There are people for whom the parts do not add up, but rather get in the way, collide, and life is like a rigid framework in which for something to enter, something else must leave. The new does not add, but rather takes away, colliding with what exists. Other people, however, manage to harmonize their parts and integrate the new. Rosa Sakuda, a Peruvian granddaughter of Japanese who resides in Japan, belongs to this group.

She feels Peruvian, Japanese, Nikkei, all together. Like a fusion dish in which various ingredients and techniques converge, Rosa embraces all its identities. Living in Japan has expanded your ethnic and cultural wealth.

He was dekasegi in his first stage in the land of his ancestors. He arrived in 1990 at the age of 19 and stayed for a year and a half. He returned to Peru for a time and in 1997 he traveled to Japan again to study Japanese and work in a travel agency in Tokyo. During her second stage in Nihon she put down roots, started a family and became a mother.

Life, at first, as for all newcomers, was difficult. “Life in Japan is always shocking since we are far from family, another language, customs, ways of thinking, among countless situations.”

Japan was not the supermodern country that I had imagined, at least not for those who lived far from big cities, in houses “with a hole for a bathroom.”

Rosa remembers that at that time she had to walk many kilometers because she did not have a car or she would go months without trying Peruvian food because there were no supplies to prepare “a delicious Peruvian dish.” Thus, he had no choice but to eat Japanese food, which was often not to his liking.

In the early 1990s there was no Internet, so to communicate with his family in Peru he had to spend a thousand yen on a card to talk on the phone for just twenty minutes. It was difficult to stay informed about what was happening in the country. A bomb could explode and you would find out much later. And being a foreigner in Japan, a gaijin , meant working in a factory.

A lot has changed since then. "Currently we have comforts, we can eat our Peruvian food and we have access to all communication and information about Peru through the internet."

And being a foreigner no longer necessarily means that the only possible job destination is a factory. “Years ago, perhaps being considered a foreigner (although we were Peruvian Nikkei Japanese) meant not having opportunities to improve because you had to be purely Japanese,” he says.

Today is different. "With globalization and information through the Internet, in recent years, a foreigner or Nikkei can have the opportunity to get ahead since they know at least two languages and the customs of other countries."

There comes a key point: the language. Without it it is very difficult to open doors and integrate into Japanese society.

“Thanks to mastering Japanese and other languages such as English and Portuguese, apart from my mother tongue, many doors have opened for me, such as having a travel agency, teaching languages, collaborating with Mercado Latino magazine and being a volunteer. at the Sagamihara International Exchange Hall.”

Rosa reiterates: “Japan gives you the security to live in peace, but mastering Japanese is very important to integrate into society.”

ADDING CHINA AND HAWAII

“I have never had a problem with being considered a Peruvian Nikkei or gaijin. Over time it has given us many advantages,” says Rosa.

For her, identities are not exclusive or incompatible. Everything contributes, integrates and forms a unique combination.

“I always feel like a Peruvian Nikkei because I grew up in Peru despite also being Japanese. But because of the time spent in Japan and learning its culture and language, you feel like a Peruvian Nikkei Japanese living in Japan... All combined into one.”

Rosa says that her adaptation to Japanese society has not been difficult, as she has always found support. “The people who have surrounded me have always given me all their support to live, get ahead and learn the customs of Japan.”

“The Japanese people invite you to collaborate and participate in the community and in schools. That's why, as I always say, the language and having studies helps you integrate into society. Those who do not know the language may reject any participation within the Japanese community and their integration will be difficult,” he adds.

Rosa is married to Alfredo Koc, a visual artist who has a workshop in Kanagawa. They are parents of two children: Daiki (13), who draws, and Ritsuki (11), who creates works with polymer ceramics.

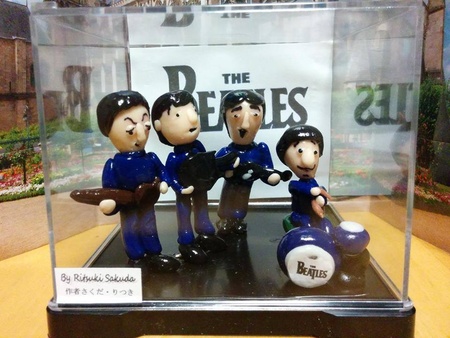

Ritsuki began making his first plasticine works at the age of nine and then jumped into polymer ceramics, with which he recreated famous people, from the Beatles to Doraemon.

Alfredo is of Chinese ancestry, so Ritsuki, born in Japan, has Peruvian, Chinese, and Japanese ancestors. Rosa says that her son “considers himself a Japanese Nikkei Peruvian Tusan.” In addition, he identifies with Hawaii, since his great-grandmother (Rosa's grandmother) was born in Oahu and they have family there whom they visit regularly.

Through art, Ritsuki nurtures his roots. His sculptures are related to Peru, Japan (Okinawa) and China. In December he will exhibit his works at the Peruvian consulate in Tokyo.

As a mother, Rosa is proud of her son, “because with his hands he can make beautiful and very detailed sculptures. People of any nationality can appreciate his talent and recognize it, which makes me very happy.”

Taking note of the variety or diversity that characterizes the Koc Sakuda family, it is inevitable to ask what customs are practiced in a multicultural home like theirs? What language do they speak?

“We generally live according to Peruvian customs, sometimes a little Japanese ones. The language used at home is Spanish, but my children use Japanese a lot for school and friends,” Rosa answers.

His case shows that it is not imperative to choose one ethnicity or culture at the expense of another. You can choose everything. And live well.

© 2016 Enrique Higa Sakuda