Camera Clubs

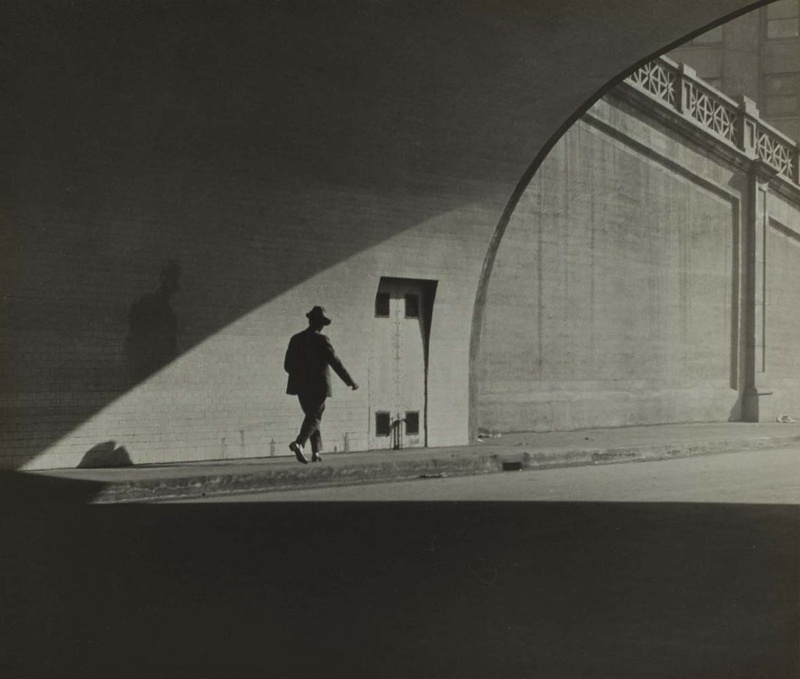

Besides spiritual philosophies and artistic approaches, there is human drama behind this exhibition. Dedicated Japanese American photographers operated in a difficult political and economic climate.

