A few weeks ago, I awoke in the middle of the night and heard President Obama’s familiar voice. I hadn’t planned on listening in real time to his speech in Hiroshima, but his usual eloquence lured me to stay up and watch.

“Seventy-one years ago, on a bright cloudless morning, death fell from the sky and the world changed,” Obama had begun his solemn address. “Why do we come to this place, to Hiroshima? … We come to mourn the dead… Their souls speak to us.”

“The world was forever changed here, but today the children of this city will go through their day in peace… That is a future we can choose, a future in which Hiroshima and Nagasaki are known not as the dawn of atomic warfare but as the start of our own moral awakening,” he concluded.

Obama then embraced and shook hands with hibakusha as Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe looked on awkwardly. Later, he left behind origami cranes purportedly made by him at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. President Obama left no doubt of his gift for stirring oratory and magnanimous gestures.

In the next few days, I read varied accounts of Obama’s visit in news reports and on social media. Many survivors of the atom bombs and Japanese who grew up in post-war Japan were genuinely moved. And on both sides of the ocean, it seemed that many people were captivated and wanted to believe that peace and a nuclear-free future was possible. Taking the speech at face value, I was among them, but also realized from decades of work in peace movements that such noble goals are not easily reached.

The Long Road to Winning Peace

As a child growing up in Japan in war’s aftermath, I can recall grownups around me talking about the hardships of war and the horror of the atomic bomb. My own pilgrimage as a grade-schooler to see the ruins of the Genbaku Domu (Atomic Dome) left an indelible impression on me.

After coming to America and attending public schools, I went to UCLA in the 1960s where I got involved the civil rights and Black Power movements, the demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, and efforts to build an Asian American movement.

I learned that the Vietnam War was not only an act of U.S. aggression, but there was a dimension of racism connected to it with the disproportionate numbers of black and Latino GIs becoming fodder in a war to decimate a small Asian country. The recently deceased Muhammad Ali, who had refused to be inducted into the armed forces, was quoted as saying to defenders of America’s status quo:

“… I could be [in jail] for four or five [years], but I ain’t going no 10,000 miles to help murder and kill other poor people. If I want to die, I’ll die right here, right now, fightin’ you, if I want to die. You my enemy, not no Chinese, no Vietcong, no Japanese. You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice. You my opposer when I want equality. Want me to go somewhere and fight for you? You won’t even stand up for me right here in America, for my rights and my religious beliefs. You won’t even stand up for my rights here at home.”

In the mostly white mainstream anti-war movement, many people of color felt a need to voice our distinct views that were shaped by our experiences of being a minority in this country. I helped to organize Asian Americans for Peace in 1969 to march through the streets of Little Tokyo to demonstrate our opposition to the war. And we followed up with teach-ins, rallies, study groups, and other activities.

In 1971, I was chosen to attend a world conference against A- and H-bombs in Tokyo, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Okinawa. During that trip, I met many peace and anti-nuclear activists as well as hibakusha, zainichi Koreans, and burakumin. Millions of Japanese people took part each August in the commemorations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

And activists were involved in year-round campaigns to oppose the U.S. Japan Mutual Security Pact (AMPO Funsai!) because they viewed the treaty as inconsistent with Japan’s Peace Constitution. (Not long ago, I learned that Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, who pushed for Japan to be under America’s “nuclear umbrella” rather than to be a truly neutral, pacifist nation, is the grandfather of the current prime minister, Abe. More on this later.)

By the 1980s, the “two superpowers”—the U.S. and Soviet Union—were engaged in an all-out nuclear arms race as the Cold War heated up under President Reagan. He was a virulent anti-communist and a war hawk. He promoted nuclear weapons and delivery systems such as the B-1 bomber, the neutron bomb, the Trident nuclear submarine, and the MX missile.

