During my college days I once wrote an essay on the three ideals that I thought best epitomized the samurai: giri (duty), on (obligation), and chū (loyalty). It is no coincidence that a few years later as the coordinator of a Japanese American exhibition in the Imperial Valley Pioneers Museum, I had a hanging scroll custom made with the ideals that I thought best epitomized the Nikkei experience: giri, on, and gaman (perseverance). I very easily could have added loyalty to the scroll and gaman to my essay, but groupings of four are considered unlucky!

When I spoke to my professor of Japanese culture and society about my essay, I mentioned my samurai lineage. He replied that he had only heard Japanese Americans say such a thing and that he had lived in Japan and not once did he ever hear a Japanese national make the same claim.

I believe there is an explanation for how samurai became indelibly etched in the mindset of many Japanese Americans. It began in the early days of Japanese immigration and the attachment to our samurai cultural heritage continues among Nikkei to this day.

Samurai were among the earliest Japanese settlers in America. There were samurai with the colonists from Wakamatsu who arrived in El Dorado County, California, in 1869 with the ill-fated plan of growing tea and raising silk worms. As adherents of the Tokugawa shogunate, the Wakamatsu samurai were on the losing side of the Boshin Civil War, which led to the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and they opted to flee Japan.

On the opposite side, Kanaye Nagasawa was from Satsuma (present-day Kagoshima Prefecture). His lord opposed the Tokugawa regime, and in defiance of the shogunate’s isolationist policies Nagasawa was part of a group of young Satsuma samurai who were smuggled out of the country to study Western ways in Europe.

After the Meiji Restoration they were recalled to Japan by the new government to put into practice what they had learned abroad (one of them became Japan’s first minister of education). But Nagasawa did not go back to Japan. Instead, from Europe he sailed to America and eventually became the owner of a vineyard and world-renowned winery in Santa Rosa, California. The samurai was dubbed “the Grape King.”

I wrote in a previous article that there had been samurai in California’s Imperial Valley. Technically they were shizoku, a term applied to former samurai and their descendants after the Meiji Restoration. The shizoku classification was entered in family registers (koseki) until 1914.

Among the Imperial Valley’s shizoku was Sakusaburo Tokuda, a field supervisor for a produce company in Brawley. He and his forebears were listed as high-ranking retainers in the bukan of the lord of Numazu in present-day Shizuoka Prefecture. Bukan, typically translated as “book of heraldry,” were samurai registers of the Edo period (1600-1868). They are now sought out as resources by genealogists.

I once visited the Los Angeles home of Mary (Kawashima) Ota who in 1962 became the first Asian American woman principal of a California public school. On display in her living room were two magnificent ancestral swords that belonged to her father, Suezo Kawashima, who operated a grocery store in the Imperial Valley.

Shiro Koike, the sensei (instructor) of the Southern Imperial Valley Kendo Club, farmed in partnership with Tamizo Nimura in Holtville. Nimura’s son Takanori, better known as “Pro,” earned his shodan (first degree) under Koike Sensei’s tutelage. Pro once quipped that his father had to look after Koike Sensei’s farming activities because “he was no farmer; he was a samurai!”

And in Calexico an unassuming Issei sharecropper was rumored to have been a disciple of Yoshida Shōin, a samurai philosopher and supporter of the Sonnō jōi (Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians) movement. Shōin’s students played a key role in overthrowing the Tokugawa shogunate.

Over half of the Issei who arrived in America came from an agricultural background. As for the rest, I suspect that there was a significant number of shizoku although I have no way of knowing how many. The modernization and Westernization of Japan following the Meiji Restoration, which forced hundreds of thousands of farmers off their land, also displaced samurai who lost their special status and privileges during the same period. I also have a theory that the percentage of shizoku among Japanese immigrants was higher than the percentage of members of the upper class among Europeans who immigrated to America during the twentieth century.

To introduce the West to the virtues of Japan’s culture, Inazo Nitobe chose the moral principles of the samurai as the topic of his book Bushido: Soul of Japan. Nitobe, a samurai himself and perhaps Japan’s first true internationalist (he graduated from Johns Hopkins University, married a white American Quaker, and served as undersecretary of the League of Nations), wrote the book in English. It was first published in 1901 and although the material is somewhat dated now it is still in print today.

A Japanese diplomat, Baron Kaneko, presented the book to President Theodore Roosevelt. The president was so captivated by bushido, literally meaning “the way of the warrior,” that he purchased forty additional copies of Nitobe’s book and exuberantly distributed them to family and friends. Roosevelt was accompanied by his son Kermit during a strenuous expedition in Africa in 1909. In a letter he expressed his pride in his son’s courage and fortitude thusly: “Kermit has done particularly well. He has the spirit of a samurai!” From that beginning, samurai would over time become an everyday word in the English language.

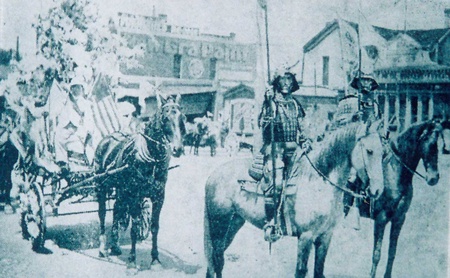

At the local level, Japanese immigrants, too, lauded the samurai spirit within their communities and to their children. There is a marvelous photograph on display in the Japanese Overseas Migration Museum in Yokohama, which shows the Nikkei community in the small mining town of Rock Spring, Wyoming, celebrating Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War with a parade in 1906. Leading the parade were two Issei men wearing samurai armor and mounted on horseback. They were followed by a horse-drawn float decorated with flowers and American and Japanese flags.

