In 2016, how does one go about learning to be Nikkei and more to the point of this interview, teach it? On the drive into school this morning I heard two reports on CBC news that were disconcerting: one about a public opinion poll that found that almost 70 percent of Canadians believe that immigrants need to be “more Canadian” (whatever that might mean?), the other about anti-Semitism. Then I get to school and talk to a rather condescending resource teacher who remarked that “‘Norm’ is a lot more common than ‘Ibuki’” (then I helped her with the pronunciation of it saying it sounded like “Suzuki”) when we were introduced. I felt like I was back in the 1970s.

If, like me, you are now middle age and grew up in a suburban cultural vacuum that was well away from anything dangerously “Japanese” then you may have had to go to some distance to find answers to your own Nikkei identity.

Like British Columbia teacher Greg Miyanaga, I grew up around relatives in Toronto and Hamilton. We attended annual Toronto Japanese Canadian picnics and had a good relationship to “Japan” as Mom always had friends (usually visiting scientists, business people or farmers) and even hosted exchange students in the 1990s.

My Nisei parents always valued education. Mom was proud of the fact that she finished high school (Westdale Collegiate in Hamilton). Dad joined the Canadian Army once he could. Even though we didn’t go on many vacations or have a lot of material stuff, we four kids had enough and they helped us all through university and beyond. We kids always worked hard to get what we wanted and are now grateful for those values that they instilled in us. Money can’t buy that.

I went to Ryerson for journalism and never saw myself ever being a school teacher until later. A few relatives were/are teachers. While living in BC I became a teacher specializing in English as a Second Language. This led to working in Japan for nine years. I returned to Ontario where I’ve taught in the public system for the past 11 years.

Today, in our multicultural society and 71 years after the end of WWII, I would have realistically expected that students would be learning something about the internment of Japanese Canadians (JC) but they don’t. Just as Canada has not seriously addressed the needs of its indigenous people who still cry for justice over issues like murdered and missing First Nations women and the shameful legacy of residential schools, dealing with the legacy of JC internment remains unresolved too on many fronts.

I used to remark about the need for young Nikkei to learn about their history which remains as important as ever. Unfortunately, that imperative never caught on in the wider community so I am not surprised to now be hearing more and more about young Nikkei kids who don’t know anything about their family experience in Canada.

So, I wonder, as parents or grandparents, how much does it in fact matter that our JC stories are passed onto future generations?

Furthermore, have you ever asked your teacher, your child’s teacher, school trustee, or local board of education to include the JC experience in their social studies or history programs? When it is Asian Heritage Month (May) at schools have you ever lobbied to have names like Dr. Tom Shoyama, Joy Kogawa, and Art Miki included?

BC teacher Greg Miyanaga of Coquitlam, was awarded a Governor General’s Award for Excellence in Teaching Canadian History in 2006 for designing a Grade 5 unit about the Internment.

Nowadays, besides teaching, Greg is a member of a group of teachers and academics headed by University of Victoria BC professor Jordan Stanger-Ross called “Landscapes of Injustice”, a seven-year, multi-partner research project exploring the forced dispossession of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War that is being led by researchers at UVic with 13 partner institutions.

The project has received a $2.5 million partnership grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and partnering institutions have committed an additional $3 million. Landscapes of Injustice will develop education materials, publications, public events and culminate in a cross-country tour of a new interactive museum exhibit beginning in 2019.

(I’d like to humbly dedicate this interview to the first JC to become a certified teacher in BC, Dr. Irene Ayako Uchida [1917-2013], who went from being the principal at the Lemon Creek internment camp school to being a world renowned geneticist, and to the many who followed in her immense footsteps. We all make a difference.)

* * * * *

First, your family is still in British Columbia. Can you tell us a bit about your family history pre-war, during the internment years and post-WW2? What was the journey back to the coast like? Where did both sides of your family end up settling?

