Post Second World War

The reintegration of veterans to civilian life after the end of hostilities was a challenge for Canadian society in general and at universities in particular and the University of Manitoba was no exception. In 1947, university president Albert W. Trueman observed that returning veterans taxed the administrative capacity with student registration at the U of M reaching “the unprecedented figure of 6,919.” The presence of “such an army of students” imposed “severe strains on the institution,” declared Trueman with the university administration scrambling to find staff, space, and equipment for returning veterans that had their education interrupted as well as for a younger cohort that did not see military service. Indeed, the department of architecture and interior design also grew from sixty students in 1945 to over 400 by 1948, years that coincided with the presence of Kiyoshi Izumi and his close friend, classmate and future business partner, Winnipeg-native Gordon Arnott. The importance of the friendship between Kiyoshi and Gordon as young adults at the University of Manitoba within the context of a nation at war cannot be overstated. With many of their classmates and age cohorts engaged in conflict, many in the Pacific theatre, this friendship between a Japanese Canadian and a Euro-Canadian must have been unique. That said—and allowing for youthful exuberance—the student year book Brown and Gold referred to the graduating Kiyoshi as a “solid citizen who claims the world for his home.”1 It must be remarked that of the 17 students that graduated from the school of architecture in 1948, Izumi was the only student not listed with a hometown—an acknowledgement of his up-rootedness as a Japanese Canadian from British Columbia.

The city of Winnipeg, the capital of Manitoba and the largest city on the Canadian prairies in the mid-twentieth century also saw limitations placed on Japanese Canadians. By the time Izumi arrived in 1944 to attend the University of Manitoba, restriction of movement, residence, and employment was problematic. In spite of such constraints, Japanese Canadians were permitted to attend university and live in the city. There was dependence on individual Euro-Canadian acts of generosity. Initially, friend of Kiyoshi and engineering student James Sugiyama had difficulty finding accommodations until he attained “room and board with the help of a recommendation from a professor.” Sugiyama quickly: proved himself to be an intelligent and conscientious youth, so the family [that provided room and board] welcomed eight more Japanese [Canadian] students into their home. The father of the house was a painter and during the summer vacation he gave students painting jobs which greatly eased their financial situations.2 Izumi returned to Regina during his summer holidays to work at the Japanese Canadian owned Imperial Service Station and Tire Repair Shop (managed by future father-in-law, Charles Nomura) and because of his future wife Amy Nomura.

After graduating from the University of Manitoba School of Architecture in 1948, Kiyoshi became a graduate student of urban planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) at Harvard from 1950–1954. If there was a profession that Nisei could do relatively well in spite of racism during and in the decades after the Second World War, it was architecture. According to one American Nisei architect:

…architecture’s been very, very reasonable, nice to [N]iseis,… Because I’m Japanese [American], I think [customers came] to me sometimes, you know. It’s not because [Japanese Americans had a monopoly on] creativeness, but, there’s some association there. And I [did not] try to discourage that thought, [and] those [Nisei] that went into architecture did very well… Yama [Minoru Yamasaki, designer of the original Twin Towers was] a good one, Gyo Obata another one, Ryo Tamoto,…3

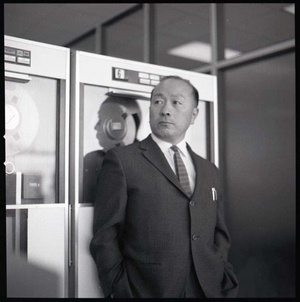

The Architect

There were structural and societal obstacles in attaining employment for Kiyoshi Izumi. Certainly, the architecture profession’s legacy “is one of patronage, privilege, and power” with success predicated on a “network of social connections.” Practitioners, were (and still are) dependent on wealthy and powerful patrons for their livelihoods. In a sparsely populated province such as Saskatchewan the number of wealthy clients were few and far between; thus the dependence on government largesse was amplified. Even so, the number of professional architects in Saskatchewan had dwindled to 16 by the beginning of the 1950s because of the Great Depression and the Second World War, making it opportune for the highly credentialed Izumi to return to a post-war province in 1953 that did not have as racist a reputation regarding Japanese Canadians. The partnership in 1953 between Kiyoshi (the elder by five years) and his classmate Gordon Arnott—six years after graduating from the University of Manitoba—also reveals much at a personal and a professional level. It was Kiyoshi, who was living again in Regina after his graduate studies, who asked Gordon, then working in Vancouver in the early 1950s, to form a partnership.4

