The ocean has always had great significance in the life of Mitsuya Higa. Ever since he was a child, he has been going to Callao’s La Punta district to swim or simply gaze at the sea. Now 83 years old, he no longer swims, but he still visits La Punta regularly because, he says, the ocean fills him with peace.

While living in Madrid in the 1960s, chasing his dream of becoming a matador, he missed the ocean. “I needed my bit of ocean, to see a lot of water in one place,” he says.

When I visit, I always ask him: “Uncle, do you want to go to La Punta?” “Let’s go,” he answers. We almost always talk about the past. About his memories, especially those of his childhood in Callao and his life in Spain.

His childhood is inextricably linked with World War II, which began when he was seven years old. The Japanese and their descendants were the target of violence and it didn’t matter that he was only a child. Mitsuya was always on his guard while walking through the streets, using his instinct to avoid potential assailants.

“Like a stray dog, I always walked close to the wall (looking all around with fear and mistrust), because I could be walking along and thump! I’d feel a blow, a kick, someone hitting you, or they pulled your hair; even women who I didn’t even know. That’s why I always say that I had to walk on my guard like a stray dog, looking to see where you can go.”

Nor could he find safety in the darkness of movie theaters, where once a group of boys sitting two or three rows back urinated on him.

Movies had a strong influence on his childhood and adolescence. Hollywood war films, where the Japanese were portrayed as the villains. Movies that made him hate the Japanese.

“I always say, look at what alienation can do. Even I watched the movies and said, ‘Damn Japanese.’ I didn’t want to be Japanese.”

Despite all of the attacks he endured, he harbors no bitterness. He says he understands that many people’s behavior was influenced by the climate of the time, an anti-Japanese campaign in the press, and the Hollywood machine. Mitsuya says that if the films made a Nikkei like him feel hatred toward the Japanese, then clearly they would have an even stronger effect on those who are not of Japanese descent.

SPAIN, FULFILLING A DREAM

Mitsuya was a boy when he discovered his life’s passion: bullfighting. Among the customers of his father’s dairy was a group of dockworkers who were also amateur bullfighters. Mitsuya listened to these men talk about bullfighting and although he didn’t understand anything, the excitement in their words pulled him in.

The workers traded foreign bullfighting magazines, leaving them with Mitsuya to keep. For him, the publications were like superhero comics for other children and he immersed himself in them like an ocean with hidden treasure in its depths. A future bullfighter was born.

If his journey by boat to Spain in 1962 was the most important trip of his life, the second most important one was the horseback ride from Callao to the Acho bullfighting ring, where he saw a bullfight for the first time.

The trip was planned by a neighbor, one of his father’s customers who was also a novice bullfighter. Once he learned that little Mitsuya liked bullfighting, he asked if he would like to see it in person. The man had a horse and Mitsuya remembers that one day, they mounted the horse and rode away from his neighborhood at eight in the morning. His parents had no idea where he was going.

Once they arrived in Acho, the novice bullfighter asked an attendant to take care of the “little Chinese boy” while he went to work. He finished the bullfight and they returned home on horseback, another three-hour ride. It was nine o’clock at night when Mitsuya came home. “My parents were waiting for me, and they were very angry. I hadn’t told them anything; if I had, they wouldn’t have let me go.”

Worried about his interest in bullfighting, his mother promptly threw away his bullfighting magazines. Mitsuya fought back.

“When my mother sold the magazines to one of those guys who buys old magazines and newspapers. I didn’t say anything, but I went to a street where they sold old publications and all of my magazines were there. Since I helped out in the dairy, I ‘borrowed’ some money and bought them back. My mother didn’t say anything when she found out, but one night when I returned home there was a bonfire in the street and she was burning all of my magazines. We never said anything to each other about it; we both kept our mouths shut.”

When he told me this story several years ago, I was surprised by the silent battle between Mitsuya and his mother, that way of saying everything without shouting, without reproach, without saying even one word. It astounds me to this day. Is that how Japanese families used to be? Words weren’t necessary because everything was expressed with actions?

Despite his mother’s opposition, Mitsuya didn’t give up. One movie even strengthened his passion for the bulls: Blood and Sand, in which Tyrone Power played a bullfighter. It had another effect: After seeing the film, he decided to become a bullfighter himself.