Again, there was a resurgence of the peace and anti-nuclear movement around the globe. In the U.S., mainstream groups like Physicians for Social Responsibility, Women Strike for Peace, and SANE/Freeze organized large demonstrations. Because we believed that the voices of Hiroshima survivors, particularly those of 600 or so hibakusha living in the U.S., should be heard, we formed a group called Asian American for Nuclear Disarmament (AAND). We also tried to highlight the threat of new nuclear weapons being stockpiled in Asia. Our slogan was “No more Hiroshima! No more Nagasaki! No more Vietnam!”

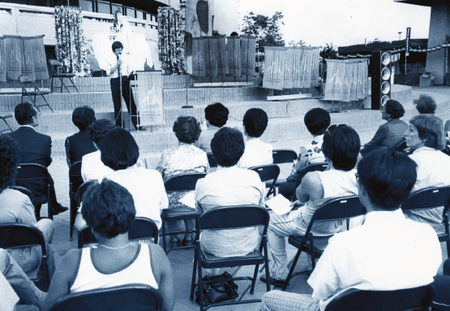

In Little Tokyo, we sponsored premiere film screenings of Barefoot Gen (Hadashi no Gen), a film based on a Japanese manga series by Hiroshima survivor Keiji Nakazawa, at Higashi Honganji. We worked with local hibakusha to commemorate August 6 and 9 in the JACCC Plaza and other venues, and we got together with students to organize teach-ins on campuses.

By the beginning of the 2000s, it seemed that nuclear destruction many times greater than Hiroshima was becoming more plausible as countries with nuclear capabilities had multiplied. China, France, and the U.K. joined the U.S. and Russia as “nuclear-weapon states.” India, Pakistan, and North Korea had conducted nuclear tests, and Israel was widely believed to have nuclear weapons. Both Iran and Iraq were suspected of trying to build an arsenal of chemical, biological, and possibly nuclear weaponry to be deployed in regional wars.

After President Bush invaded Iraq in 2003 under the pretext of seizing “weapons of mass destruction,” we began working with Veterans for Peace, Veterans Against the War in Iraq, Asian American Vietnam Veterans Organization, and many others to protest escalation of violence in the Middle East.

Obama’s Soaring Rhetoric and the Intractable Reality of U.S. Foreign Policy

As I listened to Obama, even as I thought about this long history since 1945, I wanted to believe that world leaders are working to “ultimately eliminate the existence of nuclear weapons.” But I know that his soaring disarmament rhetoric does not conform to the reality of global powers continuing to stockpile nuclear weapons.

According to The New York Times, “a new Pentagon census of the American nuclear arsenal shows Obama’s administration has reduced the stockpiles less than any other post-Cold War presidency.” Comparing the eight years of George W. Bush’s Pentagon budgets and the eight years of Obama’s, Obama’s exceed the hawkish Bush’s by $816.7 billion ($4.12 trillion for Obama’s two terms, $3.3 trillion for Bush’s).

And as the presidential election unfolds in the coming months, I cannot imagine the dangerous, unstable, and unpredictable future that a Donald Trump victory would create. But even under a Hillary Clinton administration, the threat of international tensions leading to the use of nuclear weapons cannot be dismissed.

At the same time, the ruling coalition headed by Prime Minister Abe successfully passed laws to reinterpret Japan’s Peace Constitution to allow the Self-Defense Force to be deployed overseas. This happened despite a vigorous and protracted opposition by student activists led by SEALDs and other peace seekers. Next month, Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party will face stiff challenges from anti-war forces in the election of Japan’s legislators.

* * * * *

In earlier times, I took part in numerous activities and movements to advance the cause of world peace, but in the recent past, I feel I have not done enough to earn the label of “peace activist.” I want to be a part of a large, effective movement to counteract aggression and war. I hope WE, as a people, can help to rebuild the peace movement in concert with the environmental movement and the struggles for political and economic power for the people of this country and social justice for everyone in the world.

* This article was originally published on The Rafu Shimpo on July 13, 2016.

© 2016 Mike Murase / The Rafu Shimpo