The spring of 1935 was a time of slow financial recovery and international unrest. Adolph Hitler had seized power in Germany in 1933. Japan and Germany left the League of Nations. Dachau, the first of a thousand concentration camps was established. What eventually would be 1,400 German laws aimed at non-Aryans and Jews were in motion. In April 1934, thousands of Americans attended a pro Nazi rally in Queens, New York. By July 1934, 30,000 were imprisoned in Germany.

The unease that spreads in times of financial uncertainty (the Great Depression), environmental devastation (the Dust Bowl), and world conflict (departures from the League of Nations) has a way of creeping into local politics and immigration policies. Sentiment against immigrants from Asia had been in California since the mid 1800s, beginning with the Chinese. By 1935 in California, there had been two and a half decades of legislation aimed at restricting immigration from Japan, restricting property ownership and restricting citizenship.

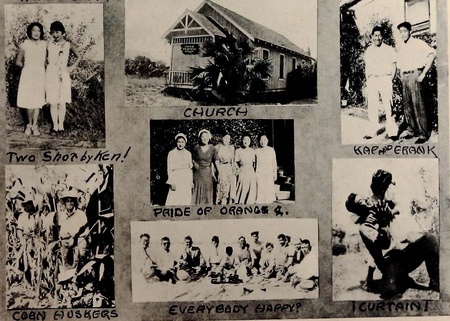

At the time of the banquet in spring 1935, the Wintersburg Mission (founded in 1904) had already opened its second and larger 1934 Church building, funding its construction during the Great Depression. Huntington Beach was opening a new post office on Main Street, funded by the federal program that became the Works Progress Administration. New arrivals escaping the mid-western Dust Bowl were showing up in California looking for work. It was the New Deal era. People were toughing out hard financial times, but still were hopeful for the future.

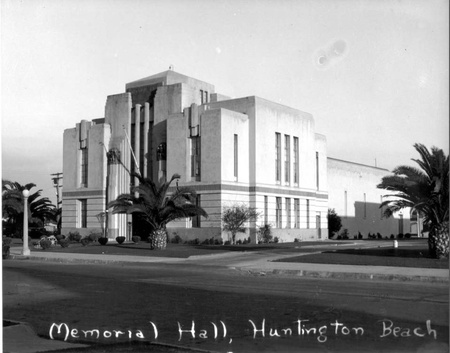

In Wintersburg Village and Huntington Beach, the local farmers and merchants were determined to keep things moving in a positive direction. On April 22, a banquet was held in the Memorial Hall with community leaders specifically “in honor of the Japanese citizens of this community.”

The Santa Ana Register reported the next day that 200 prominent citizens attended and that “the talks while brief were expressions of the friendly relations that exist between the business men of the community and the Japanese residents, and was planned as a tribute to the Japanese.”

The Los Angeles Times described the dinner’s symbolism, “cherry blossoms and California poppies were twined into a banquet of peace and good will here tonight.” Japanese Consul General Tomokazu Hori was the special guest and keynote speaker for a special dinner in Huntington Beach to celebrate and strengthen relationships, assisted by the new generation of Japanese Americans: the Nisei.

The dinner’s chairman and toastmaster, Ralph C. Turner—owner of M.A. Turner Co., a dry goods and sundries store on Main Street in Huntington Beach—quoted Los Angeles Times journalist and columnist Harry Carr, who had said that a “Golden Age always follows upon the blending of the East and the West.” Consul General Hori agreed and “gently” spoke of the propagandists working to divide the countries.

Huntington Beach Mayor Thomas Talbertwelcomed everyone, along with members of the Huntington Beach city council, the Huntington Beach Chamber of Commerce, Windsor Club, Rotary Club, the Business Men’s Association, the Smeltzer Japanese Association, the Orange County Japanese Association, and the Japanese American Citizens League, among others. Anyone who was anyone, was there.

The Japanese American pioneers of Wintersburg Village and Smeltzer had worked for three and a half decades to create a life in America. The banquet recognized these efforts and brought together farmers and merchants from the surrounding countryside. They knew each other and wanted to hold back the rumblings of international and domestic conflicts.

From the beginning, Orange County’s Japanese pioneers worked to build community relationships, providing popular “daylight fireworks” and night time fireworks for Huntington Beach’s first Independence Day celebrations. They helped raise funds to rebuild the Huntington Beach pier in time for its re-dedication in 1914, at which the Japanese American community participated in the celebrations. The Japanese pioneer community in Wintersburg Village had rallied in WWI, raising funds to support the American Red Cross.

The annual celebrations of the Emperor of Japan’s birthday also had served as popular cultural events to which the surrounding community was invited for music, food and performances (and local residents came by the hundreds). Masami Sasaki, the owner of Chili Pepper Dehydrating, Inc. (known as the “Chili Pepper King”), had provided a youth community center where students learned judo.

As the American-born Nisei came of age, the Japanese American community had come to the moment faced by every immigrant community when old country traditions meet new country modernity. The Los Angeles Times mentions more than once that the young Nisei ladies in traditional kimonos of gold, red, and purple “were bright spots” at the banquet, while also noting that Leonard Miyawaki “pleaded for an understanding of the problems of the second-generation Japanese and urged defeat of anti-Japanese legislation in the Legislature.” Miyawaki’s parents had run the Japanese market known as the “Rock Bottom” on Main Street in Huntington Beach (217 Main Street, today’s Longboard Restaurant & Pub).

Consul General Hori was probably relieved by the warm welcome in Huntington Beach. He had been dealing with extreme unrest in Arizona’s Salt River Valley. Japanese American and Hindu farmers were being harassed and attacked, sometimes by masked men. Militant Caucasian farmers formed anti-Japanese groups and were encouraging bombings, shootings, arson. These groups had begun calling for the removal of all people of Japanese descent from Arizona. The arrival in March 1935 of the U.S. Department of Justice and a threat from Washington D.C. that Arizona would not get its New Deal funding brought the conflict to a halt.

The mid-April 1935 banquet in Huntington Beach was held only days after things had begun to settle in Arizona. A week earlier, the Consul’s wife, Taeko Hori, was a guest at the Women’s University Club supporting speakers with a message of maintaining friendship between Japan and America. Speaker Ken Nakazawa, an art professor at the University of Southern California, told the group that “patriots who try to show their devotion to America by manifesting hatred of other nations are a menace to the peace of the world.” He implored American women to join hands with others across the sea in the interest of friendship. The Consulate staff was at every conceivable community event, working to solidifyrelationships.

To further the cultural ambience of the gathering, Mary Chino of Chula Vista—the daughter of Tsuneji Chino, a celery farmer and prominent Southern California community leader who had lived in Wintersburg Village—sang “flute-like” arias from Madame Butterfly and other operas. Garden Grove’s Alice Setsuka Imamoto—a nationally-recognized pianist at age 8—provided more classical music. Short speeches by prominent citizens and elected officials were welcoming and encouraging for the future.

The Los Angeles Times described the Huntington Beach banquet as “more than an amicable gathering...Japanese have settled here as farmers. They have raised gold fish. They have cultivated flowers. They have raised birds.” The sentiment of the media covering the event was flattering and positive.

On this night in Huntington Beach, in a time of unsettling rhetoric, the leaders of the community made a public statement about keeping friendships intact and they had invited the media to witness it.

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on August 8, 2016.

© 2016 Mary Adams Urashima