Read Part 1 >>

Last year, I googled “Minoru Tamesa.” I can’t remember why. I was startled to find a picture of him as a young man, looking a bit like a “tough guy,” nothing like the quiet, prematurely aged, sensitive, almost fragile-looking man who came to dinner. Believing there might be few still alive who knew the middle-aged Min, I decided to share my memories of the man on Discover Nikkei’s Facebook page, hoping that others with more memories of him would come forward. Eventually, Ken Izutsu responded to my post with the following comment, edited slightly for this publication:

“My sister Karen and I both remember Min as a quiet, friendly man as well but we also remember his warm smile. Their peach farm was a magical place when the peaches were ripe; the colors and smells made quite the impression on both of us as kids. It seemed our life in Minidoka and after the war was lived in black and white, but our visit to the peach farm was in Technicolor. We both vividly remember Min and the orchard to this day. We also recently learned of Min's courage in legally challenging the government actions that denied us the fundamental freedoms guaranteed to all citizens by the Constitution. I guess this is another debt to the Nisei generation that we can never repay—we can only say ‘thank you’ for the countless sacrifices they made to secure a better life in America for their children. Unfortunately, too few Nisei survive to hear our thanks, but by remembering them and their acts of bravery in times of adversity, we keep alive the spirit and memory and sacrifices of our parents' Nisei generation.”

Ken’s name was very familiar to me. Reconnecting with him, I realized that he and my late husband were acquainted; they were contemporaries in academia, though in different fields and at different universities. Immediately after I heard from Ken, I received an offer to submit my recollections for possible publication on the Discover Nikkei website. Coincidentally, two of my second cousins came to visit me the next day. We had not seen one another for almost 50 years. We talked about Min and they remembered him very warmly and with great admiration. My cousins were eager to help me gather more information about him and his family. The Tamesas had been neighbors of my second cousins and lived across the road from the farm and nursery where they had grown up.

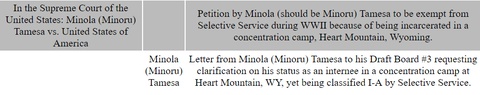

My cousins remembered seeing a copy of a letter written by Minoru Tamesa, which they believe was given to their mother, Marian Kurosu (who lived to almost 105 years of age) by Min’s father, Uhachi Tamesa. In this letter or other letters seen by my second cousin Lillian Sako (née Kurosu), Min explained his reasons for resisting the draft. It’s believed that Min would have agreed to being drafted if he were living as a free man at home. Foregoing a long and probably futile search for the letter in family attics and basements, I googled the subject instead and found a likely candidate for the long-lost letter referenced at the website of the Seattle Wing Luke Museum:

Now, I finally understood that Min was one of the Nisei leaders of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, and a hero. He was born in 1908 and would have been around 32 or 33 years old in 1943, when the cutoff age for draft eligibility was 35. I believe that Min’s letter is part of the trial records on his conviction on one of two felony charges. The first conviction was for resisting the draft; the second was for counseling others to do the same. All the Nisei Heart Mountain draft resisters were pardoned in a blanket pardon by President Truman issued at the end 1947. One of Min’s two felony convictions was overturned, and he was pardoned for the other felony conviction. The details of the two felony convictions, though important, are beyond the scope of this article. My writings here are personal memories of a warm, kind, brilliant man who took the blows for his beliefs with grace and dignity.

After a quick web search, I learned that even today, a reversal of a felony conviction and a presidential pardon do not always result in all records of the conviction being removed from the convicted party’s records. Clearing one’s name of an overturned felony conviction can be a time-consuming and expensive process.

In the family, we knew that Min had much more difficulty finding a job than the rest of those released from camp, although everyone had a hard time finding jobs amidst all the wartime anger and suspicion surrounding our release. I know my parents saw “No Jap Business Wanted Here” signs when they got out. I believe Min’s convictions were the reason for his added difficulty finding work.

The names of the draft resisters were well known; most Nisei and Issei shunned them. Between 20,000 and 26,000 Nisei were inducted or volunteered for military service during WWII. The 300 to 400 men who resisted the draft on the basis of the violation of their constitutional rights as citizens therefore represented a minority of minorities. The two sides had differing beliefs; each side paid a heavy price for their beliefs. However, everyone was motivated by their beliefs regarding the responsibilities and rights of American citizens; they all acted as patriots.

© 2017 Susan Yamamura