What kind of Nikkei are the "next generation of Nikkei1 "? Are they simply the descendants of Japanese who emigrated to Latin America - third, fourth, fifth generation, etc. (including not only Japanese, but also people of other races and ethnicities such as half and quota2 )? Or are they the "millennials" generation of Nikkei who have moved away from Japaneseness, young people who are free of ties, have a weak sense of belonging, are flexible, like new things, and are interested in Cool Japan elements? Or maybe they are a generation that has a little of all of these elements. I would like to examine what the "next generation of Nikkei" are interested in these days and how they are doing it, what they expect from Japan, and how Japan can make better use of such human resources.

There are 3 million Japanese descendants in the world, with 1 million in the United States, 1.65 million in Central and South America (estimated 1.5 million in Brazil, 90,000 in Peru, and 30,000 in Argentina), and about 240,000 in Japan (180,000 Buzilar, 45,000 Peruvian, etc.). It has only been about 60 years since Japanese people immigrated to agricultural settlements in Paraguay and Bolivia and the Dominican Republic, but many Japanese communities in other regions have a history of over 100 years. As the generational change progresses, the number of families with non-Japanese descendants is increasing, and their feelings and expectations toward Japan are quite different from those of immigrants.

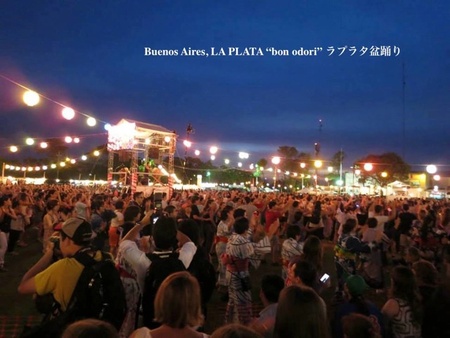

The current change is also reflected in the fact that existing Japanese associations are no longer representative organizations of the Japanese community. Active Japanese groups are run by young and middle-aged second generation members, who set goals for each project and carry out activities that are commensurate with their funds. There are many voluntary organizations such as circles without legal status, and groups that specialize in project planning such as Bon Odori and Japanese festivals. When local governments plan immigrant festivals and cultural events, these groups actively participate. Groups and circles that do not collect annual fees (and in fact cannot) secure their own financial resources through trial and error with little funds, and operate in a style that does not increase fixed costs. They avoid physical projects and positions in organizations that have become a formality, and flexibly change their goals and projects depending on the economic situation and financial situation at the time. Even if there are organizations that cooperate with them, the younger generation of Japanese people do not have a strong sense of belonging to any organization.

A key characteristic of the next generation of Nikkei is that they are open to cooperation and participation from non-Nikkei people, and they work together to a degree incomparable to before. The larger the event, the more essential the participation and cooperation of non-Nikkei local residents becomes, but many of the organizations that have been able to secure cooperation from non-Nikkei have succeeded in increasing their own financial resources. For example, the Japan Festival (Festival do Japao) , held annually in São Paulo, Brazil, is planned and implemented by the Union of Japanese Prefectures in Brazil. Many of the organizing committee members are second- or third-generation Nikkei, and more than half of the visitors are non-Nikkei. Chairman Yamada states, "The Japan Festival has gone from being an event for Nikkei people to an event for São Paulo itself." 3

Thus, instead of setting up Japanese language schools and Japanese associations (assemblies, etc.) for Japanese people, we need to plan Japanese language classes and events for the general public who are interested in Japan, and ensure that not only Japanese and Japanese people, but also local non-Japanese people can participate comfortably and enjoyably. Bon Odori festivals and bazaars are good examples of this. It will also no doubt become more common in the future for non-Japanese instructors to teach Japanese4 .

Many of the next generation of Nikkei people cherish their grandparents and great-grandparents, the "Issei" Japanese immigrants, but they don't know much about the path they took over the last 100 years or the situation Japan was in during that time. In the Nikkei community, there is sometimes a biased understanding that emphasizes the stories of hardship from a victim mentality, but recently, books and manga have been published in Spanish and Portuguese that introduce the history of Japanese immigration in an easy-to-understand and visual way (for example, the manga book "Los SAMURAIS de México, Hisashi" UENO, published by the Nikkei community in Mexico), making it easy for even the younger generation to learn about Nikkei history.