The Issei made a determined effort to nurture a positive image of the samurai in the minds of the second generation for a reason. Community leaders, teachers, and parents worried that the Nisei would suffer from low self-esteem as a result of witnessing their parents being treated as second-class non-citizens—that is, ineligible for naturalization, prohibited from owning farmland, and confined by city ordinances to “foreign” sections of town. But their samurai cultural heritage, it was hoped, would foster a positive self-image among the Nisei. And it was intended that all Nikkei, not only those of shizoku descent, would appreciate samurai ideals as a component of their ethnic character as opposed to a badge of hereditary class.

Because loyalty was the cornerstone of bushido, when applied in the right direction, the Issei saw no contradiction in utilizing the samurai code of ethics in rearing their children to be good Americans. In his book Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America (2005), Eiichiro Azuma quotes an Issei leader in Seattle who in 1938 declared that the Nisei “should feel proud for having the spirit and virtue of Bushido in their blood, that spirit which has made the country of their ancestors one of the greatest among the Nations of the World,” and that being “imbued with their ancestral ethical and loyal spirit…they are expected to be loyal and true to their country, the United States of America, the country which gave them birth, education, and protection.”

Martial arts, particularly kendo (Japanese fencing), were perfect for inculcating Nisei youth with the ideals of the samurai. In 1930 the Hokubei Butokukai (North American Martial Virtue Society) was founded as an umbrella organization for local martial arts clubs. In addition to boosting self-esteem, Issei parents saw the application of a samurai moral code as a way to exact discipline from their children and a means of curbing delinquency.

While kendo was open to both boys and girls, the most conspicuous celebration of the samurai ethos was Boys’ Day (Tango-no-Sekku). Because certain odd numbers were deemed luckier than other numbers in Japanese culture, Boys’ Day was observed on the fifth day of the fifth month (likewise, Girls’ Day was observed on the third day of the third month). Miniature suits of samurai armor and accoutrements, collectively called musha ningyō, were displayed for the occasion. Shōbu, the flower representing the month of May, was also an important part of the musha ningyō display. Shōbu is commonly translated as “iris,” but botanically it is a different plant. Its slender, curved, and pointed leaves were said to resemble the blade of a katana (samurai sword). In addition, the term shōbu is a homonym for “reverence of martial arts." Musha ningyō symbolized the warrior virtues that parents hoped their sons would grow up to possess.

To a certain extent, this sentiment has trickled down to younger generations. As a Sansei, my interest in the history and culture of Japan was piqued by discovering the samurai. I loved Kurosawa films and my fascination was clinched by the 1980 television miniseries Shōgun, based on James Clavell’s best-selling novel. I remember asking my Issei grandmother, who spoke little English, about the samurai. She replied in English with one word: straight. With her thick accent, she very emphatically pronounced it, “suto-REEEIII-to,” as if it were an example of gitaigo (a Japanese onomatopoetic “sound word”). Obviously, my grandmother wanted to project the idealized view of the samurai as being upstanding and having an unwavering moral compass.

In my mind, Darin Furukawa, a Yonsei artist, educator, and samurai arts specialist, personifies the lasting presence of samurai themes in the Nikkei narrative. He credits his parents for doing “an excellent job of fostering in [him] an appreciation of [his] Japanese heritage.” Growing up, he remembers that on a shelf in his home there were books about the Manzanar Relocation Center and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team right next to a Time-Life Books volume titled Early Japan. The design on the cover of the Time-Life book featured a samurai on horseback riding into battle, and to Darin it “was the coolest picture ever.” He earned a degree in art history from Stanford University where much of his focus was on Japanese art. Now employed by a Japan-based manufacturer of samurai armor, he can occasionally be seen strutting about Little Tokyo in Los Angeles wearing a full suit of armor during important Nikkei events, such as Nisei Week festivities.

Interestingly, the motivation of some Sansei and Yonsei to embrace the idealism of the samurai was remarkably similar to what the Issei and Nisei had done to counter the stigma of racism and discrimination before the war. In a case of history nearly repeating itself, younger generations found something in their ethnic roots that they could turn to when there was a resurgence of anti-Japanese feeling throughout the country caused by trade imbalances that strained relations between the United States and Japan. As Darin put it, “growing up in the 80s (a time when Asians were being murdered on the street because of the rise of the Japanese auto industry) the samurai, with their honor, dignity, and power, were a part of my culture that I could be proud of, even amidst the prevailing negative sentiment toward Japan at the time.”

Author and motivational speaker Lori Tsugawa Whaley is a Sansei and a self-professed “descendant of the samurai.” In her book The Courage of a Samurai: Seven Sword-Sharp Principles for Success (2015), she took Japan’s warrior ethos and Japanese American history and melded them together. Nearly all of the seven samurai principles that Lori presents in her book (courage, integrity, benevolence, respect, honesty, honor, and loyalty) are also found in Nitobe’s Bushido. But unlike Nitobe, to illustrate those principles she draws upon both Japanese and Japanese American examples, such as Michi Weglyn, Senator Daniel Inouye, the Military Intelligence Service, and the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Recent programs held at the Japanese American National Museum provide evidence of a continuing interest in our samurai heritage. One of the events was a lecture, A Samurai’s Life, which was followed by a panel discussion with members of the Nikkei Genealogical Society. A special display, Jidai: Timeless Works of Samurai Art, was co-curated by Darin Furukawa and Sansei Mike Yamasaki, the foremost expert on Japanese swords in the United States. Commenting on the programs that he and Mike have collaborated on, Darin stated, “We hope to educate and inspire the next generation to protect and preserve the history of the samurai, which, in the case of Japanese Americans like my son, is their history, as well.”

© 2016 Tim Asamen