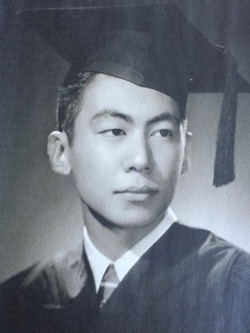

It’s unfathomable that the affable white-haired Nisei with the quiet laugh could ever be accused of being unpatriotic or cowardly. There’s nothing about this active 90-year-old, former Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) scientist with a Ph.D. in botanical science that could be construed as either weak or disloyal. On the contrary, Takashi (Tak) Hoshizaki, who signs everything with kokoro kara (a phrase that contains much more heart than its loose English translation of “sincerely” suggests), is a humble man who exudes nothing but warmth and integrity.

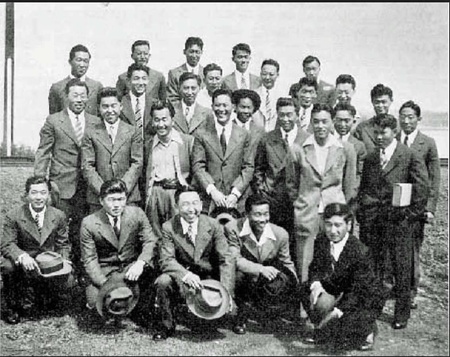

Even after spending nearly three years in a federal penitentiary, Hoshizaki holds no resentment or regret. One of sixty-three men at the Heart Mountain concentration camp who objected to being drafted as long as his civil rights were being denied and his family held in detention, he is perhaps one of only a few still alive to talk about what happened. Fortunately, Hoshizaki does not hesitate to speak out about his conviction and jail sentence. In fact, he has spent much of the last thirty years calling attention to those who resisted, even though his stance is still met with disapproval from some members of the Japanese American community. Proudly, he wears a t-shirt that spells out the principle to which he still avows, “No person should be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.”

The life-changing decision to become a Heart Mountain resister seemed almost effortless for the once young incarceree. It came after his first inkling of doubt at age 16 while still at the Pomona Assembly Center. He wrote to his homeroom teacher at Belmont High School expressing his concern about the legality of the incarceration and remembers all-too-well her response—she was “sorry” he was so angry. Two years would pass while he, his parents, brother, and four sisters were forcibly detained at Heart Mountain. The easygoing Hoshizaki would pass the time tinkering with model airplanes and working in the mess hall and camp engineering office. However, when called for his draft physical he quietly refused to go.

Hoshizaki documents what followed in a remarkable 63-page personal notebook that carefully, if not tersely and unemotionally, explains what happened from the moment he was picked up by the FBI on March 26, 1944, to the July 7, 1944 night before he was delivered to the federal prison facility at McNeil Island, Washington.1 His meticulously handwritten notes offer a rare day-by-day look into the mind of a young Nisei resister. Recounting what happened during those three short months, he describes being held in the county jail in Casper, Wyoming, and then transferred to Cheyenne for a two-week trial that culminated in a conviction of one count of draft evasion and a sentence of three years in federal prison.

His first entry illustrates Hoshizaki’s matter-of-fact style and pragmatic point of view. Filled with references to the clock, it also hints at what later became an important daily pattern, i.e., writing down what they were given to eat:

3-26-44. They got me at 5:00 [in the morning]. Took me down to Visitors Center. F.B.I. came and go me at 10:30. Arrived at Cody County Jail at 11:00. I met the rest of the group. F.B.I. then took us to the city jail and held us there. They just stuck us one at a time in the county jail and held us there. I didn’t eat today until 6:00. Miller didn’t give me time to get my toilet articles and didn’t let me eat. We were questioned by McMillian. Finger printed by “Red” Smith. Went to sleep at 12:00.

Three days later came the official departure from camp and more talk about food:

3-29-44. Awoke at 6:00. Packed and had breakfast at 6:30. Supposed to leave at 7:00 but left at 8:00. Went past Heart Mountain R.C. [Relocation Center] and went through Powell, Lowell, Worland and had lunch in Thermopolis. From there to Casper, arrived 4:00. Had a terrible lima bean soup. Couldn’t eat it. Went to sleep at 11:00. Got acquainted with 2 sailors (A.W.O.L.) in next cell.

The notebook is replete with almost daily mentions of what they were served: everything from hamburgers to stew, pancakes to potatoes, and macaroni to the occasional treat of steak. In the long wait for trial, eating apparently passed the time better than anything else, with the possible exception of playing cards. The subject is sometimes amusingly juxtaposed with more serious matters. For example, on 5-18-44, he wrote, “Red” Smith came over with a prisoner today. Last nite, the boys couldn’t get out on bond, but today they said it was ok. What a government. Well, we had stew today, it was cold....”

