This should be read as a sequel to my previous article, "South America's Japanese Creole Language, Colonia ." This time, I've written mainly about the subtle writing styles of Colonia, which are related to "identity."

First of all, is "immigrant" a banned word on TV?

In the "Reporter's Eye" column of the June 4, 2004 edition of the Nikkei Shimbun, I wondered whether NHK had made the word "immigrant" a banned term and gave the company's response.

This is because I heard from Miyao Susumu (deceased), former director of the São Paulo Institute of Humanities, that when he was going to appear on a live NHK program, he was warned by a staff member at the company in advance, "Please do not use the word 'immigrant' as it gives the impression of abandoned people. Replace it with 'migrant.'"

How bland it would be if the word "immigrant" were to disappear from Japanese society... This is truly a question of language that is related to identity. Words like "Immigrant Day," "Amazon immigrants," and "100th anniversary of immigration" are important words that people are proud of and use to express themselves. If these words are to be included as "banned words" in major Japanese media, then the word "immigrant" itself would have become a colonial word.

When I inquired on the NHK website, a representative from Japan made an international phone call and explained, "It is not a word that should not be used. However, the program production staff may make a decision at the appropriate time." He then revealed the background to the situation. "Previously, when we used the word 'immigrant' in a program, we received a complaint that it was a word that hurts people who have immigrated. The opinion was that it should not be used because it has the nuance of 'abandoned people,'" the representative explained. He continued, "If South Americans use it with pride, then there is no problem at all. On the contrary, if there is a nuance of pride and it is the only word that can be used, then it is even more so."

I later checked with correspondents from Kyodo News and other agencies, and found that it was not a banned word and was actually being used.

So I thought about those who emigrated but were unsuccessful and returned to their home countries. It is estimated that there were 25,000 people who emigrated to Brazil after the war alone.

Among the returnees, there are a considerable number who had unpleasant experiences in Brazil, or who had a hard time starting over in Japan after being labeled as "returnees from Brazil." Therefore, there is a possibility that there are quite a few people who never want to hear the word "immigrant," which is directly linked to unpleasant memories, again. I speculated that the person who called NHK to complain might have been one of those people.

Those who consider their migration to be a success and those who regret it as a failure understand the word "immigration" with different nuances. Naturally, there are many people who consider their migration to Brazil a success, while the proportion of returnees who consider their migration to Japan a failure is overwhelmingly high. I cannot help but think that this situation is influencing the complaints against NHK.

The troubling expression "GAIJIN"

Needless to say, the word "gaijin" itself is fraught with subtle problems.

In terms of the meaning of the Japanese word in Japan, Japanese immigrants are the "gaijin" in Brazil. However, in the Japanese community, when "gaijin" is used in a setting where there are Japanese people of all generations, such as issei, nisei, and sansei, it means "non-Japanese." Incidentally, the debut film of third-generation Japanese-Brazilian film director Yamazaki Chizuka was "Gaijin, the Road to Freedom" (1979) (I confirmed the kanji for her name Chizuka when I interviewed her mother. Even she herself does not use the kanji, but Japanese-language newspapers use it out of respect for her parents' wishes).

In terms of the original meaning of the Japanese word, second-generation and third-generation Japanese people and non-Japanese people all have the same Brazilian nationality, so it would be strange for second-generation Japanese people to refer to non-Japanese people as "gaijin." However, when you look at how it is actually used, it is clearly used to mean "people outside the Japanese community." In other words, it has already deviated from the meaning of "gaijin" in Japanese.

In other words, the word "gaijin" itself has not changed, but what it refers to has changed, becoming a colonial word. What can be inferred from this is that, since the word "gaijin" is a Japanese word, it implicitly implies that people with Japanese blood are considered "relatives" or "inner citizens."

Believe it or not, there is a non-Japanese Brazilian who has taken advantage of this and started a band called "Gaijin Sentai." The sense of naming something that takes advantage of this subtle sensibility is incredible. Or rather, it's too amazing.

When I asked them about the origin of the band name, they emphasized that they knew the meaning behind it and decided to make a pun, saying, "We were originally a rock band, not anime or special effects. We're 'gaijin' because we come from a different genre, and also because there are a lot of Japanese people in the anime industry, so we're gaijin." The band (6 people) formed in 2004 and began performing mainly at anime events.

His repertoire consists of over 40 songs, mainly from special effects. He also has over 10 original songs. This "original song" is a mysterious world. I bought his self-produced CD "GAIJIN SENTAI Jaguachimen VS Sunrider" and listened to it, and found that he had made a special effects hero movie and recorded its theme song on the CD. I wonder how many maniacs there are in Japan who would go that far. The melody is heavy metal, and he sings meaningful lyrics in Japanese, such as "A foreigner who protects his own world! Who are you? But when darkness envelops us, we must be enlightened."

As for other uses of "GAIJIN," there are at least two supermarkets named "GAIJIN" run by Japanese Brazilians in the city of São Paulo alone. It seems that they originally thought of themselves as "Japonese" in Brazil, but when they went to Japan to work as dekasegi workers, Japanese people called them "GAIJIN," so they redefined themselves as "GAIJIN" and used it in the name of their stores.

Is "Kurombo" good or bad?

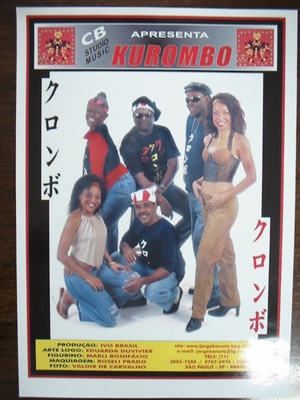

By the way, about 15 years ago there was a black samba band called "Kurombo," and I wondered whether it was okay to write an article about them as they were.

The band was formed by a group of Brazilian musicians who had previously been invited to Japan in the 1970s and 1980s and spent around six months performing in bars at night.

According to the men themselves, in Japan, promoters (who, it seems, were mostly Yakuza gangsters) would call them "Hey, Kurombo, Kurombo," so they thought "Kurombo" was the normal Japanese word for "black person." Incidentally, in Brazil, the hideaway villages that black slaves built after escaping from the farms are called "Quilombos," and since the word sounds a bit similar, it seems they felt a strange affinity with it.

If the black person himself understands the circumstances and chooses to use it, there is no need for people around to complain. It is the same as "GAIJIN", but it was a very difficult case to judge.

Another problematic Japanese expression that is becoming established in Brazilian society is "Hentai" (pervert).

These are so-called Japanese anime pornographic movies, but they are known as "Hentai" among young people in Brazil. It is unclear who first coined the term "Hentai" and when, but it was probably someone of Japanese descent.

It seems like a very apt expression, but it also feels a little off; it's still a bit of a tricky expression.

Is "dekasegi" a discriminatory term?

At symposiums on Brazilians working in Japan attended by Japanese scholars and others, I have heard several times the opinion that the word "dekasegi" is discriminatory and should not be used. As a result of this trend, some people in the Japanese community are of the opinion that "it is better not to use the word dekasegi."

To be honest, having lived in Brazil for over 20 years, I no longer understand the nuances of the words used in Japan. Out of respect for the words of researchers, I try not to use the word "deskasegi."

However, in Brazil, the word "Dekassegui" has already been adopted into Portuguese and is used in general newspapers, and there is no discriminatory nuance in it. Therefore, "Dekasegui" is used as a loanword from Portuguese.

I don't know if this is good or bad. However, I feel that discrimination will not disappear just by saying "Let's not use it because it is discriminatory." The topic is too serious, so I will not go into it here.

© 2017 Masayuki Fukasawa