Heidi Kim is a writer, literary scholar, and editor of the new book, Taken from the Paradise Isle: The Hoshida Family Story.

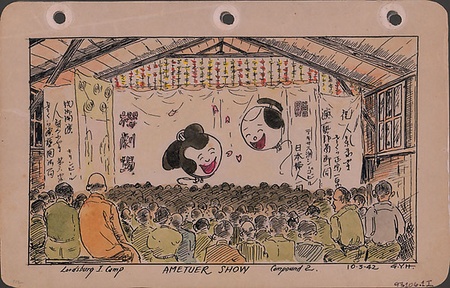

Taken from the Paradise Isle explores what a Japanese American family experienced during their separation and unjust incarceration during World War II. The book reveals its subject through intimate excerpts from George Hoshida’s diary and memoir, as well as correspondence with his wife, Tamae. Hoshida’s diary includes watercolors and sketches, adding an evocative visual element to the personal accounts.

Discover Nikkei had the opportunity to engage Kim for a brief conversation about the book.

* * * * *

DN (Discover Nikkei): Please share a little bit about who you are and your background, so that we can introduce you to our readers.

HK (Heidi Kim): I currently live and work in North Carolina, where I’m an English professor at UNC Chapel Hill. I teach mostly contemporary American fiction, usually with a historical perspective. I grew up in New Jersey and went to Harvard for college and Northwestern for my Ph.D., so I’ve lived in various parts of the country. (But I’m not from a Seabrook family! Japanese Americans always ask that when they find out I’m from New Jersey, since they know I work on the incarceration.)

DN: How did you originally become involved with this project, and what interested you about it?

HK: I first read the Hoshidas’ letters and George’s memoir at the Japanese American National Museum around 2008. What really drew me in was the exchange of letters between Tamae and George, because you can so clearly trace the dynamic of their daily lives and their emotional states in the camps. The Hawaiian story was at that time so little told (and still is, though more books have come out since) that I was also drawn in by the sheer novelty.

DN: Can you comment a bit on the book's evolution from inspiration to the completed work? For example, did you learn anything that particularly surprised you after you started researching the topic?

HK: Cutting the book down for size was incredibly difficult, and I really regret that I had to cut so much of the detail about their early lives in Hawaii—cane planting, plantation life, etc. George included a lot of loving description of the locations and events of his childhood and young adulthood. With the family’s support, I’m still trying to think of what the best way would be to share some of that material with a wider audience.

I really enjoyed following up every little piece of information that George gives. He mentions that the captured Japanese submarine attacker was imprisoned with the Japanese Americans at Sand Island. That’s true, and there’s a whole fascinating story behind that man’s life. His niece and nephew who were at college on the mainland narrowly escaped being put in the camps because their college worked out a deal to send them to Oberlin College in Ohio.

DN: The book explores events and issues of 70 years ago. What aspects do you think have the most relevance to today, and why?

HK: Unfortunately, it’s still highly relevant, as we’ve seen recently with the discussion of Syrian refugees and Muslim immigration. The whole issue of racial profiling is also highly tied to historical events like the Japanese American incarceration. I always challenge my students to think about their own ethics and what they would be willing to do or to risk.

DN: Think back to the first time you saw George Hoshida’s artwork and correspondence. What was your initial reaction? What were your initial thoughts?

HK: His artwork is beautiful. We have so few color images of the incarceration that his color drawings are immensely valuable. But what really brings the incarceration to life, for me, are his quick little sketches. These are the closest that we have to candid photos of this era, since photography was so restricted and usually posed, with film and development being expensive and difficult to come by. I still think that these are some of the most valuable documents we have in conveying what life was like in the camps.

DN: If you had to pick one idea, life lesson, or theme that you’d like readers to take with them after reading this book, what would it be?

HK: Resilience, both on a personal level and a national level. The Hoshidas rebuilt their lives with love, strength, and grace. But also, George levels some pretty damning critiques at the United States about their treatment of Japanese Americans, African Americans, and other minorities, and compares it to the fall of Rome. He ends the book happily, but the question of how the nation is going to respond still seems open.

DN: What have been some of the most interesting or unexpected comments or reactions that you have received from readers regarding this book so far? Any anecdotes that you can share?

HK: The response has been very warm. I did a book tour in Hawaii in December, and got to meet many people who knew George or Tamae Hoshida, including one woman who grew up with them on the plantation! That was probably the biggest surprise. I also met others whose families were incarcerated. That was so uncommon in Hawaii that I learned something new and important from each encounter.

The Hoshidas have been delighted, and very emotional. It’s been difficult for the daughters to read the book.

DN: Have you shared the book with any of your students? If so, did they have any interesting comments or reactions to the material?

HK: I taught the book in courses on the incarceration this past term. One really interesting reaction I got was that they really loved the relationship between George and Tamae—how strong and loving it was. One student said it was a welcome relief after the tension and abuse in Farewell to Manzanar. They were also very intrigued by the difference in how the incarceration was handled on Hawaii and the mainland, and how comfortable George is with his Japanese cultural practices and identity, compared again to someone like Jeanne in Farewell, who is always struggling with trying to look and seem all-American.

DN: What are you working on next?

HK: I need to go back to some of my academic research. Probably the next big project is on the stigma of illegal immigration as it haunted Chinese American artists during the Cold War, but I also have some more incarceration research projects in the works.

DN: Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

HK: I’m not Japanese American, and I think sometimes people of all ethnicities are surprised by that, considering that I’ve devoted so much time to researching and teaching this topic. But this is a topic that we all have to know and care about. I came to it from my interest in civil rights. I understand why people are surprised, but I wish they wouldn’t be. The question should be why more people don’t care, not why I do.

* * * * *

Author Discussion—Taken from the Paradise Isle by Heidi Kim

Japanese American National Museum

Saturday, January 9, 2016

Taken from the Paradise Isle tells the story of the Japanese American incarceration through selections from George Hoshida’s memoir, diary, letters, and artworks. These first-person sources are bolstered by extensive archival documents and editor Heidi Kim’s historical contextualization. The book provides a new and important perspective on the tragedy of the incarceration as it affected Japanese American families in Hawai‘i, adding to the growing body of literature that illuminates the violation of Nikkei civil rights during World War II.

For more information about this event >>

© 2016 Japanese American National Museum