In 1954, Izumi was asked by the Saskatchewan government to evaluate the province’s mental hospitals, more specifically, to make suggestions on how to modify and redesign hospital environments for the benefit of patients from the perspective of patients. Initially, the self-critical architect had difficulty grasping “the real and significant problems” a mentally ill individual had in relating to their physical environment. As such, with advice and direction from Humphry Osmond, Kiyoshi took LSD, which produced an experience similar to schizophrenia. The practical architect also wanted to identify with mental patients’ needs for privacy and yet design the best possible housing at the least expense, the latter satisfying the fiscal considerations of his employer (the government of Saskatchewan).The result of this partnership saw the construction of the Yorkton Centre in 1964 though the government of the day did not fully implement the design by Izumi. The empathetic Izumi noted in his initial experiments with LSD that his “visually perceived world” became a “part of the space-time framework of reference, in and from which one relates to himself and to others, but at times is an extension and an indistinguishable part of one’s mind and body.” At the same time, Kiyoshi’s taking of the hallucinogen were a means of communication that enhanced the “emotional experiences of [mental patients]…, and whose needs [were] just as important.”5

At the same time, Izumi’s reputation as a leading Saskatchewan architect was enhanced as the Regina-resident was one of the key organizers for the “Saskatchewan Symposium on Architecture” in October 1961. The symposium—which attracted 120 delegates from throughout the province and speakers with an international reputation—may also be considered the beginning of an architectural renaissance for the prairie province. At a panel discussion Kiyoshi stated that architecture in Saskatchewan suffered “from a lack of skilled personnel and facilities in many areas of the construction industry.” Indeed, there was an “apparent low value placed on architecture by the public,” generally. This architectural climate in Saskatchewan was about to change, in part, through the person of keynote speaker, Minoru Yamasaki. The internationally renowned Japanese American architect announced at the symposium that he had brought with him to the Queen City “a number of possible plans” towards the completion of a master plan for the Wascana Centre and the expansion of the University of Saskatchewan’s Regina campus, with provisions for a “grand entrance” to the university campus.6 The plans were expected to be approved by the Wascana Centre committee in 1962. Thus, the building boom of the 1960s was set to begin with the firm of Izumi, Arnott, and Sugiyama being a major contributor and beneficiary. The firm was responsible for designing some of the most recognizable buildings in Saskatchewan including Marquis Hall (1964) at the University of Saskatchewan, the Connexus Arts Centre (1970) formerly the Regina Centre of the Arts), and the downtown central location of the Regina Public Library (1962).

Epilogue

In 1968, at the age of 47 and after fifteen years of practice in architecture, Kiyoshi Izumi accepted a faculty position at the newly created Department of Environmental Studies at the University of Saskatchewan’s Regina campus. Later, from 1972 to 1986, Izumi taught at the University of Waterloo where he ended his career. Kiyoshi died in 1996 in Kitchener, Ontario, at the age of 75. Kiyoshi and Amy Nomura Izumi, along with others such as James Shunichi Sugiyama were among a handful of Nisei in the early–1940s that made Saskatchewan their home. Though less prominent than Tommy Shoyama and George Tamaki (as well as the Moose Jaw-born artist, Roy Kiyooka, who lived in Regina during the 1950s) Kiyoshi Izumi belonged to the generation of Nisei that struggled mightily and did not reach their full professional potential until the 1960s. To be sure, many never did reach their potential due to the racism from that era. In the final analysis, however, some light has finally been shed on Kiyoshi Izumi and some of his Nisei associates that made Saskatchewan their home from the turbulent 1940s to the 1960s.

Notes:

1. University of Manitoba Archives (Hereinafter referred to as UMA). The Brown and Gold, 1947, 6; The Brown and Gold, 1948, 104.

2. Nakayama, 138.

3. Interview with George Matsumoto, “From Confinement to College: Video Oral Histories of Japanese American Students in World War II.” (accessed October 12, 2013).

4. Kaplan, Victoria. Structural Inequality: Black Architects in the United States. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006), 19; Flaman, Bernard Architecture of Saskatchewan: A Visual Journey (Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina, 2013), 32; Arnott, Ryan. “Buried Treasure,” in Regina’s Secret Spaces: Love and Lore of Local Geography, edited by Lorne Beug, Anne Campbell, Jeannie Mah (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 2006), 118-119.

5. Hoffer, Abram. Adventures in Psychiatry: the scientific memoirs of Dr. Abram Hoffer (Caledon, Ont.: KOS Publishing Inc., 2005), 154-155; Kiyoshi Izumi, “Some Considerations on the Art of Architecture and Art in Architecture,” The Structurist, No 2, (1961-1962), 47-48. For scholarship on Saskatchewan’s contribution to LSD research in ameliorating schizophrenia and alcoholism see Erika Dyck’s Psychedelic Psychiatry: LSD From Clinic to Campus (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 146.

6. Grain elevators “symbolic of Sask.” Regina Leader-Post, Saturday, October 21, 1961. Pg. 32; “Location of university buildings taking shape—Yamasaki discusses Wascana Centre,” Regina Leader-Post, October 20, 1961, pg. 3.

*This article was originally published in the Nikkei Images (Spring 2015, Volume 20, No. 1), a publication of the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre.

© 2015 Kam Teo