Journalism in the Peruvian-Japanese community is almost as old as the history of Japanese immigrants itself. The need to be informed in their own language prompted the appearance in 1909, ten years after the beginning of Japanese immigration to Peru, of Nipponjin (The Japanese), the first Japanese news program in Lima.

Its preparation was rudimentary. It was written by hand on office paper (the same one used in businesses to wrap packages) and its 40 sheets were tied together with a piece of string. Once finished, the only copy was distributed among Japanese hair salons and commercial houses. First it was the turn of one business, then another, and so each business took turns reading it. In this way the news was literally passed from hand to hand. And behind this entire chain there was only one man who dedicated his own time and effort to bringing forward Nipponjin , which in one year only had 4 editions.

Nipponjin was short-lived, but it was enough to awaken the journalistic bug among the Japanese community. A year after its launch, other Japanese newspapers and news programs began to appear in Lima.

The first copy of Jiritsu (The Independent or Independence) came out in 1910. With about 70 pages per edition, it was handwritten and mimeographed. Emulating the current newspaper El Peruano, Jiritsu 's content consisted mainly of Peruvian legal regulations and consular notices, among other topics, all related to the community in Peru.

Everything was written in Japanese. With a total of 12 editions, Jiritsu 's last publication came out in 1913. In that same year, another Japanese newspaper, the Andes Jiho, made its debut.

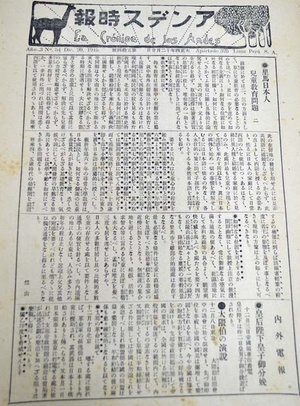

Andes Jiho (The Chronicle of the Andes) had 60 fewer pages than Jiritsu , but it came out every fortnight under the auspices of the Japanese Society of Peru. Although it did not publish photographs, its varied content made it attractive: a bit of history and geography of Peru, verses, Spanish lessons (daily phrases), local notes (such as advertisements and notices of thanks for funerals) as well as news ( although late). Thanks to a collection, the necessary machinery for printing was acquired, imported directly from Japan. The era of the mimeograph machine is behind us.

In 1921 , Andes Jiho's competition came out: Nippi Shimpo (Japanese Peruvian News). At that time, Andes Jiho represented the ruling class of the community, while Nippi Shimpo represented the rest. Until 1929, both newspapers were circulating in Lima, until a third newspaper appeared on the scene that same year, with a more neutral position. It was the Peru Nichi Nichi Shimbun (Peru Daily News).

His presentation was more modern and, unlike the other two, his news was more current, since he received it by radio and cable. But it only lasted half a year, since it merged with Andes Jiho and Nippi Shimpo to create Lima Nippo , whose first issue came out in July 1929.

But barely a month after it was launched, another newspaper appeared: Peru Jiho (Crónicas del Perú). This time, the Nisei were considered including a section in Japanese and another in Spanish. Its last publication was in 1941 when Perú Hochi (Peru Report) appeared, another newspaper in Japanese. But it was also in circulation for a short time, just half a year. The censorship policies and the atmosphere of war 1 that was felt in Peru closed all the community's media, causing a journalistic silence between 1942 and 1950.

NEW STAGE AFTER THE WAR

In 1950, the community's oldest newspaper, Perú Shimpo (New News of Peru), appeared almost by chance. It is said as an anecdote that before founding Perú Shimpo , its promoters were thinking about whether to open a marriage agency or a newspaper. “We have to do something for the colony” they said. Happily they decided on the latter.

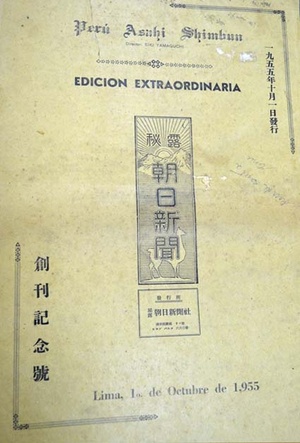

Almost simultaneously, between 1955 and 1964, Perú Asahi Shimbun (La Aurora del Perú) circulated, also in a bilingual edition, but with a short existence (9 years). Instead, Peru Shimpo continued on the path, to this day. In 1981, Prensa Nikkei joined the written information work, with content entirely in Spanish on news from the Japanese and local community and from Japan.

The printed journalistic format was not only limited to newspapers. By the end of the 1950s, magazines such as Puente, Superación, Juventud Nisey, and Nikko appeared. and Sakura , which were widely accepted. However, they disappeared from the market due to financing problems. Currently we can say that only institutional magazines, such as Kaikan of the Peruvian Japanese Association and AELU of the Estadio La Unión Association, are the most representative.

UNFORGETTABLE RADIO PERIODS

Japanese journalism also ventured into radio. Don Augusto Shozen Irei Shimabukuro is the representative figure in the radio world. It acquired Radio Inca in 1954 (previously known as Radio Restauración), from where it could comfortably transmit various programs for the community. But the greatest merit that many remember is his radio program: La Hora Radio Japonesa , or simply La Hora Japonesa .

It was a program that was not only spread in Peru, but was replicated in different Latin American countries. In a time still tense due to the war, the radio was the best instrument to continue transmitting information and culture to the community, at that time reserved and with a low profile. For this reason, many compare La Hora Japonesa with Perú Shimpo due to the important journalistic work it had.

The history of La Hora Japonesa begins in February 1952. At that time it was known as Musical Gloses and Amenities of Japan , a name that was a bit long but that summarized the content of its programming. Over time it was renamed: The Japanese Hour .

The programming was varied and in Japanese (although it also included Spanish). There was Japanese music, especially of the enka genre, to liven up the day. From a Japanese station (Taiyo no Hohemi) they took the short self-help stories they broadcast (which many of us were lucky enough to read in the book Sonrisas del Sol and in Perú Shimpo a few decades ago).

Like any program on the air, sponsors could not be missing. Due to the success of the program, many businesses, large and small, were present, including Inka Kola, all related to the community.

Its popularity was such that it was broadcast on Radio Inca almost every day (except Sundays) and at three times (morning, afternoon and night). And there was not only one, but several Japanese hours both in Lima and in the provinces.

The difference with Japanese Latin American hours was the death notes. According to Japanese researcher Tetsuya Hirahara, Shozen Irei's Peruvian Japanese Hour was the only one that included them in its programming.

La Hora Japonesa managed to stay on the air for 36 consecutive years on the same radio station, although in its beginnings it passed through other stations (Radio Lima and Radio Atalaya).

In addition to La Hora Japonesa , there was another radio program that was also broadcast on Radio Inca, but whose programming was more focused on the music of the moment and the Nisei youth of that time. The name of the show says it all: Japan A Go Go . It was hosted by Jaime del Águila, the same one who ran Cinco Continentes , a television program where many of its chapters were dedicated to Japan and Okinawa, another example of journalism in the community, of a cultural and tourist type.

Note:

1. World War II

Sources:MATSUDA, Samuel. Walking for 75 years on the roads of Peru . SAKUDA, Alejandro. The Japanese press in Peru (published in Discover Nikkei). DEL ÁGUILA VILLACORTA, Jaime. Five continents (website). FUKUMOTO, Mary. Towards a new sun . Peru Shimpo

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 100, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2015 Texto: Asociación Peruano Japonesa / © 2015 Fotos: Museo de la Inmigración Japonesa al Perú “Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka”