Can you talk about your own path to becoming a teacher?

My path to becoming a teacher is not a straight one. I watched how my Mom worked hard and thought constantly about her students and how to teach them best. And based on that role model, I vowed never to become a teacher! Seriously, what kind of person would put themselves through that!

I took sciences at University of British Columbia, but after flunking out in my third year, it was pretty obvious that sciences were not a good match for me. I worked for a year and then went to Douglas College which I loved. I transferred to Simon Fraser University (SFU) and was completing my English degree when the registrar told me the course I wanted was full, but if I took Children’s Literature in the Education faculty, they would give me the same credit. I really enjoyed that class, and the professor wrote a recommendation that allowed me to enter the PDP (Professional Development Program) teaching programme at Simon Fraser University. My mom always thought I’d become a teacher, but it was kind of a fluke I became one.

I owe a lot to teaching, and teaching in Coquitlam in particular. I live in Coquitlam. I met my wife in the Coquitlam district, and my daughter, Beth, attends high school in the Coquitlam district. A lot of my friends work in the Coquitlam district.

Over my 27 years of teaching, I have had great variety of roles, challenges, and rewards. I’ve taught grades 2 to 7; specialized in Music, Technology, and Gifted; worked as a Literacy consultant; and worked for the district investigating and sharing innovation. And working with kids is so great! They make me laugh and think every day.

To back up a bit in my own thought process I remember somebody in the Japanese Canadian (JC) community sending me a clipping of a profile of you a decade or so ago when you were awarded the General Governor’s award. Can you please take me to that time in your teaching career and why you designed that unit on learning about JC internment?

Getting involved in doing the Japanese Canadian resource was a funny turn of events too. I was teaching grade 4 and 5 at the time. Mas Fukawa got a grant to develop Rick Beardsley’s resource for teaching the internment to high school students, and was interested in developing a resource aimed at elementary students. Mas was working with my friend Pat Tanaka because they had developed a different project together before. Pat invited me to meet Mas so I could do maybe the desktop publishing for this new project. I was listening to them talk and what they wanted to achieve. I had just created some general lessons on social justice for my class and shared them with Mas and Pat, and we went from there. I ended up writing the lessons, and Mas and Pat developed the support pieces such as finding photos and educating me on what happened to the Japanese Canadians.

I mentioned before that I didn’t know much about my family history, but Mas was an excellent resource. She had this incredible library of photos, books and documents in her basement. We’d drink green tea and eat the curry that her husband Stan would get, and she’d school me on internment 101. It was a pretty great way to do things.

What is your own personal philosophy about teaching? How does this connect with teaching about the JC experience and being JC?

My personal philosophy about teaching is that teaching should be personal. I know that sounds redundant and circular, but I think that learning should be personally relevant to students and teachers.

In order for the content or issues to mean something to students, they have to be able to connect and relate to it. How do you get ten year-olds to understand something as important and complex as the internment? The lessons use a series of simulations that teach students what it is like to be an immigrant, what happened to Japanese Canadians, what the living conditions were like in internment, why redress and making an apology are important, etc.

Can you go into some detail about the process of outlining what you wanted to cover in that unit and how you went about creating it? What were the main points about Internment that you wanted to share? How well did your students ‘get it’?

When I started to develop the lessons, I knew I wanted them to be hands-on, minds-on, and hearts-on. I didn’t want the internment lessons to be a series of lectures or worksheets. I wanted the students to DO things. The simulations and the role playing are examples of the ‘hands-on’ parts.

For ‘minds-on’, I wanted students to THINK and be critically engaged so, for example, in one lesson, they have be figure out what is going on by being picture detectives and look for clues of what happened at Hastings Park where hundreds of Japanese Canadians were held (in the animal pens of what is now the PNE) before being shipped off the coast. In another lesson, students in groups take on the persona of say an 18 year-old boy and their group has to come to consensus of what they would pack in their suitcase if they were put in internment.

