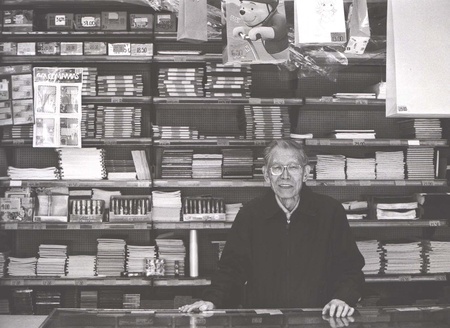

Like every morning seven days a week, Jesús Akachi opens his stationery store “La Nueva Violeta” at 9:45 in the morning sharp. Throughout the day, between notebooks, pencils, pens and thousands of merchandise that make up the items of their business, Don Jesús and his wife will serve hundreds of clients who live in the Tacuba neighborhood, in Mexico City.

The inhabitants of this place know them very well for their always friendly and attentive treatment; However, many believe that Don Jesús is not Mexican due to the oriental features of his face and the fact that his wife is Japanese. Likewise, many people do not believe that Don Jesús turned 86 years old. It seems that the harder he works, the younger he gets! It won't be until the evening, at 8:30 p.m., when he will lower the curtains of the stationery store to go rest.

How was Jesus born in Mexico? Why did he later move to Japan and witness the start of the war in 1941 and its terrible end in 1945? What was the reason for your return to Mexico in 1952? We will answer these questions.

Hundreds of thousands of Japanese began immigrating to America in the early 20th century. They were looking for a job and better living conditions that Japan was not in a position to offer them. Japanese companies recruited workers and took them to the mines, mills or plantations in America.

In addition to these companies, there were other types of organizations linked to emigration such as the Nippon Rikkokai school, founded in 1897 by a pastor converted to Christianity named Hyodayu Shimanuki. The school prepared emigrants through classes and brochures so that they would leave in the best conditions, in addition to providing them with important information about the countries to which they would go. Under the motto of “Spiritual and physical salvation of the Japanese people,” Nippon Rikkokai created an emigration office to America that allowed more than 30,000 Japanese to leave Japan, the vast majority of them to Brazil.

One of those students was Kuninosuke Akachi, father of Don Jesús, who was originally from Nagano Prefecture. Kuninosuke was born in the village of Chikuma where his parents grew rice and vegetables. Farming families in Japan at that time were very large and the income was not enough to support all their members, so the prefecture promoted a program for young people to emigrate abroad. Through an office called Shinano Kaigai Kyokai (Overseas Shinano Association), the prefecture helped tens of thousands of emigrants work outside Japan.

Likewise, the newspapers reported on the conditions and costs of going abroad. Kuninosuke's desire, like that of the vast majority of emigrants, was to reside in the United States because it was the country that offered the best salaries of all the countries in America. However; Due to the difficulties in entering that country, Kuninosuke arrived in Mexico in 1918, to the state of Sonora, when he was only 19 years old.

Kuninosuke became involved with a Japanese man named Inukai who had several ranches and businesses in that border state of Mexico, although he lived in the United States. Inukai taught him to drive a truck where he transported himself from the port of Huatabampo to Navojoa to supervise his businesses. After working for six years with Inukai, through the savings he had managed to accumulate and with the experience acquired, Akachi opened a nixtamal mill and a small raspados (ground ice sweetened with fruit syrups) stand in Huatabampo.

Kuninosuke found out that in the small town of Los Mochis, in the neighboring state of Sinaloa, there was no business of this type, so he moved to that place and very close to the market he rented a place and installed his mill. As is known, the Mexican diet is based on the consumption of tortillas, so in some years the nixtamal mill was not able to serve all the clientele who came late into the night to grind the grain to make the tortillas. .

In 1927, Kuninosuke already had the financial resources to travel to Japan and meet the young Kaworu who had already agreed to marry and come with him to Mexico. In 1930, Jesús Akachi was born in Los Mochis, the first child of the eight that the couple would have. In that same year, due to the intensity of the work at the mill, Kuninosuke's younger brother, Arata Akachi, moved to Mexico to help and take charge, in the near future, of the mill because Kuninosuke had planned to return permanently to Japan with the heritage it had gathered.

In 1937, Arata traveled to Nagano with the purpose of getting married, little Jesus accompanied him to stay and begin his primary school studies. At the end of that year, the Akachi family returned to Japan and settled in Tokyo where Kuninosuke bought land and built 34 small rooms that he put up for rent.

For Jesús, his life in Japan was not easy because although he spoke the Japanese language in Mexico with his parents, he did not have enough vocabulary to communicate with his schoolmates, so it was necessary for him to take additional classes that his teacher taught him. he imparted. On the other hand, Jesús missed the streets of Los Mochis where he walked all day long with his little friends and attended the fairs and amusement rides that were set up in the town.