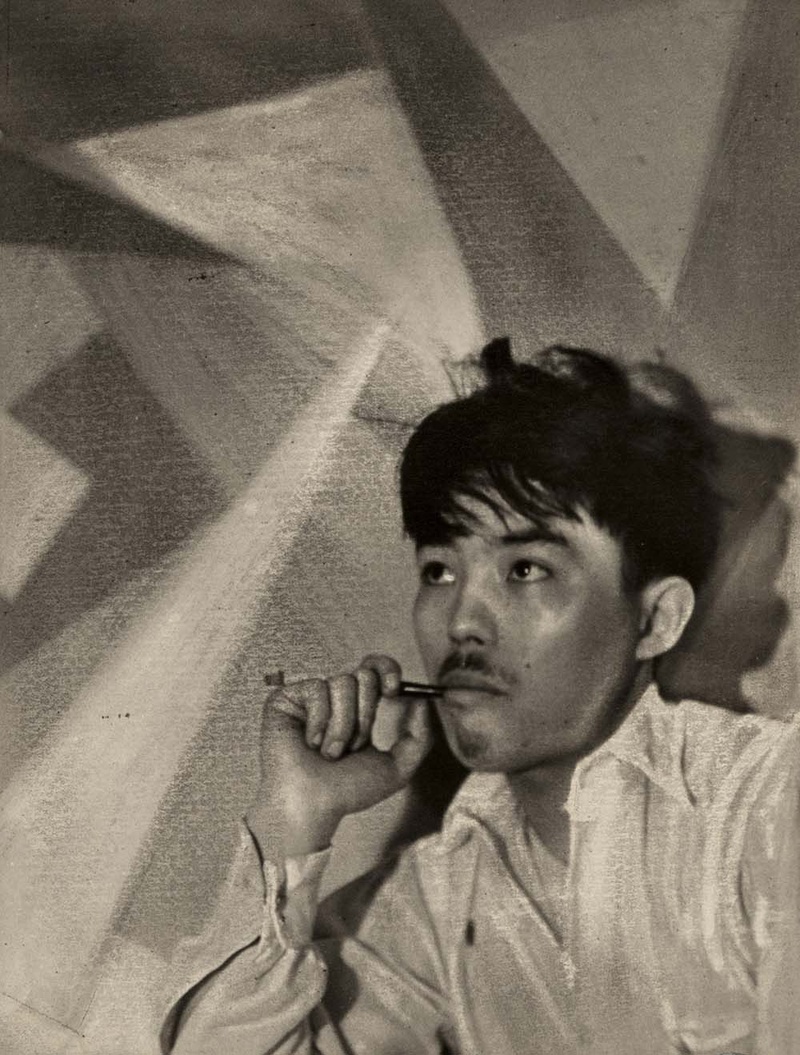

Roughly between 1920 and 1940, Nikkei photographers, who were primarily first-generation immigrants, or Issei, figured prominently in camera clubs and exhibitions on the West Coast of the United States, centered around Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle. There they found camaraderie, companions for photographic outings, and photographic advice.

In their day, the photographs by Japanese Americans were widely accepted in pictorialist salons and publications that were run by Caucasians. However, Caucasian museum directors, curators, and gallery owners submitted to societal prejudice and steered clear of Nikkei photographers. It was a time when laws that restricted immigration, citizenship, and property rights affected Japanese Americans.

Japanese Americans, like other immigrants and their families, certainly formed close friendships among themselves and founded mutual aid organizations. But Nikkei photographers also assimilated into the mainstream of society, and swapped ideas with Caucasians, locally and even internationally. Sometimes, however, Nikkei were ostracized. For instance, none were ever invited to belong to the strictly Caucasian club of Camera Pictorialists in Los Angeles. However, many Camera Pictorialists, such as Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, Will Connell, and Arthur Kales, frequented Nikkei camera club meetings and studios. And the Camera Pictorialist club did include some Japanese Americans’ photos in catalogs for annual international exhibitions.

On the West Coast, almost no Caucasians opted to belong to camera clubs where Nikkei already formed a huge majority. This was even true of the Seattle Camera Club, where a few Caucasian and female members (Japanese and White women) were definitely made to feel welcome. A well-known example is a woman named Ella McBride, who relocated to Seattle to assist Edward Curtis, the renowned photographer of the U.S. West and Native American tribes in the region. She soon managed Curtis’s studio, and, eventually, McBride opened up her own studio. She photographed portraits and landscapes, but became best known for her delicate floral studies with obvious Japanese design influences.

The predominantly Nikkei Seattle Camera Club was inclusive, artistically as well as ethnically. Among its guest lecturers were non-photographers and Caucasians, including Glenn Hughes, who fit into both categories. He was a University of Washington professor of English, who spoke about innovations in theatrical effects like stage lighting. The broad-minded members of the club even discussed photos by Japanese American Frank Kunishige that included partially clad or totally nude human figures that were ambiguous in race or gender.

Despite much critical acclaim, most of the Nikkei photographers were hobbyists. The few who earned money from photography did so only part-time, having little commercial success, surviving mostly by other means. A handful owned camera shops, purveying photographic equipment and supplies, making negatives and prints, maybe even selling their own and others’ photographs. Establishments like the T. Iwata Art Store in Los Angeles provided employment for some photographers and a gathering place for all to enjoy and critique each other’s pictures. The Korin chain of camera shops in Los Angeles, run by Taizo Kato and Kamejiro Sawa, additionally sold stationery, frames, and a variety of fine arts. Kato was a painter as well as a photographer.