After finishing high school Mitsuya began studying journalism to please his mother. He even worked as a reporter, but was determined to become a bullfighter so he left journalism to literally launch himself into the bullring. His life as a journalist was on track, but he couldn’t let go of his obsession, so he signed up for a Spanish bullfighting school.

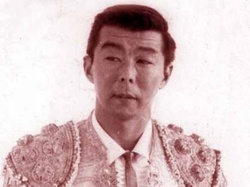

The first time Mitsuya was in the ring it was thanks to a Nisei friend who, with the money from a tanomoshi, organized a bullfight that even featured geishas. The event was really just marketing to promote the first bullfighter of Japanese background in history.

Even though he had become a bullfighter, Mitsuya felt that he hadn’t yet achieved his dream. He felt that he would never be a real bullfighter if he didn’t have a career in Spain, so in 1962 he left everything to move to a country where he didn’t know a soul.

He took several references and letters of recommendation with him, but the only one that worked was the least likely, a letter from a Colombian nun who taught catechism classes to Japanese children. Thanks to her Mitsuya met Manuel Mejías, a former bullfighter known as Papa Negro who was his mentor until his death in 1964.

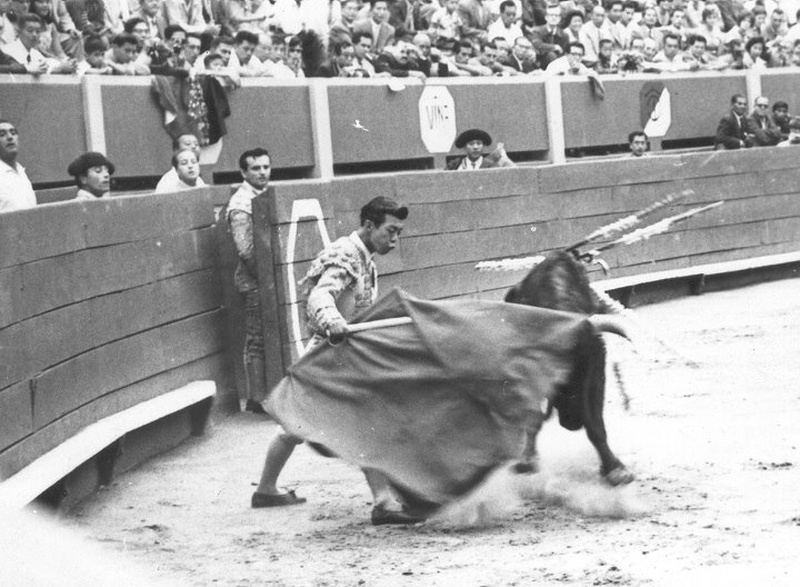

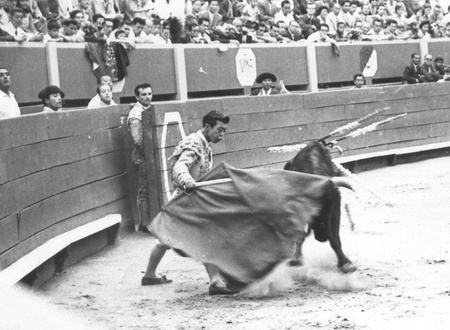

Mitsuya was denied the opportunity to bullfight because no one believed that a “Japanese guy” could be a bullfighter, until Papa Negro’s influence enabled him to debut in Málaga on July 12, 1964. I don’t know if my uncle still remembers how long he had to wait to be in a bullfight, but several years ago he told me that it was exactly “two years, two months, and 21 days after I arrived in Spain.”

It was an historical day. “I had a good debut. I cut an ear and the women threw carnations at me and the men threw cigars, as they did at that time. People came to congratulate me and asked me to sign their fans.”

But another date would become even more important: August 28, 1970. On that day he fought the bulls in Alicante, crowning eight years of struggle and sacrifice. He cut four ears. The other bullfighters with him that day were Palomo Linares and Julián García. My uncle always says that day was more important than even his own birthday.

Before making the decision to be a bullfighter, Mitsuya went to look at the ocean. He needed to see his old childhood friend again, to find some calm before reaching the summit, the dream he’d had almost all of his life. I’ve never asked him, but I imagine that while he gazed at the ocean he thought about The Old Man and the Sea, his favorite novel. He’s often spoken to me about it. He does so with such passion that it seems as if he didn’t merely read it but that he’s lived it, as if he were the fisherman, old Santiago, and not simply a reader. Reading The Old Man and the Sea helps in understanding Mitsuya’s unfathomable character.

