After starting to cook in a slightly more conscious manner (living with Bia, my girlfriend, I’ve naturally left behind those university days when I thought that adding garlic to the Fugini tomato sauce was a great culinary feat), I began shopping weekly at the street market in my area, thinking a little about my physical health and a lot about my financial health.

Born and raised in a typical Japanese–Brazilian family in the interior of São Paulo, for a long time my culinary repertoire consisted of Japanese recipes living in perfect harmony with genuinely Brazilian dishes, such as beans and fried yucca (beans and Japanese rice, accompanied by misoshiru; I’ve never found that weird). As a result, my culinary vocabulary was also formed by a mix of words and concepts in both Japanese and Portuguese (for instance, fried yucca was called yucca tempura).

During these trips to the street market, I rediscovered many of the leafy vegetables that had been part of my meals at both my mother’s and my aunts’, and which are hardly ever found in the supermarkets or farmers markets in this city. I often buy chingensai (Chinese cabbage) and karashina (mustard leaves), and when buying turnip or radish I always ask for the leaves not to be removed so I can make tsukemono (pickled vegetables).

It so happens that until the time I left my mother’s house, I never thought that one day I’d be going to the street market to buy turnips, let alone that I’d be asking the merchant, “Please, don’t remove the leaves because I’ll be using them to make tsukemono.” I certainly had no interest in learning to make tsukemono during my adolescence. So, in order to learn how to prepare these dishes, there’s nothing more obviously necessary than talking to the person who taught me how to savor these dishes. After going to the street market became second nature, the frequency of my calls to my mother at dinnertime increased considerably.

But to call my mother, I need to set aside some time for it (a friend has referred to her as “a Japanese mamma”). Half an hour, at least. And on a weekday, half an hour (or more) before we begin preparing dinner is a considerable amount of time when one takes into account that we don’t get home very early. So I often go to google.jp to find out how to prepare these recipes.

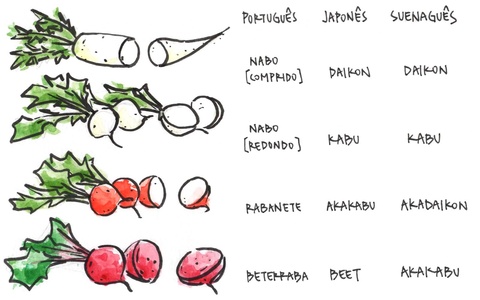

While doing various searches, I struggled with a linguistic question I’d had during my childhood/adolescence. In the Japanese–Portuguese culinary vocabulary, I was taught that daikon = long turnip, kabu = round turnip, akadaikon (literally, red daikon) = radish, and akakabu is literally, red kabu. I’ve always found these names incoherent; after all, the akadaikon looked very different from the daikon and much closer to the kabu. Radishes were much more deserving of the moniker akakabu than akadaikon, the dissonant element in that grouping.

This week, during one of these recipe searches on google.jp, I tried to find some use for the beet leaves. And I looked for akakabu leaves. And then, gee, a string of radish images popped up. I dug deeper into my research and discovered that in Japan beet is known by its English name (or bítsu, as pronounced locally).

This fact made me wonder whether calling beet akakabu was one of the many adaptations Japanese immigrants came up with while trying to establish their culture in this very different land. I’ve always found the hanaume story intriguing; in the absence of ume (Japanese plum) here in Brazil, hibiscus sepals (or roselles, or purple okras…) became substitutes for the traditional pickled dish found in Japanese cuisine. I wondered whether the beet/akakabu name adaptation was the result of similar circumstances, an impromptu improvisation of almost a century ago that here ended up as part of the language of the Japanese community. Imagine the situation (in Japanese): “So-and-so-san, you also planted that round vegetable…which looks like kabu, but it’s red all over?”

Or was it simply a linguistic workaround that the Suenaga family came up with?

Who knows?

© 2016 Nilton Suenaga