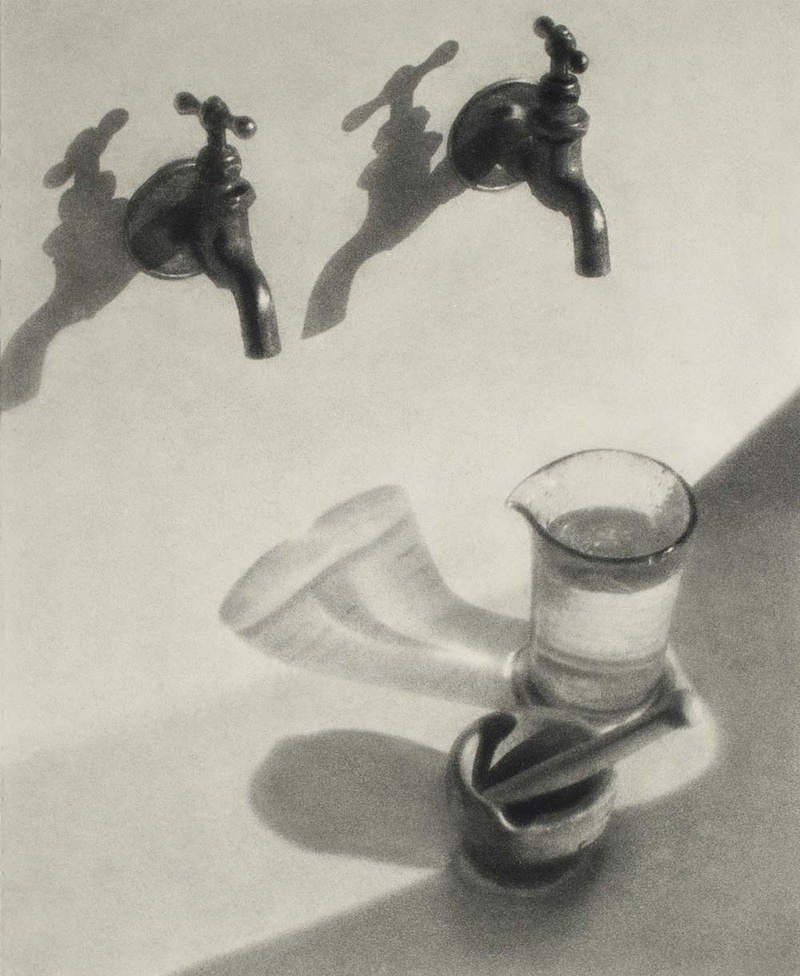

Most of the Nikkei photographers held jobs as cooks, dry goods salesmen, gardeners, and the like. For them, photography was an expensive hobby, with a camera typically costing nearly $100, approximately one month’s salary. And there was the expense of other equipment like tripods and filters, as well as supplies for developing negatives and making prints. Few Nikkei photographers had the money for more costly technology, like unconventional inks and printing processes that went beyond using simple chemical toners and mimicked fine art etchings.

The stock market crash of 1929 devastated Nikkei photographers like most everyone else. Many were now permanently stuck in low-paying, blue-collar jobs—that is, if they were still employed at all. A substantial percentage of them could no longer afford to be involved in photography as a hobby or source of modest income. Some Nikkei photographers returned in despair to Japan.

Even in the 1920s, a fortunate few Nikkei photographers had professional day jobs, often pursuing a variety of cultural interests. One prominent example is Kyo Koike, who was a physician. He founded and presided over the Seattle Camera Club. Dr. Koike contributed articles of his own to the monthly bilingual bulletin, and edited others’ submissions. He also wrote for national photography magazines, employing a lively style that often addressed the reader directly. Koike archived issues of the club’s bulletin, which survive to this day. His close friend, Iwao Matsushita, saved club records, photographs, and exhibition books, and eventually donated them to the University of Washington Library. When the Seattle Camera Club disbanded in 1929, Koike devoted more of his attention to other endeavors, such as writing about Japanese literature and cataloging his specimen collection of regional flora.

World War II Incarceration of Japanese Americans

During Kyo Koike’s incarceration during World War II as a Japanese alien, he held classes in haiku poetry and published work that was written by himself and fellow incarcerees. After the war, he reopened his medical practice in Seattle.

Before being relocated to incarceration camps, some Nikkei photographers destroyed their work. Others hid the photographs or gave them to relatives and non-Japanese American friends for safekeeping. Many photos were never recovered. The Nikkei fully realized that their camera clubs were widely considered by American authorities to be pro-Japanese societies. Bowed but not broken, many proud Nikkei appeared in their finest attire as they boarded buses bound for temporary assembly centers with awful living quarters like horse stalls at the Santa Anita race track near Los Angeles. In the meantime, permanent incarceration camps were being constructed in several states.

In the War Relocation Centers, any radios and cameras held by Nikkei were officially considered contraband and subject to confiscation. The federal government was on the lookout for espionage and sabotage by Nikkei, but during the war, not a single act of treason ever happened. Some individual camp administrators unofficially allowed Nikkei to own and operate cameras.

