On July 8, 1867, the Chicago Tribune reported a love story between a Chicago girl and a Japanese acrobat. Traveling acrobats were most likely the first Japanese people who came to Chicago after the Shogunate began allowing ordinary people to go overseas in 1866. “Out of the very first seventy-one ‘passports’ granted to ordinary citizens by the feudal government, most were issued to the members of acrobatic troupes.”1 In 1869, the transcontinental railroad was completed, and many delegates and students sent by the new Meiji government rushed to the US, especially the eastern part of the country, and Europe, in order to study western technologies and arts. They passed through Chicago to change trains, but very few stayed to live in Chicago.

It was in 1880 that the Illinois census officially recorded the first three Japanese living in the state. One was J. Yanada in Galena, a butler to former President Ulysses Grant, and the other two—a woman and a man—lived in Chicago. Little is known about the Japanese woman at this point, but the man was Michitaro Ongawa, who later became a popular performer of Japanese dance and songs on the Chautauqua circuit from the 1910s to the 1930s. J. Yanada went back to Japan in the spring of 18842, but Ongawa stayed in the Chicago area for the rest of his life.

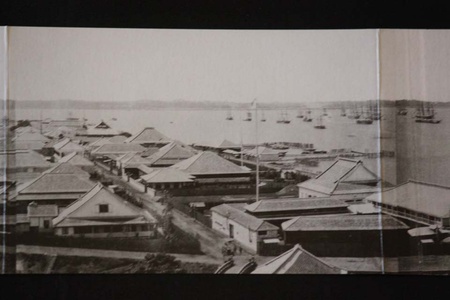

Ongawa’s original name was Michitaro Ogawa. He was born in Tokyo on February 21, 18593, and lived in Yokohama, where a foreign concession was established the year he was born. In that concession, there were many missionaries from various churches who hoped to spread Christianity by teaching English using the Bible as a textbook. One of them was Christopher Carrothers, a Presbyterian missionary. Born in Ohio, Carrothers graduated from the University of Chicago in 18674 and completed the Illinois Presbyterian Theological Seminary in 1869. He arrived in Yokohama in late June 1869 with his wife Julia.5

Carrothers’ mentor, Edward Cornes, was also a Presbyterian missionary. Cornes knew Carrothers in college in Pennsylvania, as well as at the Illinois Presbyterian Theological Seminary, and it was he who encouraged Carrothers to work in Japan. Cornes had gone to Japan in 1868, one year earlier than Carrothers.

Christopher and Julia Carrothers started a private school in their home. Their first students were young boys. They offered two kinds of classes: a samurai class and a regular class.6 “Michitaro” must have been a familiar name to Julia, as she mentioned it as an example of a Japanese boy’s name in a book about her life in Japan, published in 1879.7 Julia also called Michitaro’s uncle, Yoshiyasu Ogawa, “Ongawa.”8 “Ongawa” seems to be how the name “Ogawa” sounded to English speakers.

On August 1, 1870, a tragedy occurred in the Presbyterian missionary community. The boiler on the steamship City of Yeddo, bound for Yokohama, exploded just before departure. Edward Cornes, his wife Elisa, their firstborn son Eddie, and their young English nurse were killed in the incident. Only their three-month-old baby, Harry, survived.

Julia decided to take Harry to the home of a Cornes family friend in Iowa in February 1871.9 What is most interesting is that she took not only Harry but also Michitaro with her to the US. It is notable that Michitaro’s passport had already been issued in 1869, not after the tragedy of 1870, and that the purpose for travel indicated on the passport application was to come to the US to be a servant of Carrothers.10 This means that Michitaro’s trip to the US had probably been planned before Carrothers’ arrival in Japan. In fact, Cornes had written to the church in 1869 that “one boy [is] learning very fast in [his] English Class. Hope to train him for service to his countrymen. Abundant reason to be encouraged. Very little to discourage.”11

In those days, Christianity was prohibited in Japan, so missionary work was closely monitored by the government. Although Cornes did not mention Michitaro by name, the boy mentioned in the letter is most likely Michitaro because Christopher Carrothers also wrote to the church as follows:

The Japanese boy she took with her is a very smart and promising youth. … The fact that none of his relatives will be likely to lead him away from our influence after he is educated is encouraging. His father and mother are both dead, and his uncle who had charge of him is Mr. Thompson’s teacher and a baptized Christian.12

David Thompson, another Presbyterian missionary, had been in Japan since 1863. Michitaro’s uncle, Yoshiyasu Ogawa, who had been Thompson and Cornes’ Japanese language teacher, was well known in the Yokohama missionary community. Yoshiyasu was baptized by Thompson in 1869, and became the first Japanese pastor in the Japanese Christian church in 1877. Both Yoshiyasu and Michitaro were deeply involved with Presbyterian missionary work in Yokohama; Michitaro was only about 11 years old when his passport was issued in 1869.

Because her father, Richard Varick Dodge, was the minister of a Presbyterian church in Madison, Wisconsin, Julia brought Michitaro to Madison. The April 2, 1871, issue of the Wisconsin State Journal reported on Michitaro’s arrival as follows: “Ungawa, [is] between 12 and 13 years of age, but small for his years. He is gentle looking, refined in his appearance, and very polite in his manners. The lad seems a bright boy and, dressed like American children, he would hardly attract the notice of a casual observer.”

Before Julia went back to Japan in early 1872, she again visited Madison in late fall 1871. She wrote to the church: “The little Japanese boy who I brought with me is now with us. Studying quite hard. He is a bright boy and seems anxious to please.”13 It can be assumed that Michitaro was with the Reverend Dodge and his family in Madison until Reverend Dodge left for San Francisco in 1872. But did Michitaro leave Madison with them?

Notes:

1. Frederik L. Schodt, Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe (Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2012), 142.

2. John Simon, ed, The Papers of Ulysses Grant Volume 31 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), 98.

3. Illinois Deaths and Stillbirth Index 1916–1947 (Ancestry.com).

4. 8th Annual Catalogue of the University of Chicago 1866–1867. The Old University of Chicago Records 1856–1890, Box 5 Folder 6.

5. Memoir, William Elliot Griffis Collection from Rutgers University Library, Japan Through Western Eyes, Part 3, Reel 28.

6. Julia Carrothers, The Sunrise Kingdom: Or, Life and Scenes in Japan and Woman’s Work for Woman There (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1879), 56–57, 93.

7. Ibid, 89.

8. Ibid, 153, 196, 370.

9. Hepburn’s letter to Griffis dated November 18, 1895. William Elliot Griffis Collection, Japan Through Western Eyes, Part 3, Reel 31.

10. Passport issuing record, Foreign Ministry of Japan, Tokyo, Japan, Microfilm 3-8-5-2, Kanagawa Prefecture, Vol. 1, Reel No. Passport 3.

11. Cornes’ letter to Lowrie, dated January 30, 1869, summary. Japan Letters 1869–1873, Volume 2, Records of US Presbyterian Missions, Yokohama Open Port Library, Japan.

12. Christopher Carrothers’ letter to Lowrie, dated March 18, 1871. Japan Letters 1869–1873, Volume 2, Records of US Presbyterian Missions, Yokohama Open Port Library, Japan.

13. Julia Carrothers’ letter to Lowrie, dated November 16, 1871. Japan Letters 1869–1873, Volume 2, Records of US Presbyterian Missions, Yokohama Open Port Library, Japan.

* This article was based on a paper presented at the 18th annual conference on Illinois History on October 7, 2016, in Springfield, IL.

© 2016 Takako Day