Furthermore, historical museums on the theme of Japanese migration have been established in Brazil, Peru, and other countries. In particular, the museum run by the Peruvian Association of Japanese Peruvians (APJ) in Lima introduces the history of Japanese migration in an exhibition format that is easy to understand even for the younger generation5. In the future, it will be necessary to make the facility more accessible to non-Japanese people as well, and to have influential Japanese people who are good at speaking visit local schools and universities to give lectures and hold visiting classes. Even if it is only by using manga, simply seeing how events and international situations have influenced each society at the time will surely increase understanding and trust in the Japanese community.

Japanese descendants are active in various fields and are an important soft power for Japan, but a more mid- to long-term vision is needed to build a practical cooperative system. Japan is trying to be more proactive in business relations and cultural exchange with South America, and there are high expectations of Japanese descendants. However, in order to do so, both parties need to be prepared and agree to take risks together and gain benefits. Japanese descendants have sometimes experienced painful persecution and unreasonable discrimination due to misunderstandings and prejudices in their own society, but they have valued their differences and won respect based on unimaginable efforts and sacrifices. This is why Japanese descendants can become a powerful overseas partner that can manage the diversity and unexpected friction and confusion that Japan needs today.

Future policies for Japanese communities in Latin America and the Caribbean must aim for various partnerships and cooperative relationships with Japan, based on the past achievements of Japanese people and their future potential. It is necessary to create methods and mechanisms for utilizing Japanese people more strategically, not simply as recipients of support, but as direct and indirect partners of Japan.

We must have the idea of spreading cultural phenomena such as Japanese language education, the dissemination and popularization of Japanese culture, and Cool Japan, which is popular overseas, overseas more than ever before through Japanese people. However, this does not mean that everything should be done through Japanese people. There are many wonderful people among non-Japanese people as well. For example, there are people who became pro-Japan and knowledgeable about Japan after studying in Japan, and who continue to use what they learned in Japan to teach Japanese in their home countries or third countries, run not only anime and manga classes but also full-scale calligraphy classes, and engage in activities that rival those of Japanese people. Successful Japanese organizations and circles are also supported by such non-Japanese talent.

It would be desirable for Japan to make more practical use of these human resources by mixing them with Japanese descendants as a policy in the future. Training in Japan and Latin America may also be a good idea for both Japanese descendants and non-Japanese descendants, depending on their field of expertise and occupation. For Japanese descendants, this would be a good stimulus and challenge. For Japan, it would mean securing many more allies and strengthening its soft power.

Notes:

1. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been implementing the "Next Generation Japanese Leaders in Latin America" program, inviting prominent Japanese leaders to hold discussion meetings and informal meetings with Japanese officials for several years. The aim is to promote mutual understanding, international exchange, and the expansion of Japan's overseas network. Meanwhile, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), at the initiative of the Japanese government (a proposal that arose during Prime Minister Abe's visit to South America), has been inviting 20 Japanese university students since last year in addition to training programs in various industries, to meet many people and organizations during their approximately one-month stay, visit tourist attractions, and increase their interest in Japan.

Alberto Matsumoto, " The Role and Expectations of the Next Generation of Nikkei Leaders ," Discover Nikkei, June 2015

2. In recent years, the terms "double" and "mixed" have been used to mean "half-quarter" in the sense of someone with two (or more) cultures or ethnicities. In this article, we use the term "half-quarter" for convenience, but we do not intend it to have a negative connotation.

3. " Prefectural Federation Meeting: Preparations begin for next year's Japan Festival: Young people should participate in the 50th anniversary ceremony " (Nikkei Shimbun, August 3, 2016)

4. Many Japanese and Japanese-Americans become Japanese-language teachers after receiving teacher training with support from JICA or the Japan Foundation. In contrast, many non-Japanese teachers learned Japanese to translate manga and anime, learn Japanese drums and Soran Bushi, cook, and learn art. Many of them study in Japan at their own expense and have mastered the language and culture to a certain extent.

5. The La Paz Japanese Association in Bolivia has a compact but very easy-to-understand museum that introduces the history of the community. The most important thing is that it is easy to understand and that it is interesting and attracts the interest of not only Japanese people but also students and the general public in the local community.

The APJ Lima website (mainly in Spanish) contains information about the history of Japanese immigration, as well as information about monuments and places related to Japanese people in the country, and how to obtain documents. The museum is named after a prominent Japanese person, Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka, and the naming fee is used to cover the museum's operating costs.

© 2016 Alberto J. Matsumoto