It has been reported that the exclusionary immigration policies of President Trump have led to a sharp increase in immigrants and minorities in the United States who wish to emigrate to neighboring Canada. They say that they prefer Canada, which is more tolerant of immigrants than the United States.

However, after the start of the Pacific War, Canada implemented a strict segregation policy against Japanese people similar to that of the United States, or even more so. Japanese people living around Vancouver on the Pacific coast had their property confiscated and were forced to relocate to inland areas. Just like in the United States at the time, if they were Japanese people, their rights were stripped away, even if they were born in Canada and held Canadian citizenship.

In the United States, the internment camps were abolished around the time of the end of the war, and Japanese people were formally liberated and given their freedom. However, in Canada, they were not allowed to return to Vancouver for four years after the end of the war.

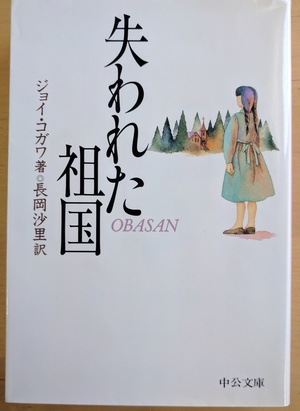

Joy Kogawa, a second-generation Japanese-Canadian woman writer, wrote a story about the difficult circumstances that Japanese-Canadian families found themselves in during and after the war in her novel Obasan. Published in 1981, it was highly acclaimed and won the Canadian First Novel Award, the Canadian Literature Prize, and the National Book Award.

In Japan, a translation by Nagaoka Sari titled "The Lost Homeland" was published by Futami Shobo in 1983, and in paperback form by Chuokoron-Shinsha in 1998. The original title, "Obasan," literally means "aunt," and perhaps the author intended to have the two characters who are the "aunts" of the protagonist symbolize the story, using this suggestive title even if it would be incomprehensible to English-speaking readers.

Based on Kogawa's own experiences, this novel is set against the backdrop of the path taken by Japanese Canadians during and after the war, and is a story about family told by the protagonist, Naomi, a third-generation Japanese Canadian. Before the war began, Naomi's mother went to Japan with her grandmother to visit her grandparents. Naomi never hears from her mother again. Meanwhile, her father is taken to a camp after the war begins.

Naomi and her brother Steven, who had been happy surrounded by relatives on their father's and mother's side, now live mainly with their paternal aunt Aya. Aya, who was born in Japan, was a quiet person who never got angry at discrimination or slander, and who devoted herself to others.

In contrast, her maternal aunt, Emily, is outraged by the injustice and cruelty of the policies that the government implemented against Japanese Canadians, and as a Canadian, she continues to campaign to make the government acknowledge its wrongdoings and to demand an apology and compensation even after the war. While her aunt Aya's words are "buried deep underground," her aunt Emily is a "warrior of words."

Both of them are carrying sadness, but the way they express it is in contrast. Naomi, caught between the two cultures symbolized by these two, touches the source of their anger and sadness. She especially looks at Auntie Aya's silent and helpless figure. However, while Naomi has respect and affection for all things Japanese, she also feels annoyance and sadness at the fact that she has always learned to be modest, endure, and persevere.

The story is divided into three parts. In the first part, 27 years after the war, Naomi reminisces about her childhood after the death of her uncle, Aunt Aya's husband. Why did her mother disappear? The question remains unanswered.

In the second part, the wartime diary written by Aunt Emily to Naomi's mother reveals the government's policies toward Japanese Americans at the time, as well as the reality of the slander and persecution they faced at the hands of the public and the media.

The Japanese were detained in horrible conditions and separated by gender, with one newspaper citing the reason as "to prevent the further proliferation of the (Japanese) race." Another newspaper headline stated, "They are a foul-smelling substance that enters the nostrils of Canadians."

Then, in the third part, titled "Letters from Nagasaki," the story takes an unexpected turn. In stark contrast to the psychological portrayal of the people close to Naomi through her eyes, the natural environment of her new home, and sometimes even a dream world, the truth about her mother is revealed, getting to the heart of the story, which had been somewhat hazy up until that point.

What comes through the story is respect for the first and second generation who survived under harsh conditions, family unity, and brotherly love, but needless to say, at its core is the violence of war and the distortion of the human heart that it causes, and the identities that are torn apart by war.

The author has Naomi reveal her heartbreaking thoughts about Japanese people who, even though they were born in Canada and are Canadian citizens, are still referred to as "Japanese people in this country" and sometimes asked, "When are you going to return to Japan?"

Where did we come from, in this bleak country? Oh Canada, whether you want to admit it or not, we were born here, in your bosom. We came from your soil, the mud, the swamps, the branches and roots. This is the country that uproots its people like weeds and throws them by the wayside.

Joy Kogawa was born in Vancouver to devout Christian Issei Japanese parents in 1935. During the war, she and her family were interned in a former mining town in the interior, and were later forced to relocate to another location.

After the war, he studied at the University of Alberta and the University of Toronto, and in 1992 wrote a sequel to Obasan, "Itsuka," which is set against the backdrop of the reparations movement. He also became active as a poet.

(Titles omitted)

© 2017 Ryusuke Kawai