Alicia’s sister, Josefa (Sizue) Yoshimura, was two years younger, and had two “boyfriends” (the title changes depending on which sister of hers is asked). The first was named Octavio. He was in love with Josefa, but she didn’t consider him a boyfriend by any measure. Octavio was skinny and always wore a guayabera, a typical Cuban shirt that usually had stitched flower or patterned designs running vertically on each half of the front side. They are still popular in Cuba today. The second “boyfriend” was Margarito. He was overweight and more in love with Josefa than she was with him. In fact, Josefa didn’t like him at all, her friends and sisters liked to poke fun at Josefa by calling Margarito her boyfriend. She didn’t find the same humor in the joke that everyone else did.

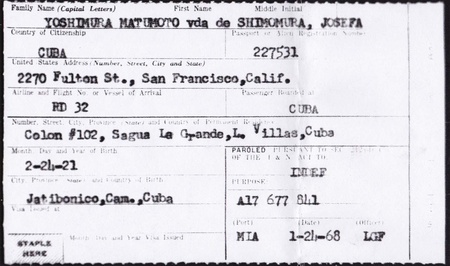

Josefa was born on July 17, 1921, but her registered birthday is February 24, 1921. Many Cubans during this time had two birthdays, a real one, and the one registered with the state. Josefa was not born in a hospital, but rather in her father’s home with him doing the actual delivery. Papa Abuelo was not a medical doctor, nor did he have any formal education or training to deliver children. Somehow he tapped into his paternal instinct and delivered all six of his daughters on his own.

Newborns were supposed to be registered in Havana by the family, not the hospital, and it was often difficult to make the trip there from Jatibonico, a long tractor ride being a common option. Officially registering your child’s birth was often not a high priority. There was supposed to be a fine for registering a child beyond a certain date after birth.

Josefa’s husband, Teiji Shimomura, would send his lawyer to handle the registration, but the lawyer was often sent late because Teiji was too busy. The lawyer had some connections with the government and basically when he was asked what date to register the newborn on, the lawyer would just say whatever date was available, which explains the haphazard nature of the family’s actual registered birthdates.

Josefa was the second of the six girls, born in Jatibonico Central where she was schooled through elementary school. None of the girls went past the sixth grade as they lived out in the country living a typical agrarian life. Josefa had a number of good friends, Cuban and Japanese alike. Amongst the Japanese Cubans, Mirta Suguimoto, Pilar Sakata, and Rosario Sakata were her best friends. These three never left Cuba as she did. Josefa still receives the occasional letter from Mirta Suguimoto. All three are still alive and doing well.

Mirta lives in a town called Taguasco which is about a twenty minute car ride from Jatibonico. She and her Cuban husband live in a decent sized house. Her 50 year-old General Electric refrigerator just got replaced by a new LG one, one of the recent social programs enacted by Fidel Castro, prior to his illness. Pilar and Rosario Sakata live in Jatibonico where Rosario’s daughter, Maria Pilar Moreno Sakata is married to Alfredo Enrique Rios and has two children. Josefa’s Cuban friends were Roselia Balmaseda and Blanca Cepero. Roselia lives in a suburb of Havana and is alive and well. Josefa felt that there was not a lot of racism in Cuba against the Japanese.

Josefa and Teiji (went by the nicknames Juan and Simon, the latter because Shimomura was too hard to say) lived in the countryside. Teiji worked as a capataz (a foreman) on someone else’s farm. And like most Japanese Cubans, they ate both Japanese and Cuban food, but more of the latter.

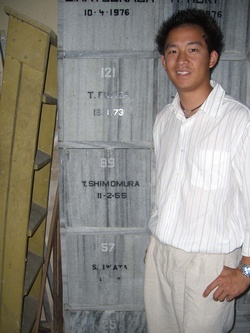

Teiji and Josefa had two children, Magaly and Luis Shimomura. When Magaly was three years old and Luis was eight months of age, Teiji died in a terrible accident. He was driving a tractor down a designated dirt road when it rolled over into a ditch. He got pinned underneath the tractor and he fortunately had a helper who freed him. The tractor was being taken back to the farm since the brakes were faulty, sadly enough the faulty brakes are what contributed to Teiji’s accident. He did not die immediately, in fact he walked away from the accident. He went to a clinic later where he hemorrhaged to death from internal bleeding. The accident occurred around 9:30 p.m. and he died around 1 or 2 a.m. After his death, Josefa and the children moved to Sagua la Grande to live with her father Hanjiro.

