Since around 2000, Latin American countries have been attracting attention for their high economic growth rates, and the consumer market of the new middle class has become the focus of global attention. International prices of primary products such as oil, mineral resources, and grains have soared, and many countries (Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Bolivia, Venezuela, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, etc.) have had good finances and implemented comprehensive social policies, leading to the belief that they would finally be able to address structural poverty and education issues with their own resources. Of particular note among emerging countries was Brazil, which was predicted to surpass Japan's current GDP of 550 trillion yen in just 30 years (as of 2015, Brazil's GDP is equivalent to 220 trillion yen) 1 .

However, the global economic downturn that began three years ago, mainly due to the slowdown of the Chinese economy, has led to a decline in the international prices of primary commodities, which are the main export items of many Latin American countries. As a result, foreign exchange earnings have fallen sharply, and the growth model that had existed up until then has ceased to function.

In light of these circumstances, we have analysed the trends in the already low savings rates in these regions.

Like household finances, the ability of national and local governments to deal with tough situations depends on whether they have reserve funds. If there are no reserve funds when the economy is sluggish, they will fall into financial difficulties, social conditions will become tense, and political instability will occur, as in Brazil today (impeachment trials, removal of the president, appointment of an interim president, etc.). In such a situation, they will be able to borrow money only at very high interest rates. It is the same situation as when ordinary people borrow money from loan sharks on the street.

Reserve funds are low in Latin American countries, and household savings rates in these countries are generally said to be low as well. The middle class often save money for clear purposes, such as renovating or expanding their homes or stores, expanding their businesses, or paying for their children's higher education. However, because they have little trust in banks or the monetary policies of their countries, many of them keep their money in safe deposit boxes in dollars, or invest in cars and affordable real estate that can be sold at any time. The same principle applies to the wealthy, who often keep their cash and assets overseas, and store their assets in tax havens such as those that are currently the subject of much discussion due to the "Panama Papers."

According to a survey of savings rates by income bracket and gender conducted by the IDB Inter-American Development Bank a few years ago, the average savings rate in the region was around 10% .2 The highest rates were in Colombia at 15%, Bolivia at 14%, and Argentina and Uruguay, both at 13%. Looking only at the savings rates of the super-high-income bracket, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Honduras and Mexico show savings rates two to three times higher than the average. However, this is an estimate based only on available statistics, and in many countries half or more of the economy is in a shadow economy, so even if someone's income appears low, they may have hidden assets and savings. It could be said that this bracket has been driving the consumer market in recent years.

On the other hand, it is said that 30 to 40 percent of the lower middle class are unstable people who are falling back into poverty due to fluctuations in the global economy, and this is becoming a cause of social unrest. The desire to save among this group is focused on individual purposes (buying home appliances, motorcycles, used cars), and they have little awareness of medium- to long-term savings (depositing money in banks, signing up for savings-type insurance, or paying into pensions).

Experts point out that, like the middle class, the poor also save for specific purposes but rarely deposit their savings in banks. Much of their income does not come from regular employment or business, and their employers and business partners do not want to pay them by bank transfer. For example, only half of their salary is paid officially (listed on the pay slip, with taxes and social insurance deducted), and the other half is paid in cash, with no records kept in the books, and the transaction is processed as a secret. There are also often no estimates or invoices for contract fees, and everything is paid in cash.

According to a survey by the World Bank's Global Findex, only 51% of the population in Latin America has a bank account, which is considerably lower than the 94% rate in OECD countries. The countries with the highest bank account ownership rates in Latin America are Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, Panama, Bolivia, Guatemala, and Mexico, where 40% of even the poor have an account. However, these accounts are used to transfer government subsidies and family allowances for poverty reduction, and there is little awareness of managing funds. Many of the poor have little financial literacy, and have little awareness of using their accounts to save money or to take out small loans with the savings to buy home appliances. Instead, they often buy in installments at regular stores where high interest rates are added.

Meanwhile, an IDB survey has found that people who live in urban areas, are more highly educated, and have regular employment tend to have higher savings rates. Also, 70% of Bolivians living in rural areas and regional cities save a portion of their income. Other surveys have also found that women's savings contribute significantly to their children's education and family stability, leading to less wasteful spending and improved living standards.3

Due to the diversity of Latin America and its social and industrial structures, the methods of saving, their purpose, and how they are used vary by country, region, employment type, and income level, making it impossible to generalize to one set of characteristics. Currently, most countries are not in a state of inflation, except for Venezuela and Argentina (both countries have inflation rates of over 40% per year as of August 2016). In such an economic environment, savings are expected to be the greatest poverty countermeasure and one way to achieve social inclusion. However, there are still many countries with poor fiscal management, and from the perspective of ordinary citizens, saving by depositing money in banks or mutual aid societies is too risky.

People who have lived in such an environment tend to live with the same mindset even after moving abroad. Many Japanese workers of South American descent living in Japan have a strong desire to consume from the beginning, and tend to buy a lot of home appliances, furniture, cars, and clothes. When their expenses exceed their income, they often start by borrowing money from friends and relatives, and gradually turn to credit cards and consumer credit. When buying a car or a house, they often take out a medium- to long-term loan that is just at the upper limit of the couple's combined income. Because of unstable employment, if even one person becomes unemployed or unable to work for health reasons, they quickly fall behind on payments and default on their debts. In the worst case scenario, they file for bankruptcy. They have no sense of saving to prepare for such situations, and even if they sell their car, they can hardly get any cash.

