Read part 1 >>

Schooling in Chicago

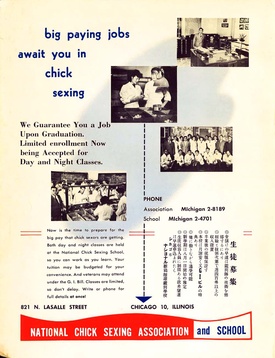

At the end of World War II, many Japanese Americans resettled in places like Chicago, as they tried to rebuild their lives after roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans had been incarcerated in Japanese American Concentration Camps during the war. And for some young men and women, returning from the camps or active military service, an eagerness to rebuild their lives brought them to the lucrative trade of “chick sexing,” an occupation that was emblazoned in full page ads in Japanese American magazines and guidebooks, and which could be paid for with G.I. Bill funds.

With a primarily Nisei student base paying around $300 for tuition and the cost of chicks for their final examinations, many Japanese Americans found in chick sexing a livelihood which supported not only themselves, but also their families.

Roy Akune attended the National Chick Sexing Association in 1953 after being told about it by Mark Sugano. According to him it would take about three years to be a good chick sexer, including time spent being under an apprenticeship, before being able to work on one’s own. During the day Roy worked at a dry cleaner called Sun Cleaners, and attended chick sexing classes at night.

(Collection of the Japanese American Service Committee in Chicago)

“In those days chick sexers used to make good money. When I used to work, everyone used to make at least $1 to $1.50 an hour, and if you were an expert chick sexer you made $10-$11 an hour,” noted Roy.

At the beginning Roy would make as much as $6-$7 an hour. The chick sexing associations would take a commission of 15% upon starting in the profession, and would later reduce it to 10%, to cover the costs of finding contracts for new workers. Seasoned veterans could amass earnings as high as $3,000 for a season of work, which was quite a sum by 1950s standards.

“It was one of the top wages in those days. Even a carpenter used to make maybe $2.50 an hour,” Roy continued. “But if you were good at it, you’d have to do it guaranteed, at better than 98% correct. Usually you need to be at least 97% correct but if you go under that, you have to pay a penalty. If you make too many mistakes, whatever mistakes you make you have to pay back to the hatcheries.”

Often requiring some three to four months of night classes to get their speed and accuracy up to the right level, practically no non-Japanese learned this skill.

As Roy related, “Maybe the hakujin (Caucasians) didn’t have any patience. Maybe the Japanese had more patience. You had to have a lot of patience. Sometimes you’d have 10,000 chicks behind you, so you had to go through 1,100 to 1,200 an hour. You had to go pretty fast.”

“The fastest I ever did was 1,400 to 1,500 an hour. Certain chickens were easier than others. Some breeds were harder. Cornish hens were very easy to kill You had to squeeze its stomach, to take their poop out, before checking their sex organs. Some breeds were weak and passed out.”

Though only a few Japanese American women practiced chick sexing, Patti Sugano’s mother, and also her aunt Ayako worked as chick sexers. Her mother worked in this profession through the mid-1960s, which is around the time that the chick sexing school in Chicago closed.

Patti remembered the sorting process that her mother would be involved in, stating that “I remember my mother throwing a chick to one side or throwing the chick to the other side into a cardboard box which was for the girls, while males would sometimes go into a big steel drum, where they would suffocate.”

“I also remember her bringing chicks home and she would have to drive them over to Lester Fisher (a Lincoln Park Zoo veterinarian), because the snakes ate live chicks. That’s just kind of the way it went.”

A Life on the Road

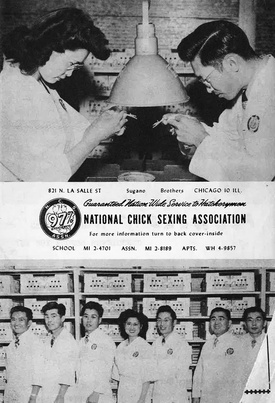

(Collection of the Japanese American Service Committee in Chicago)

Following their training, Japanese American chick sexers would then have to contend with many grueling hours on the road and much time spent away from home.

“Of the dozen or so who started, only about three kept sexing,” Jimmy Doi noted. “Most of the others quit after the first year.”

As Johnny Asamoto, Jimmy Doi’s brother-in-law and a fellow chick sexer stated, “During this time the industry consisted of many small hatcheries which all had to be serviced. Therefore the travel involved was great and we bought a new car every two years. Because the season was from January to June, it invariably involved some difficult drives in the snow to get to the next hatchery where the next batch of chicks was due.”

“So they would get a phone call saying when they were going to be hatched, because it could be all hours of the day, and they would always wear regular clothes with a white uniform,” noted Patti Sugano.

“My mother would be driving in the middle of the night in Indiana, and she would stay in somebody’s home or a hotel, and the hatcheries really liked my mother, because she was a really hard worker.”

