In the early days at Manzanar, before most of the internees arrived, there weren’t many internees or military personnel in the camp trained in medicine. There may have been a couple of women who were nurses that arrived there first, but if someone got sick or injured in camp they had to improvise to help the sick and injured. Often there weren’t enough medical supplies or the right kind of supplies for the treatment.

Richard remembers a guy who had a severe toothache, but there wasn’t a dentist at the camp yet. The man was in excruciating pain and he was sick, probably from the tooth being infected. One evening they had to help him, so in the mess hall, after the last meal was served, they pulled his tooth with a pair of pliers and stuffed strips of cotton from a bed sheet in the cavity where the tooth was pulled to stop the bleeding. There was no painkiller for him during and after his tooth was extracted and he screamed, cried, and moaned during and after the procedure. Richard witnessed this horror being done to help the man. It was one of many disturbing conditions that Japanese Americans had to endure and witness while imprisoned.

Eventually, a crude hospital was built at Manzanar which was mostly staffed voluntarily by the Japanese American medical personnel who came to the camp to be interned. There was a doctor from the nearby town of Lone Pine that came to Manzanar to help from time-to-time.

Life at Manzanar in the first few months took a toll on everyone sent there, mentally and physically. Richard tried to remain hopeful that this unjust detention would be over soon, but days, weeks, and months dragged on into years. John Barrymore attempted to get the Nishimura family released under his care and responsibility, but Congress and the military denied his request.

Richard spent many monotonous days hanging out with other men from his block. They would find a fairly sheltered place like a large tree to hang out and talk and just pass the time which dragged on. Occasionally Richard joined the guys who would sneak out of the camp in the early morning to go fishing in the streams near camp. This, at least, helped add some fish to their diet of army rations being served in the mess hall.

There were a few violent incidents that occurred with the guards and military police that patrolled Manzanar. If MPs came upon a group of guys hanging out together, some of the hostile patrolmen would break up the groups and address the men and women as “prisoners.” Richard remembers one of his buddies, fed-up with the attitude of an MP, yelled back, “Don’t call us prisoners! We are Americans! We have names!”

For one thing, there was nothing much to do for the young men and women who had already graduated high school and didn’t have families of their own yet. Most everyone volunteered to do various work around the camp to make the best of what little was there and make the environment “livable.” But there was just a lot of free time that men and women alike had to fill and socializing in groups was natural for them to help each other cope emotionally.

There was no need for the guards and Military Police to be aggressive with the internees. Being harassed for just talking with friends was cruel and unjustified, the whole situation was unfair and harassment from guards added insult to injury.

In the beginning, meals in the mess halls were served on metal trays from the military and were terrible and caused everyone to have diarrhea. Richard remembers there were only beans being served for almost every meal, and then some Spam and some canned fruit were delivered. The food provided was surplus army rations that got sent to Manzanar. Soon rice was delivered but it wasn’t until Japanese took over the cooking that the rice was prepared properly. Later a small chicken ranch and a hog ranch were built at Manzanar and the internees took care of the livestock, did the butchering, and distributed the eggs. Some vegetables were grown in small plots around the various blocks of barracks. Richard remembers his mother cooking rice on the stove inside the barracks on cold winter mornings and would give her family hot bowls of rice with a raw egg on top. When mixed with the hot rice, the egg would cook. It was a filling breakfast and better than what they might get in the mess hall, but it was far from the variety, quantity, and quality of food the family had when they were home.

Most of Richard’s brothers and sisters adjusted to the camp life and formed close friendships with others of their age in the Manzanar School and families that lived in their block. His brother Donald was eleven-years-old at the time and found life at Manzanar was less isolated than life in Beverly Hills on the Barrymore estate. At home, he only had friends in school because he wasn’t allowed to make friends and play with the affluent children in the neighborhood. At Manzanar, he had many friends who were all equal in status and enjoyed the freedom to play with boys and girls his own age.

Richard’s father, grandfather, and uncle set out to create gardens around the camp to bring beauty and serenity, and to feel that they were keeping their craft of landscape artistry alive in such a harsh desert setting. Richard’s father and his uncle Ryozo Kado created more than gardens in Manzanar while they were interned. Uncle Kado, who was a skillful stone mason as well as a landscape artist, built the famous cemetery monument and he also built the stone sentry post building at the entrance of Manzanar. You can still see both of these structures and the remains of the gardens that Richard’s father, grandfather, and uncle built and created if you visit the Manzanar War Relocation Center.

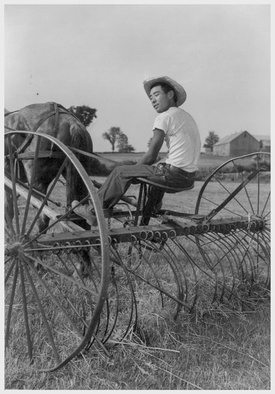

As the U.S. involvement in WWII grew and young men enlisted in the military to fight in the war, many farms across the country were left without enough laborers to plant, harvest, and attend to crops and livestock. Soon interned Japanese Americans were recruited to go to these farms and were paid a minuscule salary for the back breaking work they did.

