Nishi Honganji Los Angeles Betsuin, located in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, can be said to be the base of the Jodo Shinshu Nishi Honganjiha sect in Southern California. For over 45 years, this temple has been hosting a song show called the "American version of the Red and White Battle" in early January, attracting an audience of nearly 1,000 people every year.

Nishi Tuck (80 years old), a second-generation Japanese who has participated in planning and hosting the "American version of the Red and White Song Battle" since its inception, was born in the Sawtelle district of West Los Angeles and lived in Kaseda City, Kagoshima Prefecture (now Minamisatsuma City) from 1941 to 1956. Nishi's main occupation is gardening, and he started planning and hosting song shows after joining the Kotobuki-kai, a gathering of second-generation Japanese who were educated in Japan, at the West Los Angeles Buddhist Church (Sawtelle district) in the 1960s. In addition to his song show activities, Nishi has also served for many years as an officer of the Southern California Gardeners Association and the Southern California Kagoshima Prefectural Association, making him an indispensable figure in the Japanese community of Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, Gardena, adjacent to the south of Los Angeles, is known for its large Japanese population. The Gardena Buddhist Church in this city has an eight-tatami tea room, where Kayoko Inose (now 75 years old), a third-generation Japanese born in Long Beach, teaches tea ceremony once a week. Although she is a third-generation Japanese, her father was a second-generation Japanese who was educated in Japan, so she is fluent in Japanese and knows Japanese culture well.

Inose's youth was in the 1960s, and she spent a lot of time in the youth group of the Gardena Buddhist Church, where she met her husband, Kenichi, a third-generation Buddhist. Inose sold the family-run wholesale seedling business in 1986, and after retiring, she began taking on roles as executives for many Japanese-American organizations and began practicing the tea ceremony. She is currently one of the executives of the Urasenke Domonkai Los Angeles Association.

As can be seen from the examples of Nishi and Inose, many of the people who currently play leadership roles in the Japanese community in Los Angeles grew up or spent their youth in Buddhist churches in the city.

The author, who was interested in the role of Buddhist churches in Japanese communities, received an unexpected gift from Alan Kita, a long-time member of the Gardena Buddhist Church who also worked as an editor of the American Buddhist Church's newspaper at the San Francisco headquarters. I was introduced to Kita when I visited Inose's tea ceremony class at the Gardena Buddhist Church.

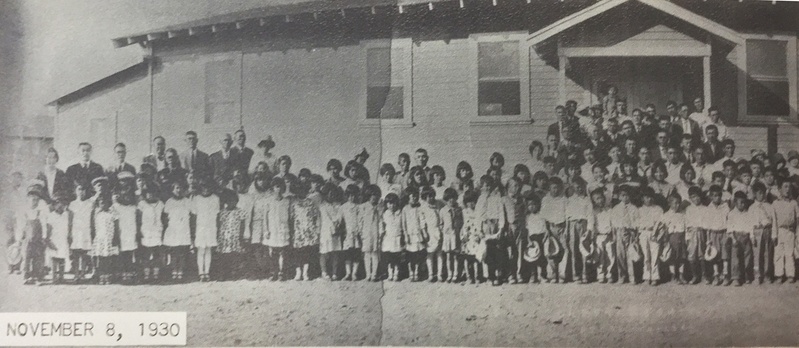

That very same day, Kita-san sent me a 100-page thesis. It was a master's thesis entitled "A Sociological Study of the Buddhist Churches in North America with a case study of Gardena, California, Congregation," submitted to the Department of Sociology at the University of Southern California on September 28, 1932 by Rev. Kosei Ogura, the first missionary of the Gardena Buddhist Church, which was established in 1931.

It was written based on data on Buddhist church activities collected in 1930, and clearly described the history of Jodo Shinshu missionary work in North America as well as the challenges and goals of the Buddhist church in the early 1930s.

First, Reverend Ogura explains the difference between Buddhist churches in North America and Japanese temples. This explanation is still useful for understanding the differences between Japan and the United States, even in the 21st century. A Japanese temple is built by a single monk and is passed down to his direct family. In contrast, Buddhist churches in North America are religious corporations recognized by each state, and buildings equivalent to temples are owned by the religious corporations, and monks receive allowances from the religious corporations.

The activities of the Jodo Shinshu Nishi Honganji sect in North America began with the founding of the San Francisco Buddhist Church in 1898. The Sacramento Buddhist Church was established in 1899, and the Fresno Buddhist Church in 1900. The Los Angeles Buddhist Church (now the Nishi Honganji Los Angeles Betsuin) was the ninth in North America, founded in 1905. In the same year, Buddhist churches were also established in Hanford, located in central California, and Vancouver, Canada.

The North American Buddhist Mission, the headquarters for missionary activities in North America, was established in San Francisco in May 1899. After World War II, the name of the organization changed to The Buddhist Church of America (abbreviated as BCA). The American Buddhist Mission has the authority to send missionaries to Buddhist churches around the country.

According to Ogura's paper, in 1930, there were 35 Nishi Honganji Buddhist churches in the western United States, including Denver, and only eight temples of other sects. In addition, it states that approximately 30,000 Japanese immigrants belonged to Buddhist churches in the early 1930s, and considering that the population of Japanese and second-generation immigrants interned in 1942 was approximately 110,000, this means that one in three Japanese immigrants at that time belonged to a Buddhist church. Since there were many single people in the Japanese community at that time, if we compare the number of families, one in two families may have been members of a Buddhist church.

Rev. Ogura cites the fact that two-thirds of the members of the Buddhist Association were already Buddhists in Japan, and that many of the immigrants came from prefectures with many Nishi Honganji temples, as reasons for the increase in the number of members of the Buddhist Association. He also reports that Japanese immigrants gathered at the Buddhist Association mainly for social reasons, not for religious reasons.

He also states that at the time, the missionary work of Jodo Shinshu to ordinary Americans had not progressed at all, and therefore the only possibility for Jodo Shinshu to survive in America was for second-generation Buddhists to continue attending Buddhist churches even after they became adults.

The children of Buddhist church members attended Sunday schools and Saturday and weekday Japanese language schools held by Buddhist churches in various regions. This was due to the parents' desire to teach their children Japanese, as well as the active efforts of the religious organizations, who believed that getting second-generation children interested in Buddhism was the only chance for the Buddhist churches to survive.

During the period of Japanese internment, all land and buildings owned by Japanese Americans were said to have been confiscated, but the Buddhist church building in the Los Angeles area during the war was protected by the Christian pastor Rev. Julius Goldwater. When Japanese Americans began to return home from the internment camps in August 1945, the Buddhist church building in Los Angeles began to serve not only as a temporary hotel but also as a community center, providing a place for the exchange of information and job placement.

In the case of the Gardena Buddhist Church, it was not until 1949 that it was finally able to resume its original role as a Buddhist church. In the 1960s, new Buddhist churches were established in several locations in Los Angeles, and Japanese American community centers were built in their neighboring areas, and the Buddhist churches and Japanese American communities reached their peak.

As in the examples of Nishi Tack and Inose Kayoko, mentioned earlier, there are many community leaders in their 70s and early 80s in the Japanese community of Los Angeles today who have been influenced by the Buddhist Church. This is because relationships within the Japanese community were formed through the activities of the Buddhist Church in the 1960s.

© 2017 Shigeharu Higashi