The 2008 Lehman Shock dealt a major blow to the entire industrial sector. Many South American workers lost their jobs and were unable to pay their home or car loans. At the time, there were reports that about 40% of Peruvian homeowners had given up their homes, but there is no data to back this up. In any case, many people had their homes auctioned by the courts or filed for legal bankruptcy. There have also been reports of people leaving their cars in the parking lot at Narita Airport and returning to their home countries without permission, with the keys still on the outside of the house.

On the other hand, some clever dekasegi workers saved their earnings in Japanese yen and dollars, as inflation rates in their home countries were high and the currency was low in value. Some Nikkei saved in this way for four or five years, then bought several plots of land and apartments on the outskirts of Lima, and used that to build up considerable wealth and become businessmen. One couple who worked in a factory put up with living in cramped company housing, and increased their wealth by buying real estate every time they saved up tens of thousands of dollars. Some have used that money to start new businesses, while others have made huge profits from the bubble a few years ago and gained social and economic status. These are people who have made good use of the economic situation in Japan and South America.

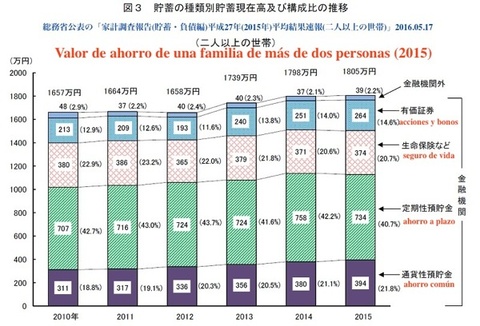

So, is Japan's savings rate high or low? Although consumption trends have changed somewhat due to the deflation that has continued for over 20 years and Abenomics in recent years, the country is caught in a dilemma where no matter how much money is pumped into the market, it cannot stimulate personal consumption. During the period of high economic growth, Japan's "household savings rate" fluctuated between 15% and 20%, so financial institutions were able to lend a lot of money to companies and the government. As a result, there was excessive consumption during the bubble period of the 1980s, but as the value of real estate gradually fell, companies and individuals who used it as collateral were forced to go bankrupt or reduce their assets. Since 1995, we have been in a state of deflation, which continues to this day. Around 1997, the household savings rate fell to 10%, and five years ago it was 2%, and in 2014 it was only 0.07%. It has been pointed out that if this continues, it will become negative due to the effects of a declining birthrate and aging population4 .

Another indicator of savings rates is the "average savings amount5 " often reported by the media, which is said to be 13.09 million yen for Japanese working households (2015). This figure is difficult for the general public to understand, but when broken down by age group, it is 1.89 million yen for those in their 20s, 4.94 million yen for those in their 30s, 5.94 million yen for those in their 40s, 13.24 million yen for those in their 50s, 16.44 million yen for those in their 60s, and 16.18 million yen for those in their 70s. However, experts also recommend using the median (the amount held by the person in the middle when arranging the savings amounts from largest to smallest) rather than the average to get an accurate idea of the savings rate6 . From this perspective, the median savings amount is only 4 million yen, and the savings of younger generations, especially those in their 40s and younger, are very low, and many people in even younger generations have no savings at all.

As you can see, Japan's current savings rate is quite low. As a result, many people are now saving more, not spending money on unnecessary things, and being very selective about their consumption, tending to value emotions, space, stories, and convenience. They also plan their lives with serious consideration for their children's education and retirement. It is precisely because of this situation that no matter how much the government tries to stimulate consumption, the younger generation and the working middle generation refrain from spending.

What should working families of Japanese South Americans living in Japan do in the future? Recently, there has been an increase in inquiries about pensions from Japanese South American workers who are worried about their retirement. However, even though they are heavily in debt, they still seem to have a desire to spend. From now on, they will need to buy what they need, not what they want, and work hard to save in a planned manner. The question for the future will be whether they can learn to live this way even now.

Notes:

1. The 2006 edition of "The World in 2050" by PwC Price Waterhouse Consulting states that the growth rate of the emerging countries known as BRICs will be remarkable, with Brazil and India becoming major powers following the United States and China, and Japan falling into a significant decline. Reference: " PwC releases research report "The World in 2050," predicts GDP of major countries - the center of the global economy will shift, but emerging countries will also face growth challenges "

2. Estudio EDISUR, “ The Newspaper ,” June 30, 2015. According to a study by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), in 10 of 14 Latin American countries, the top 20 percent of the population has more savings than the other 80 percent of the population.

3. Juan Carlos Elorza (CAF), “Ahorrar en Latinoamérica: is mission impossible? ” El País (Spain), April 19, 2016.

4. With regard to savings, there is the "household savings rate" in the Cabinet Office's National Economic Accounts and the "average savings rate" from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications' Household Income and Expenditure Survey. The former is used to find out how much of income can be saved, while the latter indicates the surplus rate of working households.

-Cabinet Office

-Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

- " Is the decline in savings rate real? " (Garbagenews)

5. This indicator is published annually by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications as the "Average Results of the Household Survey Report (Savings and Liabilities)." According to the 2015 data, the average savings for households with two or more people is 18.05 million yen. This is the total of all financial assets, including securities, life insurance, fixed-term deposits, and deposits in domestic and foreign currencies. However, if you look at this indicator for worker's households (two or more people), it comes to 13.09 million yen (2015).

6. Haji Koichi, " Should an average household have savings of 18.05 million yen or 9.97 million yen? " Nikkei Research Institute, May 2016.

He emphasizes that it will be difficult to see the true picture unless we make more use of the median rather than the average.

© 2016 Alberto J. Matsumoto