Richard spent time in Idaho on a potato farm during harvest. He hoisted 50-pound sacks of potatoes lined up along the path between rows of potato plants onto a flatbed truck that slowly drove along the row. This is a very physically demanding job and it was even more challenging for Richard as he was not as tall as men who usually did this work. When they reached the end of the row, which was about a mile long, he would have a short break for water and then he would have to start the next row hoisting more sacks onto the next truck. For Richard, who was a young man from the city, this was a punishment from hell that seemed to go on forever. The bunkhouse for the farm workers was even less comfortable than at Manzanar and the food was on par with the dismal accommodations.

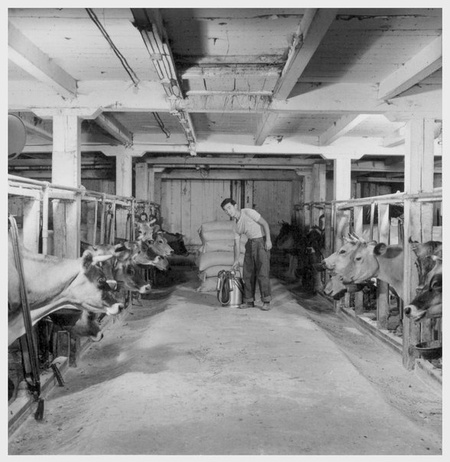

After the assignment was done he and the other Japanese workers were transported back to camp and they would be assigned to another farm job within a few days or weeks. Richard was apprehensive about future farm assignments, but he had better luck at a dairy farm in Vermont where he tended to the cows and did many other duties around the farm. It was still a demanding job, but it was much more pleasant than the potato harvesting. The family that owned the farm was very kind to him and he ate meals with the family often. He stayed in Vermont for a few months working at another farm that produced maple syrup. There he tapped the maple trees and collected the buckets of sap for processing. Richard also got assigned to work for a logging company and went out with crews into the forest to prepare cut trees to be trucked to the lumber mill.

All of the labor Richard did paid less than the normal rate so businesses and farmers who utilized these “prisoner” workers benefitted from the cheap labor. Richard and the others who went out to work did it to earn money so when they got released from the camps they would have a savings to start a life again. They received so little and no recognition, but all who volunteered to work did a valuable service for America by providing labor for the agriculture industry, helping the US economy remain strong and keep a variety of goods available for free American citizens to purchase and enjoy at an affordable price during wartime.

After returning to Manzanar from working the farms Richard enlisted in the Army. Hundreds of Japanese American men had already enlisted and many of them were in the highly honored and decorated 442nd army regiment. Richard Nishimura was tested when he enlisted in the army and due to his high scores he was assigned to the 441st army regiment in the CIC (Counter Intelligence Corps) and after boot camp, he went off to Fort Richie in Maryland to the Military Intelligence Training Center. By the time Richard completed boot camp training, Japan and the United States had signed the peace treaty and the war was over. Richard, a corporal in the US Army CIC, was deployed to Yokkaichi, Japan, to monitor suspicious individuals and groups that might disrupt the occupation, reform, and reconstruction of Japan by the US allied forces led by General Douglas MacArthur.

While Richard served in the US Army, the family was released from Manzanar and settled in Seabrook, New Jersey, where they were welcomed and offered jobs and housing. The racial climate was still extremely hostile toward Japanese in Los Angeles and since John Barrymore had passed away while they were in camp, they opted for the East Coast. When Richard completed his tour of duty with the Army, he joined the family in New Jersey.

Living in Seabrook was a temporary location for Richard, his parents, and most of his brothers and sisters. After a few years in New Jersey, Richard and the family prepared to move back to Los Angeles. The prejudice had died down and there was an opportunity to re-establish a landscape business for his father. Before moving back, Richard met and was dating Chiyeko Kuju, who he met at Seabrook Farms where they both worked. He asked Chiyeko to marry him and move to Los Angeles to begin a life and family together. She said yes and I was born in Los Angeles a few years after.

My mother passed away in 1968 due to complications from breast cancer. My father found love again and married Felisa Doroteo a few years later. Richard Nishimura had a successful career as a traffic manager, directing shipments for a respected fashion import company in downtown Los Angeles for many years. After retirement, he continued to work part-time as a bookkeeper for my Uncle’s Asian produce distribution company for several more years. He and my step-mom Felisa Nishimura both healthy and retired live happily and have a home in East Los Angeles. They continue to be a vital part my life and the Japanese and Filipino American communities.

* This article was originally published on the author's blog Nishis Niche on March 21, 2016.

© 2016 Karen Nishimura