On the front page of the English section of the December 24, 2016, issue of The Rafu Shimpo, there was a small photograph of the emperor and empress of Japan. The caption read in part, “Emperor Akihito, accompanied by his wife Empress Michiko, waves to the crowd at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo on December 23, his 83rd birthday.” The Japanese American daily newspaper still deems the emperor’s birthday as newsworthy.

Until 1948 the reigning emperor’s birthday was a national holiday in Japan called Tenchōsetsu. Before the war, Tenchōsetsu was an important occasion in Nikkei communities as well. In the Imperial Valley, California, it was celebrated each year with picnics.

Like many European Americans who are fascinated by British royalty, I have always been fascinated by the history of Japan’s imperial family. So as I was planning a Nikkei exhibition called the Japanese American Gallery for the Imperial Valley Pioneers Museum, I was excited about displaying photographs of the Tenchōsetsu picnics. But I knew that it was a touchy subject and that I had to approach it with caution. Raising the subject of Tenchōsetsu could run the risk of perpetuating the misconception that Americans of Japanese ancestry are not truly American.

During the Second World War, a loyalty questionnaire was administered to all incarcerated Nikkei age seventeen and older. The most contentious questions were numbered 27 and 28. The latter read: “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?”

I added emphasis to the word “forswear” because it implies that both Issei and Nisei were loyal to the emperor as an inborn trait of their Japanese ethnicity. The last thing that I wanted to do by displaying Tenchōsetsu photographs was supply ammunition to those individuals who continue to believe that the mass “evacuation” and “internment” of the West Coast Nikkei population were justified.

Edward Tokeshi was a Nisei who had grown up in Brawley. I had the utmost respect for him. He was in Washington, D.C., for the 1987 United States Supreme Court hearing as one of the plaintiffs named in William Hohri’s class action lawsuit against the U.S. government for damages caused by Executive Order 9066. The lawsuit turned out to be a key component in realizing redress and reparations.

Ed advised me not to display anything at all about Tenchōsetsu; he said that we had come too far and it could set us back. This was in the early 1990s. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 had been signed into law only about three years earlier and the issuing of redress payments had just begun.

I was in a quandary. Whenever I needed guidance I always turned to the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles. I wanted to know how JANM was going to handle Tenchōsetsu. The national museum had not yet opened in the former Betsuin building of the Los Angeles Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple on the corner of First Street and Central Avenue. But in a warehouse on Vignes Street, I got to see a mockup of its inaugural exhibition Issei Pioneers: Hawaii and the Mainland, 1885–1924

Within the display, JANM intended to acknowledge that Tenchōsetsu was a controversial event, but because of the exhibition’s focus on the Issei generation’s early settlement years, it was able to limit the definition of Tenchōsetsu to the celebration of Emperor Meiji’s birthday on November 3.

Honoring Emperor Meiji was more innocuous. His reign began in 1868 and ended in 1912. Prior to World War II, US-Japan relations were probably at its best during the Meiji period. During most of that era mainstream society viewed Japan as America’s exotic little brother in the Orient.

My problem was not resolved because the photographs that I had were of Tenchōsetsu observances held in the Imperial Valley during the 1930s. Emperor Hirohito (Emperor Meiji’s grandson) ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne in 1926 and was the reigning sovereign then. Beginning in the early 1930s, Japan’s military unleashed atrocious aggression in Asia, and then waged war against the United States, all in the name of the emperor whom Nikkei communities celebrated.

Still wanting to include Tenchōsetsu in the Japanese American Gallery, I decided to display one photograph with the barest of captions. The caption merely stated, “Imperial Valley Tenchōsetsu Picnic.” There was no translation or interpretation. I reasoned that the photograph would conjure up fond memories for those visitors who enjoyed the picnics, while those who were not familiar with Tenchōsetsu would be none the wiser. It was intended to be a quick fix.

Over the years the original exhibits in the Japanese American Gallery have been enhanced with additional photographs, artifacts, and information. I am now at the point where I feel that the meaning of the Tenchōsetsu observance ought to be explained and put it into proper context.

I contend that Tenchōsetsu was a celebration of an ethnic community’s cultural heritage. And despite some seemingly jingoistic rituals involved, the picnics were in no way politicized rallies nor intended to incite Japanese nationalism. As former Brawley Nisei Tetsuro Patrick Sano remarked, “We attached no political significance to the fact that it was related to the emperor’s birthday.”

In the Imperial Valley two separate Tenchōsetsu picnics were held, one in the southend of the county organized by the El Centro Japanese Association, and the other organized by the Brawley Japanese Association in the northend. Patrick pointed out that a distinctive feature of the picnics was that they included the entire Nikkei community. “It wasn’t just for farmers, or merchants, or people from the same prefecture, it was for everybody.” He could have added that the picnics were attended by both Buddhists and Christians alike.