However; The worst for the Akachi family was coming in those years. Although the Pacific War had not yet begun, food and other products were already rationed and the government was increasingly involving the population in the war against China. Jesús perfectly remembers how, in the company of his schoolmates, he went to the train station to say goodbye with flags and songs to the troops who were heading to the battle fronts.

When the Japanese navy attacked the Pearl Harbor naval base in December 1941, Kuninosuke knew that Japan was in grave danger because he knew perfectly well the power and wealth of the United States, an opinion that he could not share for fear of being accused of being a spy or traitor. Nor did he comment on the place where his children were born for fear of reprisals from the ultranationalist sectors of society.

At the moment when North American aircraft began to bomb large cities like Tokyo, the life of the Akachi was completely transformed. The capital was completely destroyed in March 1945 by North American aviation, which dropped the largest number of napalm bombs in all of World War II, leaving nearly 100,000 people dead. The homes that he rented and on whose income the family lived, were demolished to build a large trench that would prevent the fire from spreading to the important train station, adjacent to the homes, in the event of a bombing.

Given the great danger represented by living in Tokyo and other large cities that were targets of the bombers, the government decreed the mandatory departure of children between the third and sixth grade of primary school to rural areas. The Akachi family moved to live in Chikuma, at Kuninosuke's older brother's house.

In that town, Jesús enrolled in high school. By then the students had to collaborate in the war effort; The school days were combined with visits to the daikon (white radish) fields where the students helped in the harvest. Jesus and his companions also participated in the construction of a large secret building under the mountains where the Matsushiro Underground Imperial Barracks would be installed, near the city of Nagano, where the emperor would take refuge and the high military commanders would direct the war.

In Mexico, Arata Akachi, who was still living in Los Mochis in 1942, had been forced to concentrate in Mexico City by order of the government of President Manuel Ávila Camacho, like all the emigrants who were outside the cities of Guadalajara and Mexico. Arata, who had been in charge of the nixtamal mills in Los Mochis, had the opportunity to rent them during the war, income with which he survived and managed to open a stationery store called “La Violeta” in the Tacuba neighborhood.

In this neighborhood, the large group of emigrants that gathered established their own businesses such as auto parts stores, vulcanizers and grocery stores. Over the years, the stationery store became one of the most important businesses in Tacuba due to the attention of Arata and his wife as customers always found everything they needed.

In Japan, at the end of the war, the situation of misery and hunger worsened. Jesus and his family stayed in Chikuma because at least they had something to eat. Upon finishing his secondary studies, Jesús' desire was to continue preparing and enter the University. With that purpose he went to live in Tokyo where in addition to studying, he worked to support his studies and help his family.

The conditions of poverty and hunger were so serious that a series of diseases such as dysentery, cholera and tuberculosis spread. The latter was the one that caused more than 100 thousand deaths annually starting in 1947; Jesús acquired tuberculosis and his physical conditions prevented him from continuing his studies at the prestigious Waseda University to which he had managed to enter. Faced with this situation, he had to return with his family to Nagano to convalesce from the illness for months.

Arata proposed to his brother that Jesús return to Mexico to help him run the Tacuba stationery store and the Nixtamal mills that he had in Los Mochis. Thus, Jesús and his younger brother, Francisco, requested entry to their country of birth in the year 1952. With the help of Arata, the brothers were able to cover the expenses of the trip and began to work intensely in the stationery business as usual. supervision of the nixtamal mills in Los Mochis. At that time they introduced a machine to make tortillas, their sale was a success to the point that a ton of nixtamal was used a day to supply the great demand they had.

In 1962, Jesús married a young Japanese woman from the Nagano prefecture who moved to Mexico where they had three children. In addition to his work in the stationery store and in the mills, Jesús became decisively involved in the activities of the Nikkei community. He actively participated in the consolidation of the school that the Japanese community opened in the Tacuba neighborhood so that the children of the descendants could be better prepared and committed to the country in which they were born. Jesús' children attended that school until it closed with the creation of the Liceo Mexicano Japonés in 1976.

In addition, Jesús has been president of the Mexico-Japanese Association and of the association of the prefecture where his parents were born, Nagano kenjinkai. Jesús Akachi is one of the Japanese descendants who knows the most about the history of emigration to Mexico, which is why he participated in the preparation of the Encyclopedia of Japanese Descendants in America , a book that was published in the United States. The Nikkei community and the Tacuba neighborhood in Mexico owe a lot to Don Jesús for his contributions and service to them. Personally, I owe a debt for his teachings on the history of the Japanese in Mexico and Japan.

Author's note: On December 16, 2016, Jesús Akachi died. With him, “The new Violeta” closed its doors permanently.

© 2016 Sergio Hernández Galindo