A note on names: The names of the Issei photographers, including Shimotsusa even though he returned to Japan, are presented in Western order, that is, personal name followed by surname. For the names of Japanese nationals in Japan, I have maintained the Japanese custom of surnames preceding personal names.

Masashi Shimotsusa is one of forty photographers featured in the Japanese American National Museum’s current exhibition Making Waves: Japanese American Photography, 1920–1940, which runs until June 26, 2016.

Because he and at least two of the exhibition’s other photographers, J. T. Sata and Morinosuke Kamikihara, are known to have emigrated from Kagoshima Prefecture, it may be worthy to note that Shimazu Nariakira, the mid-19th century feudal lord (daimyo) of Kagoshima, formerly known as Satsuma, was the first Japanese to own a camera. Nariakira was regarded as the most brilliant and forward-thinking daimyo of the late Edo period. The camera was a daguerreotype set from Holland, which he imported through a Nagasaki merchant in 1848. A daguerreotype portrait of Nariakira is the oldest photograph taken by a Japanese known to exist.1

Whether or not Nariakira’s experimentation with photography had a direct impact on the three Issei photographers is questionable. It is undeniable though that his embrace of Western technology and art permeated the progressive factions in Kagoshima. Moreover, his adherents led the Boshin Civil War (1868–1869), resulting in the overthrow of the Tokugawa bakufu (shogunate) and the restoration of imperial rule. What followed were Japan’s rapid modernization and Westernization and the imperial decree to search the world for knowledge.2

Shimotsusa was born in the town of Kajiki in 1885; he was the second son of a distinguished samurai family. He matriculated at Kajiki Middle School and upon graduation his father directed him to apply for enrollment in the Japan Naval Academy at Etajima. The path expected of him was typical for a young man of his class. The Kagoshima region was well known for its martial spirit, and its former samurai (shizoku) dominated the top leadership posts of the Japanese navy during the Meiji period (1868–1912). Shimotsusa failed the Naval Academy’s physical examination because he did not meet the minimum weight requirement so he was advised to reapply during the next enrollment period. However, his father died that year, which freed him to pursue his own interests. He resolved to embark on an overseas adventure to study Western-style art. It was said that he was inspired by the example of his Kagoshima compatriots, Fujishima Takeji (1867–1943) and Kuroda Kiyoteru (1866–1924), who had studied art in Europe and promoted Western-style painting (yōga) in Japan.3

With money given to him by his older brother, Shimotsusa sailed from Kobe to San Francisco. He was nineteen years old.4 He traveled overland across the continent and sojourned in New York where he began his studies at a city art school. In New York he was introduced to photography and was privileged to come under the tutelage of a famous American photographer.5 Perhaps he attended the New York Institute of Photography as Morinosuke Kamikihara would do years later. In reminiscing about this time of his life, Shimotsusa stated that he derived so much more joy from photography than from other forms of art that he could not pull himself away from it.6 He found his true calling.

From New York he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to further his study of photography first in London and then in Paris. In France he apprenticed with the Lumiere Company, which had introduced commercial color photography in 1907. He was praised for the adept work that he did there.7

In 1918, Shimotsusa returned to America and opened a photography studio in Los Angeles. It was called Hakubundo, located at 250 East First Street in Little Tokyo. The following year he made a brief trip to Japan, just long enough to get married, and then returned to Los Angeles with his wife Toki (née Mayeda).8 They were not there long as it was later in 1919 that he decided to move to San Diego. Although Shimotsusa reportedly had a sizeable white clientele, he cited a surge in anti-Japanese sentiment as the reason for leaving Los Angeles.9 Competition may have been a contributing factor as well. According to Furukawa, there were twenty-seven Nikkei (ethnic Japanese) photographers in Los Angeles in 1918.10

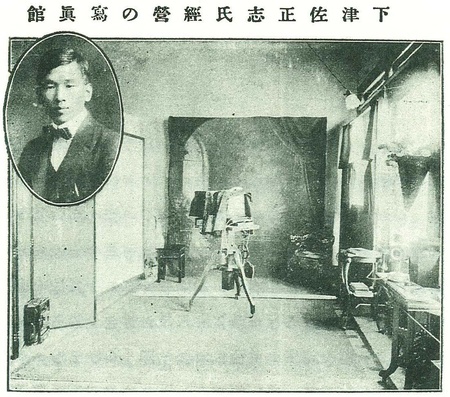

When the Shimotsusas arrived in San Diego in 1919, its Nihonmachi (Japantown) was concentrated around the intersection of Fifth and Island Avenues in the southern part of downtown. At the time, the Nikkei business district was comprised of six general merchandise stores, eight grocery stores, a doctor, two midwives, seven hotels, five Japanese restaurants, four Western-style cafes, four laundries, seven barbershops and baths, one fish market, and various other enterprises. Shimotsusa was the only ethnic Japanese photographer.11 His first photo studio, at 538 Fifth Avenue, was centrally located in Nihonmachi.12

It was while he was in San Diego that Shimotsusa enthusiastically set about becoming a pictorialist, that is, an artistic photographer.13 In a 1926 advertisement, he employed the phrases “artistic photography” and “camera artist.” His skill and creativity coupled with his penchant for trying the latest techniques and most up-to-date camera equipment resulted in photographs that were critically acclaimed.14 Ōkura described his works of this period as meisaku (masterpieces).15

In 1921, his photographs were accepted at the London International Photo Salon, and he exhibited widely in subsequent years. As stated in the American Annual of Photography, twenty-seven of his prints were seen in fourteen salons in 1926–27 and fifteen prints were exhibited in five salons in 1927–28. He submitted just one print to one salon during the following season.16 It was in 1927 that Shimotsusa was awarded the Grand Prix at the Budapest International Photo Contest in Hungary; he was forty-two years old.17

Because of the accolades and his rising prestige throughout the United States and abroad, he was invited to join the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, which was known to be an exclusive, white-only association. Shimotsusa was its first Asian member.18 Surely this was a source of great gratification for him.

