Studying a language is a way to learn about the culture of a town or a country. And to know the ancient and modern culture of Japan, it is necessary to study its language and its forms of writing ( hiragana , katakana , kanji and rōmaji ), in addition to shodō (Japanese calligraphy) not out of duty, but for the enjoyment it produces. His learning. Those who teach it, those who have learned it and those who study it know it.

In Peru there are few places where you can learn Japanese. The best known is the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ), which has about 40 teachers (eight of them native Japanese) for the nearly 450 students who study every month at the three levels of education. Contrary to what one might believe, the highest percentage of students are young people interested in Japanese subculture, and who want to study or live in Japan.

“Kids come for manga, anime and pop music, but they end up becoming interested in history, literature and traditional Japanese culture,” says Antonio Takayama, pedagogical coordinator of the APJ Japanese Language Department, through which Various services are offered for those interested, of any age, in studying or putting into practice nihongo .

Seminars, conferences and refresher and improvement courses for Japanese teachers, at the national level, are a service they offer as part of their task of disseminating the language. This year, they will offer assistance to teachers from six provinces of Peru where, although there are no academies specialized in teaching, there are teachers in institutes or universities willing to make it known.

Passion before business

Although there is a sustained demand at the APJ and there are other study centers such as the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (both in their language centers) and the Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola (as part of their degree in International Business), the Japanese language is still not seen as a door to finding work in their country of origin.

Takayama points out that in Cusco some young people want to learn Japanese to work as tour guides and that the majority of students aim for a specialization or a professional career as an interpreter. “The scholarships are few enough to consider studying the language for this reason alone,” he clarifies that it can be an attractive market for guide work but the perspective of accessing existing scholarships should not be lost.

Far from scaring away young people who dream of traveling to Japan, the language makes them grow a passion that is palpable in the shodō or conversation clubs for young people, former scholarship holders and Japanese residents in Peru, who also encounter recreational spaces to share anecdotes and concerns about the practice of this language.

Living the language

Denise Goshima was born in Peru, she is an architect and second-generation Nikkei. Her grandparents spoke Japanese but her parents did not, so she had to learn the language in a couple of schools (in APJ and in Ichigokai) before traveling to Fukushima, in 2008, to do her specialization; returning a year later to earn his master's degree. She says that the most difficult thing is to let go and speak without worrying about mistakes.

“The important thing is that people understand you and that you lose your fear of speaking in Japanese,” says Denise, who confesses that when she arrived in Japan she did not feel prepared to use the language, but that colloquial conversations helped her become familiar. Furthermore, at the university where he studied, tutors were assigned to him and they explained some technical topics of the degree to him in English.

“Reading a newspaper is the most complicated thing,” says Denise, both because of the writing and the context. Plus, there were other situations I wasn't prepared for. “There are certain codes that you have to know,” he adds, saying that there is a colloquial language, a somewhat formal one that is used with older students (the senpai , those with more experience) and a very formal one to address the teachers. “That's why I recommend that those who travel to Japan speak first with someone who has been there.”

A long learning

The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges said in 1985: “somehow I will continue studying Japanese after my bodily death” to refer to how inexhaustible this language is. “In Japanese I think there are nine ways of counting things, and the words also vary according to the numbers […] there is a system that is used to count long and cylindrical things; this cane or a pencil or a pool cue. There is another one to count small or large animals.”

His lecture “My experience with Japan” illustrates what happens to many: although it has a less complicated grammar (verbs are not conjugated like in Spanish, for example), there are aspects that can only be understood when you know that some words They contain concepts and not just objects or people. As if that were not enough, the teaching of Japanese is different from that of English, since it involves memorizing situations.

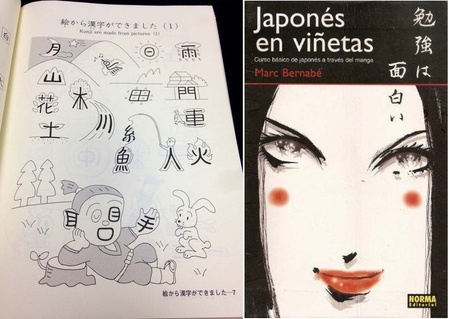

One of the ways in which children are taught to write is by relating the characters to the object they represent due to the similarity of the strokes. There are kanjis that are ideograms and others are pictograms. The most common way to know some words is by reading them in rōmaji (Roman characters according to Japanese pronunciation), where, for example, お弁当 means lunch box and should be read as ' obentou '.

A country full of culture

It is said that Japanese culture is very closed, which may have its origin or consequence in the fact that its language is spoken in only one country. To know it fully you need to know Japanese. Borges stated that in Japanese poetry there is almost no metaphor, “one thing is not compared to another. It's as if the Japanese feel that everything is unique." In Japanese, there are words that refer to unique and very specific ideas.

The Japanese expression ' Tsundoku ', for example, refers to book hoarders who buy books but do not read them; They just accumulate them. Denise Goshima remembers one that caught her attention: ' enrio ', the custom of not taking the last bite from a tray at a meeting out of courtesy, hoping that someone else will do it. And also one that he used and that he now misses in Spanish: daijoubu (which can be used to say that you don't need help, or to ask if someone who has fallen is okay).

Japanese is, in itself, a language full of culture, not to mention haikus , origami , ikebana , Japanese illustrations, ceremonies and religions. Currently, there are many ways to approach it through blogs such as Gambateando (by Peruvian Roberto Galarza), with videos that help you with pronunciation and in books such as Japanese in vignettes , by Spanish Marc Bernabé.

teach japanese

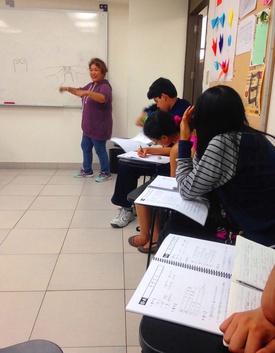

Ana Takahashi is a Japanese teacher at the Peruvian Japanese Association and believes that manga, anime and J-pop, as well as the internet, help students learn more about nihongo and learn it faster. “A Japanese student who is not interested in these topics will be at a disadvantage compared to his or her classmates,” he says, pointing out that to understand a language you have to understand its culture.

Traveling to Japan is another recommendation he makes for those who want to master the language. Being a tourist is not the same as living in the country, studying and working. With the latter, you get to know more about the idiosyncrasies of the Japanese, in aspects such as punctuality and the labor relationship. “You have to live the language,” he says. Therefore, in class he always makes the students talk. From the lowest level, all classes are in Japanese.

“Sometimes we go out in groups and practice real situations on the street,” says sensei Ana, who shares aspects of life in Japan with her students as part of her classes. He teaches them, for example, what a furuhon'ya is, a chain of second-hand book stores that abound in that country. “They have up to seven floors and you can find manga collections at a good price.” Living the language is spreading that enthusiasm for a country in which they never stop dreaming.

© 2016 Javier Garcia Wong-Kit