Luis does not remember his father, but he remembers a lot of his time in Cuba, before coming to the United States at age twelve. His first memory is living in Sagua la Grande where the family made and sold ice cream from a very popular store called La Japonesa. Ice cream was sold out of a storefront and from street carts.

Luisa, Alicia, Mario, Nancy, and Hector all lived in Sagua as well. They had a 19-inch black and white television, considered a luxury just as it was in the United States in the late 1950s. Luis remembers watching Zorro, The Lone Ranger, and professional wrestling on TV with his friends and family. They were the only Japanese family in town.

He remembers the family had hired two Japanese workers as well as a handful of Cubans. La Japonesa’s ice cream was some of the best in town, the most popular flavors were orange pineapple, chocolate, and coconut.

Luis, his sister Magaly, and his mother Josefa lived in a house that holds a special place in family history.1 Luis remembers that Castro wanted all Cubans to change dollars to pesos but Papa Abuelo did not want to as he distrusted the Castro government. So Papa Abuelo opened up a hole in the wall of the house and put bills and valuables inside and covered it up. A second hiding place was in the backyard where he dug a hole and buried mostly coins. There was a fear that you worked so hard for your money (in dollars) and that changing it to Cuban pesos might not be a good idea since the peso was weak at the time.

Regarding money hidden in the house, this is what is known. After the family fled Cuba in 1966, another family moved in immediately. They had no idea that there was anything of value hidden or buried on the property. A few years went by, and during a huge rain storm, the false roof was leaking and had to be replaced. Upon tearing down the false roof, the family found a large amount of silver in various forms. They immediately brought it to a place to sell the silver and it is thought that they purchased a television with the money. It is comforting to know that someone found the money and put it to good use.

Hisae (Ramona) Yoshimura was born October 30, 1923. The fourth daughter of Hanjiro and Tsuma. Ramona dreamed of being a school teacher, but those dreams were shattered when WWII broke out and Hanjiro was sent to a Cuban internment camp where all Japanese men in Cuba were detained at the behest of the U.S. government. Women and children were spared and were left behind to take care of the farm and/or businesses. At the conclusion of WWII, Cuba released all the Japanese, and Ramona married a man named Chutaro Ohashi. They had a daughter, Hiroko (Norma).

Yoshie (Aurora) Yoshimura was the fourth sister born March 21, 1926 in Jatibonico. When she was young, she loved to cook and ride her bike. She had chores to do such as cleaning the house and shopping for groceries and other items. Aurora was in public school till the age of 13 or 14 just like her older sisters. She didn’t really go out for fun, nor did she enjoy listening to the novelas on the radio, but Aurora did like to play card games.

Aurora learned to cook, and learned to cook well. As with many Japanese Cubans, she cooked traditional Cuban dishes such as lechon asado (suckling pig), arroz blanco (white rice), trout, pargo (red snapper), atún (tuna), arroz con pollo (chicken with Rice), bistec empanizado (breaded steak), picadillo (ground beef dish), and congri (a unique mix of white rice and black beans) among other Cuban dishes. She also cooked and ate some Japanese food, notably udon noodles. The udon was made by hand from scratch and was one Japanese item the family enjoyed on a semi-regular basis. There so was no sushi available due to the lack of Japanese food stores. However, sashimi (sliced raw fish) was prepared every so often although it was not very popular in the family since most of them were born in Cuba.

Like many other Japanese Cubans, Aurora had strong memories of celebrating New Year’s at the Japanese Ambassador’s residence in La Havana, the capitol of Cuba. She only went once, but there were 200-300 people and all the food and drinks were free. She did not drink any alcoholic beverages, she enjoyed Coca-Cola, Cawi lemon soda, batidos (milkshakes), and Materva (a type of carbonated drink from a root) which is her favorite drink to this day.