Evidently, his interaction with the white community was important to him. The Issei in general were sensitive to how they were perceived by mainstream society, and perhaps Shimotsusa was even more sensitive being descended from Satsuma samurai.19 He probably equated acceptance by the white community with an elevation in status; it was undoubtedly good for business as well. When he had his studio in Los Angeles, he made it known that among his clients were many Hakujin meishi, “white celebrities.” Then in San Diego, around 1921, he moved his studio to 427 E. Street, several blocks north of the Nikkei business district. In an advertisement found in a Japanese-language newspaper, he described the new location as being in the heart of the white part of town (Hakujin machi chūshin). The advertisement was for a forthcoming photography school, which he was opening with, as he put it, the encouragement and backing of the white community (Hakujin no dōjō to kōen).

Shimotsusa’s vocational photography school opened on January 10, 1926, and both men and women were welcome to attend. Tuition was one hundred dollars for three months of instruction in taking photographs and training in retouching techniques that could be applied to “commercial as well as Kodak works.” In the aforementioned advertisement, he presented fourteen enticements to draw prospective students. Although his points may have been somewhat inflated in order to encourage enrollment, the following selection is nonetheless telling of the opportunities for ethnic Japanese in the photography industry as he saw them at the time:

- Commercial photography offers the potential to be profitable, and ethnic Japanese, if industrious, can compete with large white-owned photography companies.

- Retouching photographs as a part-time job, done at night or at home, can be a good way to supplement one’s income, especially for women.

- White photographers do not racially discriminate against ethnic Japanese technicians who are skilled and therefore high wages can be earned.

- Ethnic Japanese photographers have achieved respect in the United States, and those who have returned to Japan are quite successful there.

In touting his qualifications as the instructor, he stated that he had devoted twenty-five years of his life to photography with the previous eight years in business as the owner of his own studio. The final point listed above was a portent of momentous developments for the Shimotsusas.

In 1928, he and his family moved to Tokyo. He opened a studio in the upscale Roppongi district of Minato Ward, near the American Embassy. Shimotsusa distinguished himself as a commercial portrait photographer and was reputedly a favorite photographer among members of the nobility; government, military, and business leaders; preeminent academicians; and famous actresses.20

One of his most prominent subjects was Fleet Admiral Marquis Togo Heihachiro (1847–1934), a national hero who was world renowned as the naval victor of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). Shimotsusa and Admiral Togo took calligraphy lessons from the same sensei (instructor), Taniyama Shoshichiro, and it was Taniyama who introduced the photographer to the naval leader. All three hailed from Kagoshima. It was later discovered as a matter of coincidence that Shimotsusa’s father, an artillery gunner in the Satsuma army, and Togo served together during the Boshin Civil War. Shimotsusa took several pictures of Togo and was even given rare access to photograph the admiral lounging in his Tokyo residence dressed in Japanese leisure attire. The design of a four-sen postage stamp issued by the Japan Postal Service in 1937 was “patterned” on one of Shimotsusa’s formal portraits of Admiral Togo.21

Masashi Shimotsusa passed away in 1959 at the age of seventy-four. His son, Masanatsu, who had been born in San Diego in 1924 took over the photo studio and carried on his father’s vocation.22

Acknowledgments

I owe profound gratitude to Roy Asaki, a volunteer of the Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego, for translating into English the articles by Ōkura and Tsurukame. Any errors in the interpretation of the original sources are my own. I also wish to extend my heartfelt thanks to Linda Canada, archivist of the Japanese American Historical Society, for her generous support.

Notes:

1. Anne Tucker, Kotaro Iizawa, and Naoyuki Kinoshita, The History of Japanese Photography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 17. The portrait was taken by Nariakira’s retainers in September 1857. It has been designated by the Japanese government as an Important Cultural Property.

2. “To search the world for knowledge” comes from Article 5 of Emperor Meiji’s Charter Oath of 1868.

3. Kusayanagi Ōkura, “‘Torumono’ no jimbutsuzō” [‘The picture taker’ a personal portrait], Shūkan Asahi (November 29, 1974), page number unknown.

4. Akira Tsurukame, “Rekishi ni uzumoreta aru shashinke o motomete” [In pursuit of one photographer buried in history], Nanka Kagoshima Kenjinkai 110th Anniversary Commemorative Book 2009, 104.

5. Ōkura names him as ビッグロー, which may be the surname Bigelow.

6. Ōkura, page number unknown.

7. Tsurukame, 105.

8. Donald Estes, “A Moment in Time: Classic Photos from the JAHSSD Archives,” Footprints – Newsletter for the Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego 12, no. 1 (Spring 2003), 1.

9. Ōkura, page number unknown.

10. Eiji Furukawa, Nanka shū to Kagoshima kenjin [Southern California and the people from Kagoshima Prefecture] (Tokyo: Nihon Keisatsu Shimbunsha, 1920), 48.

11. Ibid., 84.

12. Estes, 1.

13. Furukawa, 190.

14. Ibid.

15 Ōkura, page number unknown.

16. Dennis Reed, Making Waves: Japanese American Photography, 1920–1940 (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2016), 150.

17. Ōkura, page number unknown.

18. Tsurukame, 105.

19. The late Robert K. Sakai, Professor Emeritus of the University of Hawaii, contended that the samurai in Kagoshima were the most haughty and status conscience of all Japan.

20. Ōkura, page number unknown.

21. Ibid.

22. Tsurukame, 105.

© 2016 Tim Asamen