But I remember she’d say to me that she’d have to get to a hatchery really fast so she’d be driving about 80 miles an hour down a lane and all the policemen knew her, and they would say ‘Don’t stop that car because she’s getting to the hatchery to do the chick sexing.’ It was a different time, you know.”

Despite the demand for the skills of the chick sexers, post-World War II discrimination against Japanese Americans continued to linger, with many chick sexers having to endure racism, both subtle and blatant.

As Patti Sugano related, “I do remember my mother telling me that one time she was going through a toll booth and there was a person in the toll booth, who asked my mother what nationality she was. And when she said ‘Japanese,’ they refused to let her go through the toll booth, and told her to find another way.”

“So she said the next time she went through a toll booth and somebody asked her what nationality she was, she said she was ‘Chinese,’ and they said ‘Oh, okay,’ and they let her through. She said to me ‘Oh, I didn’t have time to go find another route.’ So I think she may have experienced some discrimination, but my thought now is that they needed her more than she needed them. Without the chick sexers there would have been a problem.”

“It wasn’t like they were moving in taking over jobs or anything like that. They were doing something that these hatcheries needed, so that may or may not have helped.”

Despite the ethnic nature of the chick sexing industry, the long hours in distant states equated to labor practices that were difficult and arduous. Scholar Azuma Eiichiro noted that this could sometimes lead to labor unrest and union organizing, writing that “As ‘the result of many separate requests,’ a Chicago group was first granted ‘a much coveted charter’ from the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America (AMCBW) in September 1958. Led by Eddie Fukiage, the union pushed beyond the Midwestern States, asking their fellow Nisei sexers to organize local chapters in California, the Rocky Mountain region, New York, and Georgia.”

Support for the unionization efforts was not always forthcoming, particularly with the association owners, and though many did join the union, such efforts eventually came to naught. As noted by John Nitta, operator of Amchick, “The meat cutters union in Chicago tried to unionize Amchick and failed.” According to Eiko Koto, whose husband operated an association in Georgia, “the question for the government and the IRS was whether the sexers were independent contractors or employees.”

A Seasonal Trade Leading to Other Occupations

(Collection of the Japanese American Service Committee in Chicago)

For those who stayed in the industry, travel to faraway places like Nebraska or Iowa for the chick sexing season would be offset by quiet time at home in Chicago or the pursuit of other occupations. Michael Doi, a chick sexer who had also trained in Chicago, continued to work at his regular job at the Paymaster Corporation, a company which developed and sold check writing machines. Johnny Asamoto worked in the produce industry outside of the chick-sexing season, and the dual incomes he earned helped to support the raising of his son and daughter.

As Bob Hontani, another chick sexer who had attended school in Chicago noted, “This seasonal work left much time for other business, so after the 1953 season was over, another sexer Jim Sakamoto, and I bought a bar in Chicago which we named Club Jimbob, combining our names. We started with a two piece Hawaiian guitar band and later changed to a piano player. I bought out Jim in 1955 and kept it until the end of 1958. Two caretakers tended the bar while we were gone sexing chicks.”

Roy Akune continued to work for the McClurg wholesale company outside of the chick sexing season. For him, the decision to quit the profession came as he got older and it got harder to see. Eventually he was able to use his savings to purchase a dry cleaner in Chicago, which then became his main profession.

Over time, the gradual consolidation of the hatchery industry in the U.S. contributed to the decline of the small hatcheries that had most needed Japanese American chick sexing laborers. This factor, along with the development of new techniques for sexing chicks, helped contribute to the slow decline of Japanese American involvement in the industry.

Though growing professionalization in the Japanese American community has meant that few today remember this remarkable occupation, the legacy of chick sexing continues to resonate for those families that were able to advance, in part, due to the particularity of this unique, underappreciated, and oft-forgotten, Japanese American ethnic enterprise.

Sources:

Many thanks go to Patti Sugano and Roy Akune for agreeing to be interviewed in the development of this story. Additional thanks go to Andrea Sugano for helping me to contact these two interviewees.

Interview quotes from Johnny Asamoto, Jimmy Doi, Michael Doi, Bob Hontani, and Eiko Koto are excerpted from interviews from the now defunct website www.poultrysorters.org that was run by Joyce Hirohata and the late Dr. Tommy Nakayama. Many thanks go out to Joyce Hirohata for granting me permission to use excerpts from the website interviews in developing this article.

Adams, A.D. “A Nisei Makes Chick Sexing an International Profession.” Far East Photo Review, 1948. Content originally posted in the now-defunct www.poultrysorters.org website.

Azuma, Eiichiro. “Race, Citizenship, and the ‘Science of Chick Sexing’: The Politics of Racial Identity Among Japanese Americans.” Pacific Historical Review 78, no. 2 (2009): 242-275.

Lunn, John. “Chick Sexing.” Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society 36, no. 2 (1948): 280-287.

Nitta, John. “Interview.” Terminal Island Life History Project. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2001.

© 2016 Ryan Masaaki Yokota