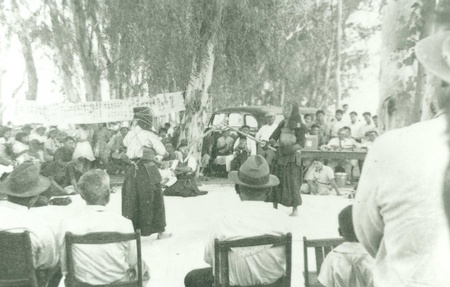

The northend picnics were held approximately three miles northwest of Brawley in a grove of eucalyptus trees near the New River. The men folk got there early and built a stage decorated with colorful streamers and flags, both Rising Suns and Stars and Stripes. A portrait of the emperor and empress was hung in a place of reverence.

U.S. flags were displayed and incorporated into the observance to show that the Issei chose the United States as their adopted country (even though they were ruled ineligible for naturalization), and that their children were American.

Nisei Boy Scouts directed traffic as the families all dressed up in their Sunday best began to arrive. A brief ceremony was held, which was officiated by the president of the Japanese Association. First was the presentation of colors – that is, the American flag – by Troop 10, Brawley’s all-Nisei Boy Scout troop. There were speeches and the Japanese Association president read what many Nisei youngsters mistakenly thought was a personal message sent by the reigning emperor, but in actuality it was an imperial rescript promulgated by Emperor Meiji some fifty years earlier. The ceremony culminated with everyone in attendance cheering three times in unison: Tennō Heika Banzai (Long Live His Imperial Majesty).

Then, according to Takeshi “Skip” Sato, “the fun began with entertainment, foot races for the young and old, martial arts demonstrations and sumo; with paper tablets, crayons, pencils, loose leaf binders, etc. as prizes for the children and useful household items like washtubs, buckets, mops, etc. for the parents.” The prizes were donated by local businesses, including stores owned by Hakujin (whites).

Each family brought its own bentō (box lunch), which the Issei women usually prepared the night before the picnic. Isamu “Sam” Nakamura recalled that his mother made musubi, teriyaki chicken, and kamaboko. Soft drinks were provided gratis by the Japanese Association.

Emperor Hirohito had been born on April 29, which meant that in the Imperial Valley Tenchōsetsu landed during the harvest season. In Brawley the annual picnic was held on the Sunday nearest his birthday. Sam was convinced that the picnic must have been organized by the Issei merchants in town, because Sunday was the busiest day of the week for truck farmers. They harvested as much of their crop as they could each Sunday for the crucial Monday morning wholesale market. Sam recounted how everyone in his family had to wake up extra early on the day of the Tenchōsetsu picnic and pick and pack tomatoes as fast as they could, then rush off to the picnic making it just in time to eat with everyone else. But Sam lamented, “We usually missed the contests and games.”

For the Nisei, Tenchōsetsu simply meant fun. The ceremony was something they had to sit through in order to get to the fun. The speeches and banzai cheers were their parents’ thing.

To the Issei – being products of the nascent universal education system of Meiji-era Japan – the emperors were exalted figures, not as political leaders but rather as symbols of Japan’s heritage. It would be wrong to think of the emperors as absolute rulers. According to Japanese mythology the first emperor, Jimmu, founded Japan’s imperial dynasty in 660 BC as the direct descendant of Amaterasu Ōmikami (the Sun Goddess). So in contrast to European monarchs who believed that they were sovereign by divine right, Japan’s emperors were believed to be demigods.

Because of their divine status emperors were supposed to remain, as historian Carol Gluck put it, “above the clouds” and not concern – or contaminate – themselves with secular matters, especially those as base as politics. Consequently, by the ninth century Japan’s emperors were molded into titular leaders whose value rested in their symbolic stature. Only one ambitious emperor, Go-Daigo (1288–1339), attempted to overthrow the governing shogunate. And for having the audacity to think that he could rule in his own right Emperor Go-Daigo was exiled to the Oki Islands in the Sea of Japan. The monarchy, however, was not abolished.

During the Meiji period the phrase “imperial line unbroken for ages eternal” was coined. As school children the Issei were taught that Japan’s monarchy was unique in that it was not only the world’s longest reigning hereditary dynasty, but also that the imperial family could produce the world’s oldest family tree. The emperor, therefore, is Japanese history and culture personified.

Celebrating Tenchōsetsu in America was the manifestation of the Issei generation’s pride in their unique heritage. It was a boost to their self-esteem given the racism they faced and the discriminatory laws enacted against them. It was not much different from other ethnic groups that countered oppression by celebrating their ethnic culture in such observances as St. Patrick’s Day, Cinco de Mayo, and Kwanzaa.

Because of World War II, Tenchōsetsu picnics came to an abrupt end and the historical importance of the occasion has largely been forgotten by most Japanese Americans.

© 2017 Tim Asamen