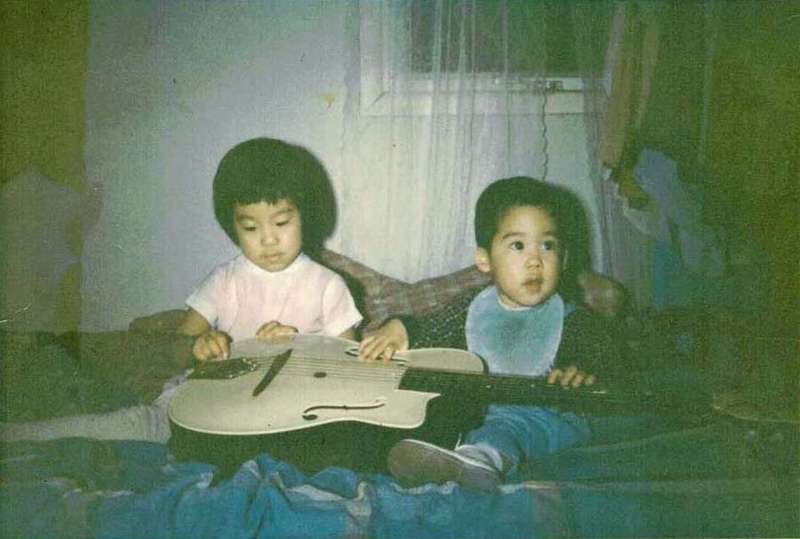

I actually don’t have a strong sense of my family history. My family did not really talk about their early lives, but when I was a child, once in awhile, with my grandparents broken English and our non-existent understanding of the Japanese language, my sister, Marlene, and I could get a sense of what happened in our grandparents’ lives.

