Japan is full of so many art forms that there are some little known outside their country, even in Peru, where the Nikkei community has developed and spread many of them, such as ikebana , bonsai , origami and manga. This is the only way to explain why there is only one exponent of kamishibai , the paper theater that emerged after the Second World War as a kind of street art.

This is explained by Pepe Cabana Kojachi, known as “Mukashi Mukashi” (which means “a long, long time ago”), who began his path as a storyteller after leaving his job as a graphic designer, and who for almost 10 years has been the only one who spreads kamishibai in the country, mixing his two roots, the Ayacuchana from Peru and the Japanese, which comes from his migrant grandfather.

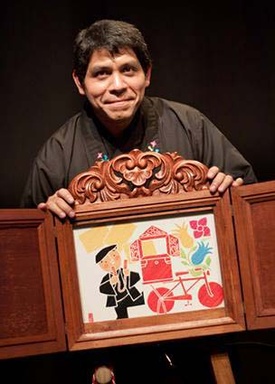

“I realized that in kamishibai I could capture my two roots, fusing the Ayacucho altarpiece and Japanese paper theater.” And in this Japanese art, a wooden theater called butai is used, in which the sheets with images that help tell a story are kept. This is what candy sellers did in Japan after World War II, and it was continued by kamishibai artisans.

Traveling Kamishibai

“Many believe that it has ancient origins, but kamishibai arose with these vendors who rode bicycles,” explains Pepe, who also uses the same transportation to carry his paper art and with which he has been able to reach Argentina, Chile, Colombia. , Cuba, Mexico, Spain, Paraguay, the United States and Poland, starting by recreating classic Japanese stories.

His first Japanese stories were How Fast a Witch Can Eat , The Friendship of Ogres , and Dragon's Tears . Cabana Kojachi says that it was in Argentina where he first saw this art for children that he had already heard about but that had no exponents in Peru. When he began his own path, he wanted to transmit Japanese art. Then it grew.

He has made Shakespeare stories, Greek tales and commissioned narrations, which has made him the pioneer of kamishibai, to which he now dedicates himself full time, performing in almost all the theatrical and cultural circuits of Peru. However, it has been in Chile where he has been able to give workshops to train other storytellers and it has been in Poland where he has been received as a Nikkei celebrity.

A story that grows

“In Chile I was surprised that the kamishibai was adopted by the government; all public libraries have this resource for storytelling,” explains Pepe, who has set an ambitious goal: to bring the kamishibai to public and private schools throughout the country. , where he hopes that this form of theater with visual support will help capture the attention of children and motivate them to make their own stories.

During the Ricardo Palma Book Fair, in the Lima district of Miraflores, Mukashi Mukashi showed this art in which he combines acting, interaction and fun. Using a simple hat he transformed into a character who manages to dazzle with the rhythm of his voice, his accelerated phrasing and his command of the scene. The interaction is done with Japanese words and jubilant exclamations that the audience must pronounce at Pepe's signal.

“Kamishibai never fails, it is magical, it manages to capture children's attention, making them cross that line that separates fantasy from reality.” The awakening of emotions begins with the traditional hyoshigi, two wooden tablets that are hit together to call the public. “It is said that at one time there were more than five thousand storytellers in Japan,” says Pepe about the country that recently invited him to bring the kamishibai back home.

Kamishibai Nikkei in Japan

In November, one of Pepe Cabana's biggest dreams came true. Thanks to the support of AELUCOOP, he traveled to Japan to show his work and share experiences about Japanese paper theater. The kamishibai route passed through Tokyo, Kyoto, Hyogo and Okinawa, with a project that integrates professional training for identity, culture and the promotion of reading.

“It took 14 years of very patient waiting to make this dream come true, and I have made the most of it, leaving aside hours of sleep to stay awake and learn everything I could,” says Pepe, who was able to visit museums, bookstores, libraries and have experiences of the daily life of the Japanese, including their means of transportation such as the densha and shinkansen .

“In each of them I always found someone with a book in their hand, the taste for reading is impressive in Japan,” he explains. The trip is the beginning of a documentary project titled Raymi Kamishibai , which will seek to collect different experiences around this art for which the Peruvian has composed a song in Japanese that he premiered at a seminar organized by the International Kamishibai Association of Japan IKAJA.

During his stay in Okinawa, Pepe Cabana Kojachi visited the library of the Nishihara prefecture, his maternal grandfather's place of ancestry, where he left his four story publications. “It was a way of feeling that my grandfather was returning through my publications to the land of his roots.” The fantasy of dedicating himself entirely to kamishibai continues.

Stories and retellings

This year, Pepe also published Friends of the Stories , an independent edition in comic format about how to tell and share your stories; and Kami, kami, kamishibai (APJ, 2016), the first story that talks about the origin of Japanese paper theater, illustrated by himself. “Wars should not exist. Apparently, there is a winner, but in reality we all lose.”

Thus begins this work that inaugurates the children's collection, Nikkei series, of the Editorial Fund of the Peruvian Japanese Association. The author says that he wanted to include the theme of war in the story of kamishibai to show how after a tragedy there is always hope. Converted into a pedagogical resource, kamishibai is studied in universities, applied in schools and libraries.

In times of fascination with technology, this artisanal medium seems to have no limits. Pepe, neither. In recent months, he has been at musical shows, book fairs, master classes and teacher trainings, among other initiatives that have kamishibai center stage. However, Pepe continues to look for his successors, people and institutions that are infected with the magic of storytelling to expand this art.

With AELUCOOP Cooperativa de Ahorro y Crédito, it has been carrying out actions to promote Nikkei culture, education, identity and values, such as its trip to Japan. But his initiatives do not end: he says he has a collection of pieces with which a museum could be built and many ideas for Raymi Kamishibai . Paper art doesn't stop, neither does Pepe.

© 2016 Javier Garcia Wong-Kit