circumstances of war, was there anything to celebrate as 1942 came to an end? Groups of immigrants from different neighborhoods around the city understood that it was important to celebrate and to do so, they prepared a variety of dishes. One of these was Japanese noodles, toshikoshi soba, which roughly translates as “year-end noodles.”

But many other dishes were served in addition to soba. Perhaps the most popular was a large mug of chicken or fish broth known as ozouni, served with a piece of grilled mochi. Mochi is made from cooked rice, pounded with a wooden mallet until it becomes a paste that can be molded into different shapes. Families also ate this grilled rice paste with a sweet bean dish, oshiruko. Each dish had symbolic meaning; for example, eating noodles represented the desire for a long, healthy, and prosperous life.

However, the importance of the new year lay not only in the food that was prepared, but also the bonds forged among the families. To prepare the food, several days before New Year’s, even the women organized themselves in different neighborhoods to cook together. On the first day of the new year, the men visited friends in different parts of the city to express their gratitude for help provided throughout the year and wish them the best in the year to come. The children, decked out in their school uniforms, went to school that day to greet classmates and sing songs to commemorate the new year.

To host visitors bringing messages of gratitude and good wishes, the families also prepared food to share with them. These were occasions not only for eating traditional Japanese dishes, but also Mexican food they had learned to prepare in the various parts of the country where they had lived. This included Mexican tamales, made with corn flour and beef or chicken and topped with red or green sauce, as well as other typical dishes such as pozole (pork and hominy stew) or pancita (tripe soup).

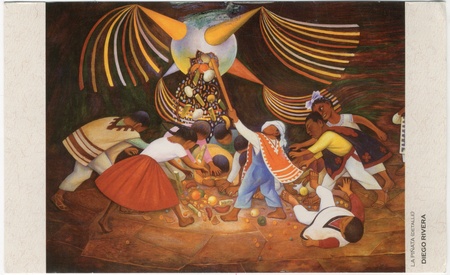

The New Year celebrations, therefore, combined both Mexican and Japanese cultural traditions. The Contreras district in southern Mexico City was home to a large group of immigrants and a new tradition: A family well-known for growing chrysanthemums, the Katagiri, served Mexican food to the visitors they hosted. The children were regaled with Mexican piñatas (clay pots gaily adorned with multicolor paper) which they broke open to find seasonal fruit such as sugar cane, tejocote (hawthorn), limes, and oranges, as well as candy.

Likewise, it is important to remember that the great majority of immigrants, once they arrived in Mexico, took on Spanish names in order to communicate better with the local population. As their families grew, the Japanese immigrants began to baptize their children and introduce them to the Catholic religion, without completely leaving aside their Buddhist and Shintoist beliefs. As part of the Catholic tradition, on Christmas Eve they attended the “misa de gallo” (rooster’s mass, also known as midnight mass) at Catholic churches to commemorate the birth of Jesus.

It is clear, then, that the festivities and traditions maintained by the immigrants and recreated in America, incorporating Mexican customs, created a kind of protective shield that enabled them, through celebration, to face the difficulties of war and persecution.

*I would like to thank Miyuki Sakai, Take Nakamura, René Tanaka, René Nakamura, and the Katagiri family for their help in writing this article.

© 2016 Sergio Hernández Galindo