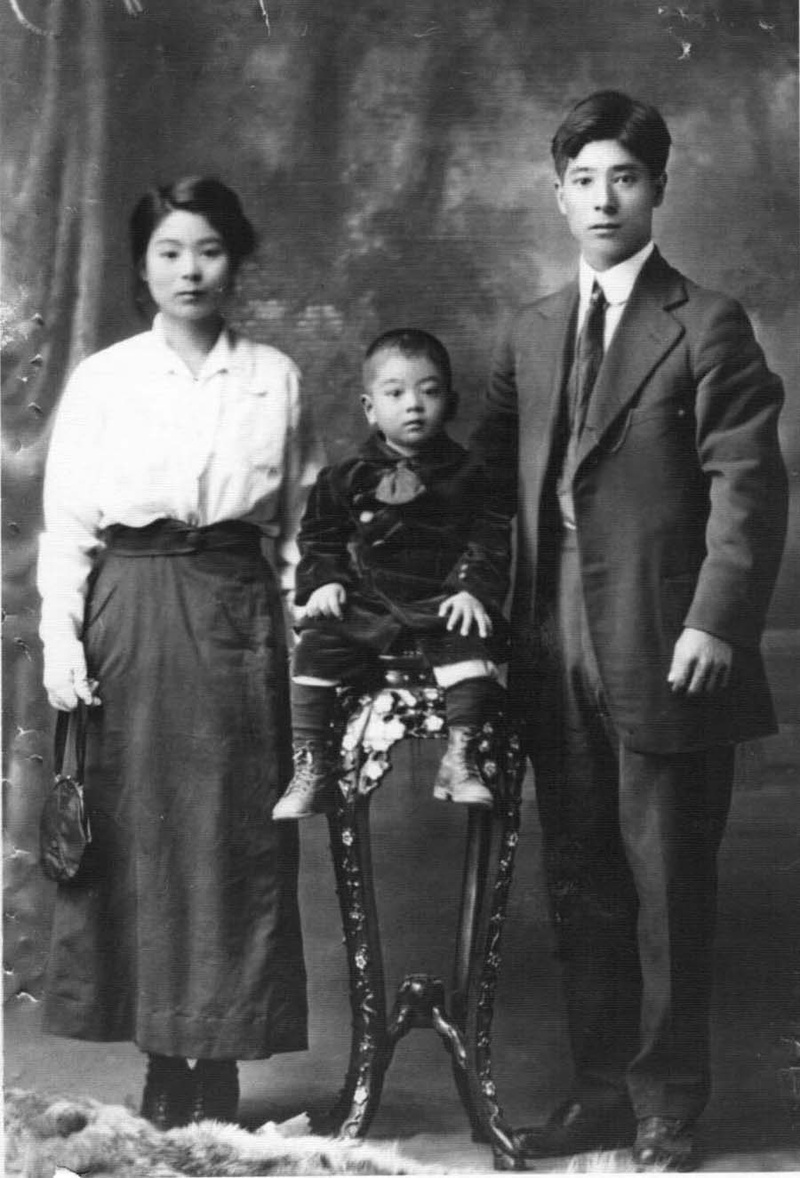

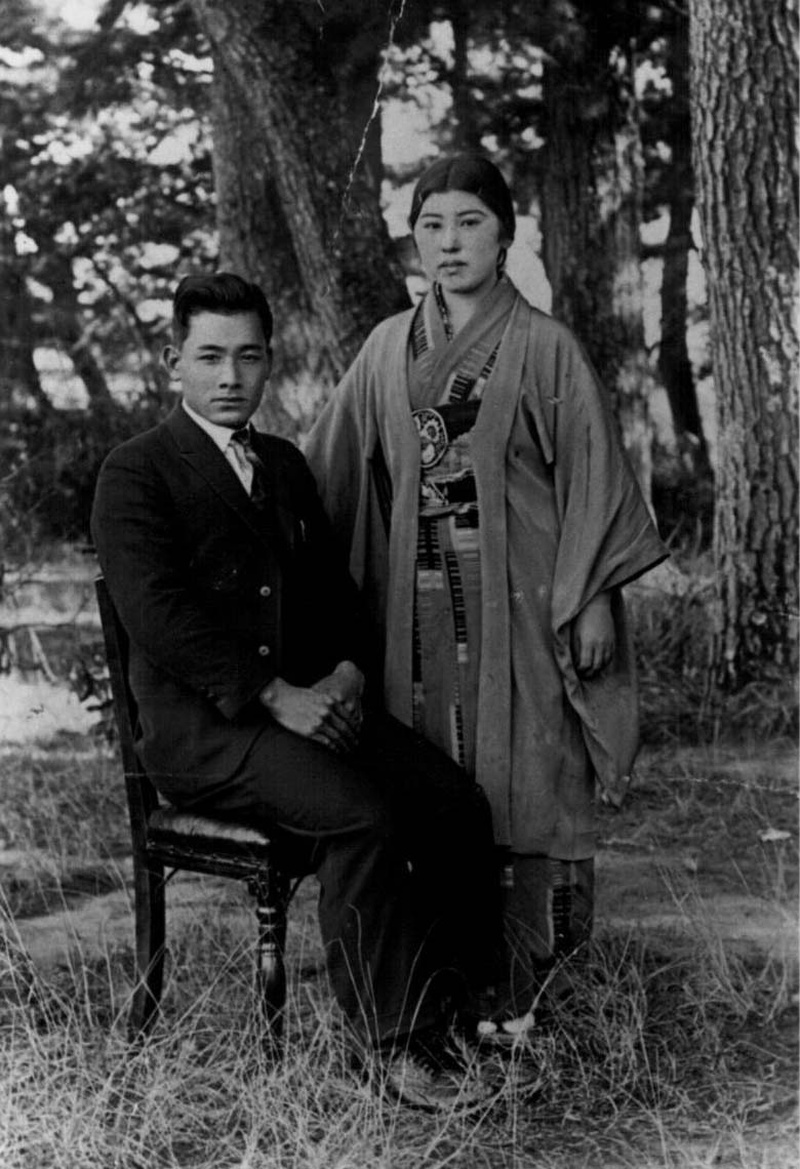

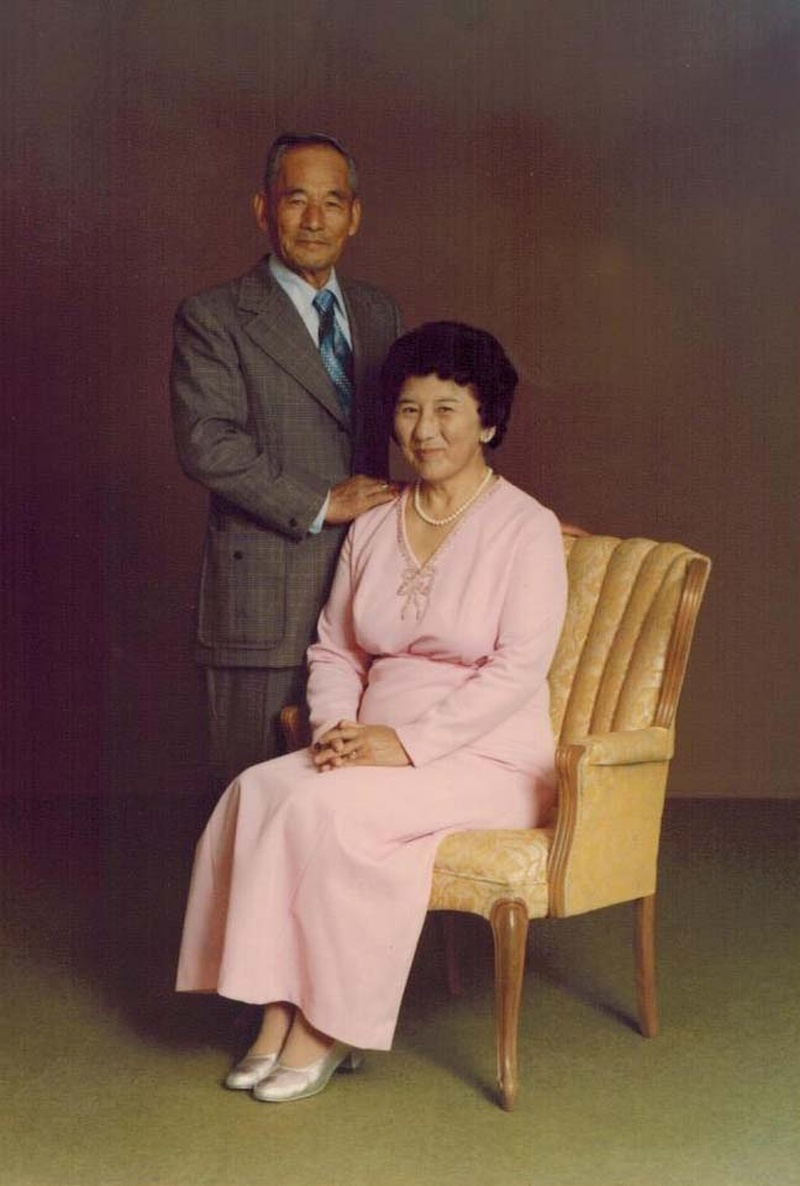

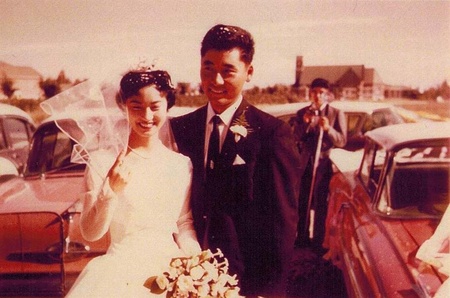

My grandfather, Yoshihiko (Joe) on my dad’s side, used to tell us that he came to Canada when he was 17, he had little money, and no friends, but he did have a blanket! After working for a bit, he went back to Japan, married my grandma, Kii, and came back to Canada to settle in the Mission area (east of Vancouver). That is where my father, Tom Miyanaga, was born, as well as my uncles, Bob and John. My grandfather worked in logging and eventually started his own company.

When Japanese Canadians were forced away from the coast, the family lost everything. They ended up working as hired hands on the sugar beet farms of southern Alberta. My father was only 6, but he remembers how cold it was. (My aunt Rose was born in Lethbridge in 1944). At first, it was hard, but they established roots there and ended up staying in Taber after the war ended.

My grandfather started his own farm, Miyanaga and Sons, and though it took a long time, it became big and successful. My uncles, Bob and John, ran it, and my cousins, Mark, Jay, and Jordy, still run it today which is pretty great to have three generations of a family business. My father worked on the farm, but went away to the University of Alberta and became a civil engineer.