For the ‘hearts-on’ component, I wanted the students to FEEL something. We use lots of discussion and reflection so that students have a chance to relate the events and the issues as if it were happening to them. We mark off on the classroom floor how big an internment shack was, and we get them to bring in their suitcases with their belonging, and we try to fit everything in the floorplan. We read or listen to first person accounts of people who were interned or relocated to get a sense of what that was like. I can tell you the students do “get it.” Because of this emotional connection to the issue, the discussions can get very passionate, but even the quietest students show the depth of their understanding in the continuous journaling process.

Also, one of the lessons also focuses on the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and how Japanese Canadians rights were violated when they were incarcerated, lost their businesses and property, and were banished from the coast. For the new project I am working on called Landscapes of Injustice (led by Jordan Stanger-Ross of University of Victoria), I am developing new lessons that focus on dispossession (the forced sale of Japanese Canadian property), but we are in the process of possibly making the lessons from the previous resource available online to provide a larger context to the internment issue.

Did other teachers pick up on these lessons at your school? School boardwise? In the greater community?

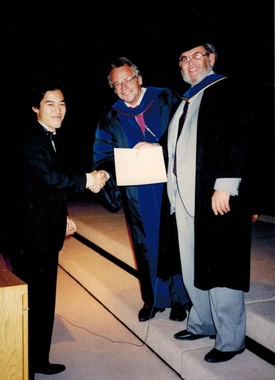

When we first developed the lessons, using the grant money, Mas sent them to every elementary school in British Columbia (BC), (the secondary resource went to every high school too). Adoption of the lessons was hit and miss, but I did numerous workshops throughout the province. When the unit received the Governor General’s Award for History in 2006, it received a lot of press and the board formally recognized me at one of their meetings.

At the time, I was working as a district resource person, so I was able to help implement the internment resource in a few schools.

For those of us in other provinces, can you talk about how the BC Social Studies curriculum is worded and what entry points there were for you to discuss Japanese Canadian Internment during World War Two? The Ontario Grade 4 and 5 expectations don’t offer much opportunity for a discussion about JC internment.

It’s funny how things cycle. In the early 2000s, the internment unit was a perfect fit for grade 5 Social Studies in BC which included immigration and social justice issues. When the curriculum changed in the later 2000s, the perfect fit disappeared and most teachers dropped the internment issue from their classrooms. But now, with our revised curriculum for 2016, it is again a good fit for grade 5 Social Studies. These critical social justice issues have returned to the curriculum. I was able to support five different classrooms this year in implementing the internment unit back into Social Studies.

How attuned is the BC curriculum to JC history and offering opportunities for it to be taught in classrooms across the divisions? From a Nikkei point of view, do you see any required changes needed?

The revised Social Studies curriculum for grade 5 is very promising in terms of teaching about the treatment of Japanese Canadians during the 1940s. Three of the four ‘Big Ideas’ in grade 5 Social Studies are related (the fourth is about resources):

- Canada’s policies and treatment of minority peoples have negative and positive legacies. (The ministry gives examples of past discriminatory government policies and actions, such as the Head Tax, the Komagata Maru incident, residential schools, and internments.)

- Immigration and multiculturalism continue to shape Canadian society and identity. (The ministry specifies topics such as: changing government policies about the origin of immigrants and the number allowed to come to Canada; and immigration to BC, including East and South Asian immigration to BC.)

- Canadian institutions and government reflect the challenge of our regional diversity. (This ties in well with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.)

From a Nikkei point of view, I guess I would like to see more direct emphasis on Japanese Canadian history, but from an educator’s point of view, I believe in the autonomy of teachers to pick issues they and their students are most passionate about within the curricular framework because that passion usually produces the best learning.

As you are teaching Grade 2 now, how are you incorporating JC history in BC in your program? Is it challenging? How do the students respond to our stories?

Yes. I started my teaching career with primary, then taught grades 4 to 7 for ten years, and now I am back in primary again. I don’t teach about the internment to my grade 2s, but I was able to team teach with three of the grade 4/5 classes in my school about the internment which was very exciting because I hadn’t taught it in so long. With the grade 2s, it is all about community, but we can work in lots of different facets of community that relate: roles and responsibilities of everyone, family histories, multiculturalism, etc. At the grade 2 level, some of the most important concepts are fairness for everyone, and working together so we can do our best and be our best. Those ideas aren’t really curricular, but I tend to emphasize these Social Responsibility concepts when we learn about community.