Aurora married a man named Raikichi (Bonifacio—but went by Boni) Tsuchiya on December 19, 1953 in Jatibonico, Cuba. Bonifacio was originally from Gifu, Japan. He met Aurora in a very roundabout way. One of Boni’s friends was going to introduce him to a single girl and while he was on his way to her house, he saw Aurora walking down the street. He liked Aurora so much that he didn’t want to meet the other girl. They had one son named Ernesto who was born in Havana (known to Cubans as La Habana).

They lived in Havana because Boni worked at a dry cleaner and laundry service whose owner was Japanese. They lived there for about fifteen years from 1953-1968 which was when they both emigrated to the United States under the once Castro took power.2

Her younger sister Obdulia ended up living with her and Boni for eight years in a Havana district called La Víbora. It was very safe and they had good neighbors. Aurora felt that the Cubans respected the Japanese like they were high class. They did not own a car and utilized the gua-gua (bus) which cost two cents at the time.

Obdulia Yoshimura was born on July 14, 1928 in Jatibonico. She often listened to novelas (soap operas) on the radio—one show in particular named Mama Dolores. Dolores was a young black woman who adopted a child named Albertico Limonta. Obdulia had an overall great memory of her time living in Cuba. Life was good and simple.

The final sister Sumie (Luisa) Yoshimura, born on December 4, 1931, worked in a coffee shop in Jatibonico. When she came to the U.S. she went to beauty school, spent time making hearing aids, and also worked at Sumitomo Bank where she only spoke Spanish. All six sisters grew up in a fairly comfortable environment until their lives were affected by forces way beyond their control.

After Fidel Castro successfully overthrew the regime of General Fulgencio Batista, many changes took place. Many changes were aimed at improving conditions in the countryside, raising education standards, and leveling the playing field for all Cubans.

However, the Shimomura, Yoshimura, and Matsumoto families were all dissatisfied with the changes. The family ice cream shops were nationalized and shut down. The government appropriated lots of privately owned property and money. Long lines for everything from food to toys were becoming the norm, and life for them in Cuba became more about surviving than living. The conditions in Cuba ultimately led to the family decision to leave the homeland for America.

Life in the United States has been rewarding for my family. The Catholic church played a large role in acclimating my family to the United States and finding jobs in San Francisco, California.

Magaly Shimomura, Luis Shimomura, and Norma Ohashi all have children in the United States. Magaly “Maggie” Cheng has two children—me and my sister Allison. Luis has two children Michael and Melodie; and Norma Neeley has two children, Linda Grace Sutton (from her first marriage), and Christopher Michael Neeley. Linda died her freshman year in 1998 from an undiagnosed heart defect while attending the University of California, Santa Barbara. I was also in my freshman year at the University of California, Los Angeles, and suffice to say it was a difficult time for the entire family.

Her brother, Chris Neeley, is currently studying at the University of Santa Clara. My sister Allison, who was adopted from South Korea when she was three months old, is currently at Saddleback College in Mission Viejo, California pursuing a career in graphic design. Michael Shimomura graduated from the Academy of Arts University in San Francisco, and his sister Melodie from the University of California, San Diego.

With regards to Cuban members of my family, there is more to tell, as there always is with any family history. It was my hope and desire to initiate the documentation of one side of my family history for this project, and I look forward to documenting more of it in the future.

Watch “Chris Cheng visits his family's hometown, Sagua la Grande, Cuba 2006”

Notes:

1. Calle Colón #102, e/ Plácido y General Lee, Sagua la Grande, Villa Clara 52310

2. United States Government. Department of State. Treaties and Other International Acts Series 6063: Movement Between the United States of America and Cuba. Library of Congress, Washington, DC: 1966. The United States (through the Embassy of Switzerland) and Cuba agreed to the movement of Cuban refugees into the United States through an exchange of notes. They were signed in Havana on November 6, 1965 and also entered into force the same day. The United States agreed to take from 3,000-4,000 refugees per month. The terms did not specify any amount of refugees Cuba was to allow to leave. It is highly probably that as a result of this exchange of notes my family was able to leave Cuba.

* This article is an excerpt from the master’s research project, “Japanese Cubans: Past, Present, and Future,” by Christopher David Cheng (Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, December 19, 2006).

© 2006 Christopher David Cheng