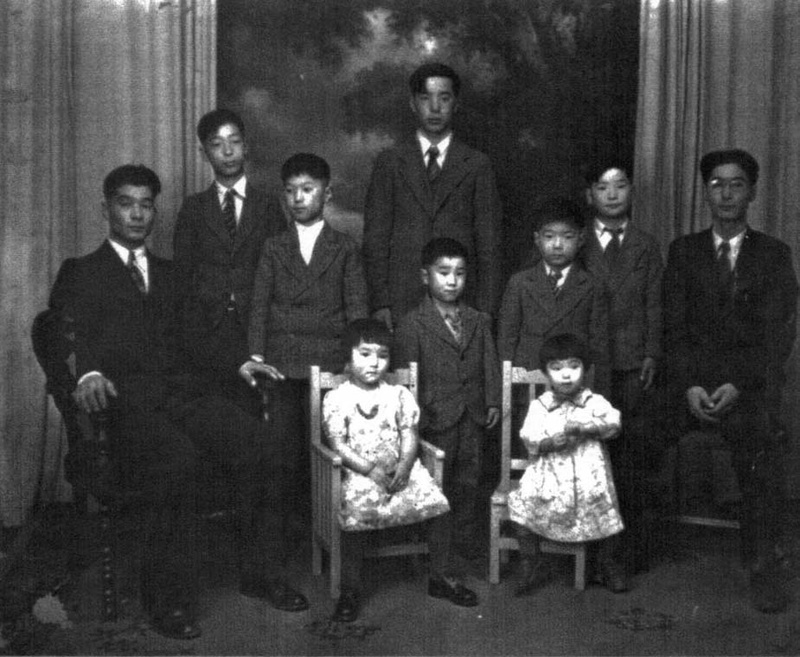

My mother Eileen’s family came from Okinawa, and my grandfather, Shinei Higa, came to Canada in 1917 to join my great grandfather who came a few years before and was working as a labourer building the CPR line. My grandfather then worked in coal mines in Hardieville, and sent for my grandma, Uta, to join him from Japan. Later, they went to work on farms in southern Alberta. If my father’s family had not been relocated to Alberta, he might not have met my mom, and I would never have been born!

An ironic aside is that some of my mom’s brothers served in the Canadian army while my dad’s side was being relocated. Mom’s brother, my uncle Harry, served overseas in Britain, France, Holland, and Belgium. When he came back to Canada, he brought his Scottish war bride, my aunt Jessie. According to Mom’s recollection, my uncle, George was conscripted and went to India and Nepal.