Toyo Miyatake was incarcerated at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in a remote location alongside the Sierra Nevada mountain range. At Manzanar, Miyatake smuggled in a camera lens. After building a camera body out of wood, he proceeded to photograph life there secretly, barbed wire fences and all. A Caucasian friend from Los Angeles sneaked film into the camp whenever he openly delivered equipment on authorized visits. When other sympathetic Caucasians, in their role as camp officials, uncovered Miyatake’s hidden makeshift camera, they allowed Miyatake to retrieve his factory-made camera that was in storage in Los Angeles and continue his work under supervision, indoors and eventually outdoors.

A decade earlier, in 1932, Miyatake, who then owned a photography studio in Little Tokyo, was exhibiting his own photos of Nikkei lining the streets of Little Tokyo, celebrating the Los Angeles Olympics, in front of buildings where they had planted U.S. and Japanese flags and festive decorations. Japanese American hope and resilience were on public display in the depths of the Great Depression. Now, at Manzanar, realistic images of highly individualized human faces, without decorative touches, were taking center stage.

Jack Iwata, who had worked in Miyatake’s Los Angeles studio before the war and then helped Miyatake set up the studio at Manzanar, received a transfer to Tule Lake Segregation Center. There he immediately got permission to document the lives of detainees through photography.

A few Caucasian photographers were commissioned to take photographs of the camps—with mixed results. Dorothea Lange, known for her moving photos during the Great Depression, provided revealing, powerful images of the confinement of Japanese Americans. But Ansel Adams was not allowed by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to photograph disturbing sights at Manzanar like guard towers and barbed wire, thereby sanitizing his images.

After the war, many Nikkei often could not afford to buy back property that they had sold at fire-sale prices after receiving relocation notices. Also, persisting discrimination, worsened by the war, now made it harder for Nikkei to find housing and jobs. Economics and the need to rebuild their lives prevented many Nikkei from re-establishing their connection to photography.

Recognition

This exhibition goes a long way toward enlightening the public about these Nikkei photographers’ struggles and accomplishments. The exhibition illuminates Japanese American culture and how its heirs in the diaspora faithfully clung to their traditions, open-mindedly absorbed outside cultural influences, and shared with the world an art form with strong design elements and spirituality. It is appealing and meaningful photography that can be universally understood and appreciated with a modicum of reflection and further study.

References

Bromberg, Nicolette. “Preserving a Legacy of Light and Shadow: Iwao Matsushita, Kyo Koike, and the Seattle Camera Club.” Shadows of a Fleeting World: Pictorial Photography and the Seattle Camera Club (2011).

Carroll, Jill. “Shinto Beliefs,” World-Religions-Professor.com.

Guth, Christine M. E. “Japanese Art and Architecture.” The New Book of Knowledge®.

Hosteler, Lisa. “Pictorialism in America.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art (October 2004).

Ives, Colta. “Japonisme.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art (October 2004).

Japanese American National Museum. “JANM to Open Two Photography Exhibitions.” Janm.org (January 20, 2016).

—. Making Waves: Japanese American Photography 1920-1940. (2016).

May, Matthew. “Zen and the Art of Simplicity.” Roman Magazine. (Fall 2011).

McArthur, Meher. “Japan’s Photographers Reflect the Realities of a Changing World.” KCET Artbound (April 18, 2013).

Martin, David F., “McBride, Ella E. (1862-1965)” HistoryLink.org (March 3, 2008).

Sailor, Rachel. “’You Must Become Dreamy’: Complicating Japanese-American Pictorialism and the Early Twentieth-Century Regional West.” European Journal of American Studies Vol 9, No.3 (2014).

Seattle Camera Club. “Dr. Kyo Koike, 1878-1947.”

Seattle Camera Club. “Frank Asakichi Kunishige, 1878-1960.”

United States Department of State. “Milestones: 1830-1860: The United States and the Opening to Japan, 1853.” Office of the Historian.

WAWAZA. “When Less is More: Concept of Japanese ‘MA.’”

Whitney Museum of American Art at Equitable Center. Japanese Photography in America, 1920-40 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1988).

* * * * *

Making Waves: Japanese American Photography, 1920–1940

Japanese American National Museum

February 28 – June 26, 2016

Making Waves: Japanese American Photography, 1920–1940 is an in-depth examination of the contributions of Japanese Americans to photography, particularly modernist photography, much of which was lost as a result of the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The exhibition, curated by photography historian and educator Dennis Reed, presents 103 surviving works from that period alongside artifacts and ephemera that help bring the era to life.

© 2016 Edward Richstone