“What are you working on now?” my hairdresser asks me. We’ve seen each other for years, and she knows about my writing projects.

“I’m working on an essay about Tacoma’s Japantown,” I say. She stops with the comb and scissors still in her hands. Pieces of my hair are already scattered on the floor. She looks puzzled, and I add quickly, “which doesn’t really exist anymore.”

“Oh, good, I’m glad you said that,” she says. “I was so confused. Because I wanted to know where it was. I’d like to go there.”

“Right? Me too,” I say.

* * * * *

I drive through Tacoma’s downtown frequently, at least a few times a week. I didn’t know for a long time that Tacoma had a Japantown. I moved to Tacoma from Seattle in 2004 and for more than ten years, I lived here before I found out about its Nikkei history.

* * * * *

A few years ago, I found a hand-drawn map of Tacoma’s Nihonmachi in Ronald Magden’s book Furusato: Tacoma-Pierce County Japanese 1888–1988. I thought about the buildings and businesses that I knew downtown. None of them, as far as I know, were owned by Japanese Americans. However, after searching through the notes and the bibliography, I couldn’t find out where the map came from. It was a mystery for years.

* * * * *

Just this year, I find out the map’s source. I’ve been commissioned by HistoryLink, the online Washington state encyclopedia, to write a history of Tacoma’s Nihonmachi. Tacoma historian Michael Sean Sullivan tells me that the map is from Kazuo Ito’s epic history, The Issei (Hyakunen Sakura, in the Japanese original edition). Michael’s been writing a few entries about Japantown on his local history blog. Ito was a Japanese journalist who had been hired by a Japanese American committee of business leaders to chronicle the stories of the Issei. It’s a magnificent compilation of oral histories, photographs, poetry, chronological timelines. It was finally translated into English in the 1970s.

I’m fortunate to borrow Michael’s copy of The Issei for my research. It’s a book that’s now out of print. It’s so hard to find that copies now cost at least several hundred dollars. It’s not in Tacoma’s public library collection, not even in the Northwest Room special collection focused on Northwest history.

* * * * *

Next I’m reading a hard-to-locate copy of The History of Japanese in Tacoma and Vicinity (Part I), written by published in 1917 by Shuichi Fukui and several co-authors, translated into English in 1988 by James Watanabe. (Parts II and III of the history are supposedly in the University of Washington’s Special Collections, but I haven’t found them yet.) Part of the book includes meeting minutes of the Tacoma Japanese Association.

I think I envisioned a more hardscrabble life, but looking over the minutes of the TJA—these Issei, they were organized. They raised funds together, held parties to welcome consuls, built their own Japanese language schools, churches, temples. When anti-miscegenation laws were hotly debated in California, moving to Washington, the Association hired a Caucasian lawyer to go to the state capitol and fight for the right to intermarry.

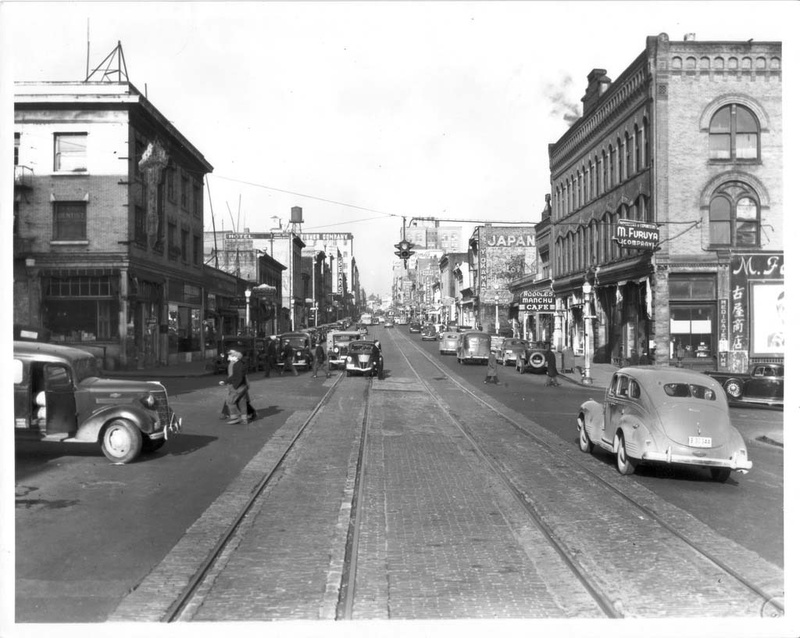

I discover that while reading this history even a simple directory can undo me. The “List of the Tacoma Japanese by Occupation” is nine pages long, single-spaced. There are fish markets and vegetable stands, Japanese and “Western style” restaurants, hotels, clothing shops, barber shops, laundries, grocery stores, art stores. Each entry has the name of the owner, where he was born in Japan, when he came to the Northwest, the names of his family members. And the addresses: 1342 Broadway. 1354 Market Street. 738 St. Helens Avenue. Each one of these entries represents a livelihood, a built life; together, over one hundred businesses strong, they represent a whole neighborhood.

I now have a different sense of what reparations might have meant to these Issei. How can you replace the soul of an entire neighborhood, entice the residents to return? (and in the face of anti-Japanese sentiment, less than 50 returned out of hundreds). Except for Gerard Tsutakawa’s beautiful Maru sculpture near Tacoma’s University of Washington campus, almost nothing physical downtown shows that a booming Japantown once existed in my city. I am writing because there is a gap in the larger stories we tell ourselves about Tacoma, in the larger stories about Washington State. There is no Japanese American neighborhood here now. And that is one of the many incalculable costs of the Nikkei wartime incarceration.

Maybe to some this will sound strange, but writing this history feels like conjuring a place into existence again just by writing about it. Maybe this is the magic of history writing.

* * * * *

A few tantalizing mentions here, three books that are somewhat difficult to find there. Books loaned from other mourners and rememberers of Tacoma’s Japanese history. A few precious photocopied newspaper clippings from the Tacoma Public Library. Oral history interviews and a few pictures in Densho’s archive, oral histories and research on Tacoma’s Nihongo gakko by the University of Washington in Tacoma. Archives of the Whitney Memorial Methodist Church, the Tacoma Japanese Language School, and the Tacoma Buddhist Temple. In some ways, a wealth of material—and I am lucky that so much of it is online!—but not much of it curated or indexed. There is a series of local history books about many neighborhoods in Tacoma, but not about Japantown specifically.

I’ve started to notice the publication history of my resources. The majority of them exist because of community organizations—like Discover Nikkei. Kazuo Ito’s book The Issei was funded in part by a committee of Seattle (which no longer exists). Ronald Magden’s Furusato, the history of Pierce County Japanese, was commissioned by a more recent Japanese American community committee. I am working in an established and proud tradition of ethnic media and ethnic studies: telling our stories because not many have and not many will. I am grateful and honored to be entrusted with this task.

But it’s also heartbreaking. During the research I have sometimes felt that I am not only speaking in a silence, but speaking against a silencing, an erasure. And so the writing is an act of mourning, a small act of healing, a small act of restitution.

* * * * *

“I’ve been in Tacoma my whole life,” says my hairdresser. “I was born in the mid 1960s. But I’ve never heard of a Japantown in Tacoma before. Where was it?”

I look around at the exposed brick walls of the salon. There are historic black-and-white pictures of Pacific Avenue on the walls of her room. The traffic noise of present-day Pacific Avenue is coming through the salon windows. The graceful dome of Union Station and the arches of the Washington State History Museum are just across the street.

“Here,” I say. “Actually, it was here.”

© 2016 Tamiko Nimura