His account offers a look into the tedium of daily life in jail periodically interrupted by encounters with fellow inmates like prostitutes and drunken soldiers, as well as unpleasant bouts with bed bugs and lice. Everything is reported in the same flat and unemotional tone: “Today we had beans. Geo. Shimane found about one dozen lice on him. Several other fellows started to look for them and found some. We got some disinfectant and sprayed the whole joint. I didn’t find any lice on me yet....”

In far more graphic detail, fellow resister Yosh Kuromiya recalls in far more vivid detail this same period as being far more harrowing. According to Kuromiya’s account by law professor and historian Eric Muller, “Mattresses covered the floor of the corridor so densely that ‘you had to watch where walked when you wanted to get down the corridor to the shower.’ Opposite the cells and across the corridor was a long barred wall that made a cage of the entire unit. Twice a day the guards would shove ‘barely edible’ meals through the bars for the young men to each off of steel shelves in the corridor. ‘Most of the stuff they fed us,’ though, ‘went down the toilet.’”2

In contrast, Hoshizaki’s entries are brief but telling for the pressure he perhaps suppressed. For example, the 4-27-44 entry reads, “We had a full meal today. About 7:00 a bunch of soldiers marched by our jail. About 300 to 400 soldiers in all. This morning, the other fellows said that I talked in my sleep.” The following day, Hoshizaki wrote, “We had macaroni for dinner. Today, I received a package from home and also a letter from Harry Oshiro. We talked about Ben Kuroki [the celebrated Nisei war hero] and Sim said that his girl wrote and said Kuroki called us fools.” No comment from Hoshizaki followed.

With characteristic Japanese gaman (endurance or perseverance), Hoshizaki held his ground while at the same time holding onto the hope they would ultimately be vindicated by the judicial process. Commencing on 5-31-44, Hoshizaki ended each short daily entry with the remaining number of days to trial. The countdown evokes both the dreary tedium and anxious anticipation of their wait. “Only 11 more days,” “10 more days,” “9 more days,” “only 8 more days,” etc., and finally on 6-11-44, “We are all high in spirit. We sang songs. I wonder what it’s going to be tomorrow.”

The most spirited entries come during the infamous trial pitting Judge T. Blake Kennedy, who Muller characterizes as “racist, an anti-Semite and a xenophobe,” and U.S. Attorney Carl Sackett against the resisters’ skilled Denver civil rights attorney Samuel Menin.3 According to Hoshizaki, “The D.A. and Mennin argued like hell. Once in a while, Judge Kennedy would up and tell [off] both Mennin and the D.A....At the end of the trial, Mennin and the D.A. almost had a tangle.” On 6-27-44, Hoshizaki seemed to finally express what he was thinking: “Today we went to the courtroom at 1:45. Got our 3-year sentence at 2:30. Judge Kennedy assumed that the evacuation and detention is constitutional. I think he’s nuts. Anyhow we are going to appeal our case.”

In recounting the years following the conviction and nearly three-year imprisonment, Hoshizaki is ever optimistic. Pardoned with the rest of the Japanese American draft evaders by President Truman four years after their conviction, he was one of six Heart Mountain resisters young enough to be drafted again. With his civil rights restored, he unhesitatingly complied and served during the Korean War in the chemical biological warfare unit and as a lab technician in a station hospital in Texas. In his way of always looking on the bright side, he says he was fortunate to have landed these non-combatant roles because of his science study at UCLA, which department he suspected was somehow connected to the military effort.

Still vibrant and living on his own, Hoshizaki seems content in his longtime Los Angeles home that borders the ethnically diverse areas of East Hollywood, Los Feliz, and Little Armenia, and located only a block away from the grocery store established by his father in 1932. In a house filled with books, travel souvenirs, and scientific papers lovingly collected in past years with his late wife, Barbara Joe, he spends his time volunteering for causes that are important to him. As a board member of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, he makes regular trips to the former concentration camp to ensure this shameful period in American history is remembered, and he continues to fight for acknowledgement of the 63 men once labeled disloyal. As Hoshizaki puts it, “We were written out of Japanese American history, our story of draft resistance to regain our civil rights buried and forgotten.” In his own quiet, steadfast way, he continues to be the heart and voice of the ongoing struggle to preserve the American ideals of liberty and justice for all.

Notes:

1. The original manuscript can be found at the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center in Powell, Wyoming.

2. Eric Muller, Free to Die for Their Country (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001), 101.

3. Muller, ibid, 104.

* * * * *

Memories of Five Nisei

Japanese American National Museum

September 24, 2016 at 2 p.m.

Five second-generation Japanese Americans will share significant memories of their lives, with a focus on the World War II camp experience. The Nisei speakers, who are all in their 80s and 90s, will also compare their camp experiences with the present-day detention centers in Texas for Central American refugees.

Dr. Takashi Hoshizaki will be one of the panelists for this program. This program is free, but RSVPs are recommended. For more information >>

© 2016 Sharon Yamato