I’m curious to know if there was any backlash to this initiative and what it might have been in regards to?

I have received no backlash in teaching Japanese Canadian history from students and parents. Usually, I have a strong relationship with my students and parents before I begin teaching about sensitive topics. Given my personal history, I am also up front about my biases, and bias is important for students to consider when learning about any kind of history.

Once in a while, a student will say, “Weren’t we at war….” or “When you compare this to what they Japanese did to the Chinese…”, and I will remind them that we are talking about what Canadians did to other Canadians. If we are a just, free, and tolerant country, then how could we do this to our own people? Parents have been really supportive, and they come from a place of interest and wanting their children to think about these bigger ideas.

Apart from this, the only “backlash” I have received has been from other teachers. They tell me that they are interested in the topic and think it is important, but they are uncomfortable with the content and they are afraid to get it wrong. I have seen the same discomfort with other controversial topics including LGBTQ and Residential School issues. With the previous internment lessons and with the upcoming educational resources for Landscapes of Injustice, I am happy for teachers to use the resources to get the conversations (and the thinking) started.

Can you tell us a bit about the student body at your school? How diverse is it?

My school, Leigh Elementary in Coquitlam, is fairly diverse. In the last couple of years, I had a number of languages spoken at home and different ethnicities. Some of my previous schools have been far more diverse either in terms of the number of new English language learners, or just a wide range of places around the world represented in my little classroom. At my previous school, my class realized that we had six of the seven continent represented (though we don’t get a lot of students from Antarctica in BC).

Do you see the need for a national agenda regarding the teaching of the JC Internment experience? Is this part of the focus of the University of Victoria’s (BC) project “Landscapes of Injustice”?

Yes, Landscapes of Injustice would love to open a national discussion of the Japanese Canadian internment experience. As I develop new material for Landscapes, I’ve been checking different provincial curricula.

Norm, you’ve remarked at the gaps in Social Studies curriculum with respect to Nikkei history across the country. I actually thought Ontario’s was better than others in this regard because at the elementary level in other provinces, there is little attention to the internment, nor immigration and human rights for that matter. Doesn’t Ontario include concepts such as interactions and interrelations between groups, and rights and responsibilities? (www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/)

For Landscapes, I hope to incorporate some of the previous lessons, but I also want to develop some new material which takes advantage of the vast scholarly research available to us from the Landscapes network. We have professors and grad students compiling mountains of internment and relocation data from Land Titles and Government Records in the 1940s, digital maps from the GIS Mapping group, and the Oral History “cluster” is documenting interviews from internment survivors. I am co-chairing the Teacher Resources cluster with Mike Perry-Whittingham who is in charge of developing the high school lessons using the primary sources.

Do you have anything to say about the importance of the national JC community of teachers to teach its stories too?

It is SO important for Japanese Canadian teachers to tell our story.

I was talking to a historian who told me that the treatment of Japanese Canadians during World War II was a pivotal Canadian human rights issue that helped to push Canada to adopt its own Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and it was the Redress movement that was the first big test of the strength of the Charter.

We need to keep this history alive, especially as time goes on and we lose more and more of the voices of that era.

My students go home and they talk about the internment and they educate their parents, many of whom had no idea that it had happened. I have to say I learned more about the internment from Mas and researching for these lessons than from my family stories or from my own education. I’m not alone in this. This year, I met an Ontario teacher who learned that her father was interned because she came across his picture in a book on internment!

As Canadian Nikkei teachers then do you see a particular responsibility being placed on us to teach JC history and make sure that it is included in the curriculum?

I would love it if Nikkei teachers across the country would teach more Japanese Canadian history, but I am also realistic. If it had not been for Mas Fukawa and Pat Tanaka, I probably would not have taken such a keen interest in having the Nikkei story told. I was lucky enough to have a couple of angels sitting on my shoulder to tell me to go for it. Yes, I would love it if Nikkei teachers would champion the Nikkei story, but I find it encouraging that even non-Nikkei teachers see our history as an essential part of Canadian history.

For more information about the Landscapes of Injustice project and Japanese Canadian history:

- JapaneseCanadianhistory.net

- Landscapesofinjustice.com

© 2016 Norm Ibuki