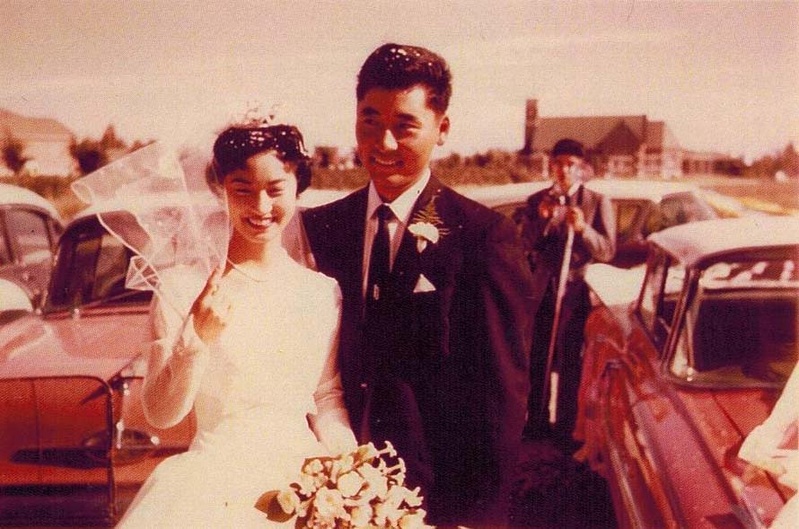

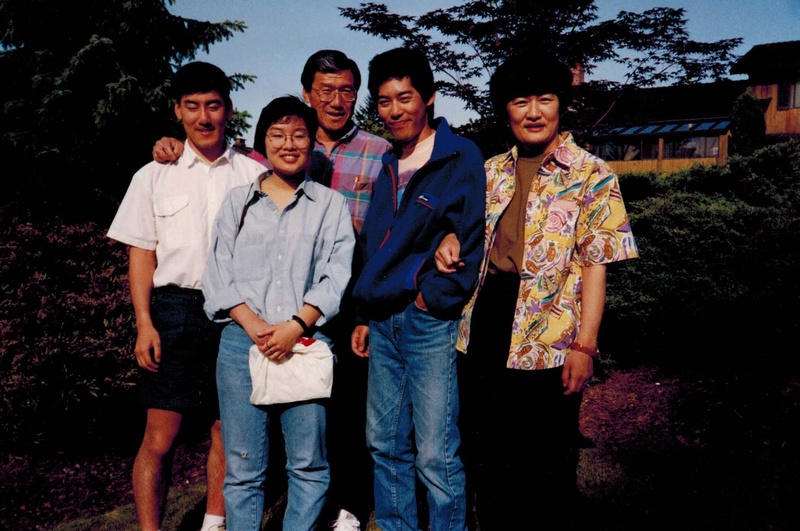

My father, Tom, was a city engineer in Medicine Hat where my sister and I were born. We lived in Lethbridge until I started school, and then on my sixth birthday, we moved to BC in 1969 when my dad was transferred to the coast. My dad, especially loved the coast because of the fishing, the water-skiing, and the mountains. My mom was happy to move to the Vancouver area because her sister had moved there before us.

Many of us middle-aged Nikkei share much of what you shared here: parents that didn’t tell their kids much about their internment experience, losing family farms and property and being exiled from coastal BC. How do you understand the reasons for this in your own family?

My aunt Rose explained it to me:

I did talk about the relocation with grandpa and grandma. Their attitude toward what had happened was solid and unwavering. They said that in times of war, governments have to do what they can to protect their country and its citizens. They thought the government was within their right to do what they did.

What I am most appreciative of is our parents never talked with resentment or bitterness about what had happened to them. Instead they talked about making the best of what is, working hard and moving forward. Parents as the most important models for their children could easily fill their children's minds with a lifetime of negative feelings of resentment.

This makes sense to me in the context of my grandparents. They were forward-thinking, optimistic people. They NEVER complained about anything in front of me. Maybe as farmers it was a professional necessity to be patient optimists. Beyond “shikata ga nai”, I could see them consciously not passing on that negativity to the next generations.

You mentioned that your mother and other members of your family are teachers. Can you talk a bit about your family’s connection to teaching?

Yes, I come from a long line of teachers. Or maybe that is a WIDE line as we packed a lot of teachers into two generations.

My mom’s side of the family is huge! There were fourteen children. My mom, Eileen, and her sister, Judy Mukuda, are retired teachers from the Coquitlam school district. My mom taught primary grades and learning assistance. My aunt was the ESL coordinator for the district. Another of my mom’s sisters, Geri Miyashiro was a teacher in Taber (Alberta). Taber is small so she ended up teaching cousins on both sides of my family. Also, on my mom’s side, my uncles George (who got his degree when he was 50) and Sam were teachers in Alberta, and my cousins Terri and Brian Thorlacius are music teachers in Calgary. I have a few other cousins, Lorraine, Jennifer and Frank who are or were teachers also. Once, in grade 7, my mom was taught by her brother Jack’s fiancee who later became my aunt Amy.

On my dad’s side, my aunt, Rose Oishi, taught primary grades in Edmonton, and her husband, Gil, was a high school principal and later an administrator for the JET program. My wife, Brenda Miyanaga, is a teacher in the Coquitlam school district like me, but she teaches Kindergarten.

How did being Nikkei affect your Mom’s or any other family members position as teachers? How did this impact the community’s understanding of JCs and our history in BC?

I asked my Aunt Rose about this and she replied:

Being a Nikkei didn't seem to affect my position as a teacher in Edmonton. Perhaps because of the diverse population in Northern Alberta there wasn't any obvious concern about my ethnicity. Also, the parents of the children I taught were highly educated and of high socio-economic standing and their concerns were about a sound education for their children. The internment history never came up in my teaching career other than from curious co-workers or some parents. These occasions were very rare.

© 2016 Norm Ibuki