I only saw Mitsuya bullfight once. It was in Lima, and he was almost 70 years old. It seemed crazy that someone of his age would face a bull, but leaving a stable life to move to Spain at almost 30 years old, without knowing anyone there, just to become a bullfighter, also seemed like a crazy dream. But that’s how dreams come true.

I don’t remember if I also thought my uncle was a little bit crazy. He was old by then and so determined that he didn’t seem to understand the risk he was taking. Don’t you have to be a little bit crazy anyway to face a bull without fear? I found the answer several years later in an article that Mitsuya had written in 1981 for a magazine called Puente.

Actually, it wasn’t the right question. My uncle told the magazine that as a bullfighter, he was afraid, but that’s not the real issue. This is how he explained it:

“For bullfighters, courage is feeling afraid and knowing how to control that fear, which results in the paradox that a person who has no fear is not brave. And the more fear you have, the braver you are, because there is more fear to overcome.”

MOVIES, HIS SALVATION

My uncle has often spoken to me about his life in Spain. The truth is, since I’m not interested in bullfighting, I don’t always pay attention when he talks about that, but I’m all ears when it comes to his work as an extra in the movies.

Without help from Papa Negro, Mitsuya struggled to make a living. He had a group of Peruvian friends who were studying in Spain, living on what their parents sent them. Since neither he nor his friends had much money, on some days they ate just one meal. This was how he did it: He withstood the hunger until after lunchtime, eating just before dusk so his stomach would be full for the rest of the day. Living in a rooming house, he fell almost a year behind in his rent.

The movies were his salvation. Thanks to his work as an extra, he was able to survive. To be more precise, what saved my uncle were his almond-shaped eyes. At the time, there were few people with Asian features in Spain, so if a film needed extras to play Vietnamese soldiers, for example, he was there.

At the time, many Hollywood movies were being filmed in Spain. Mitsuya made his debut as an extra in 55 Days at Peking, a film directed by Nicholas Ray and starring Charlton Heston and Ava Gardner.

What really interests me about his work as an actor or extra are his anecdotes about movie stars. One of the movies he worked on was Once Upon a Time in the West, directed by Sergio Leone and with a cast that included Henry Fonda, Claudia Cardinale, and Charles Bronson.

What role did he have? He played the part of a Chinese railroad worker. When I saw the film a few years ago, it was strange to think that one of those “Chinese” workers was my uncle.

As for Henry Fonda, my uncle only remembers that he wasn’t around very much, choosing to stay inside his “bunker” instead. He has fond memories of Claudia Cardinale, who was very friendly. He’s told me several times about meeting her, so I know the story by heart, but it’s best to hear it in his own words, which I recorded several years ago:

“Claudia was a great person, very nice, with no pretensions. Almería, where the movie was filmed, is a desert, a barren land where nothing grows. They ‘recreated’ old Western towns there and only the leading actors had trailers or cabins. Since it was very hot and we extras had nowhere to go, we went to Claudia Cardinale’s cabin. She was very gracious, making drinks for us and trying to talk to us; she was a very nice woman, very friendly.”

His anecdote with Charles Bronson is even better:

“He was throwing a ball by himself, with his baseball and glove. Since I knew how to play, I used signals to ask if I could play with him. He went into his trailer to get another glove, gave it to me and we started throwing the ball.”

But there’s another anecdote that tops it: his meeting with Orson Welles at Vistalegre bullfighting arena in Madrid. After being introduced by former bullfighter Pepe Dominguín, Mitsuya said to the legendary filmmaker:

“Maestro, you should make a film about bullfighting.”

“If you write it, I’ll make it,” Welles answered in Spanish with a laugh.

The truth is that at first I thought my uncle was embellishing a bit, but there’s proof: a photo of a young, smiling Mitsuya with Orson Welles’ hand on his shoulder in a gesture of complicity. This photo was later seen by thousands of people in Peru when a newspaper published it as part of a report on the bullfighter.

Mitsuya also played a Vietnamese soldier in the TV series I Spy starring Robert Culp and Bill Cosby, and a Chinese spy in a Spanish comedy.

In one Spanish war movie that Mitsuya never actually saw, he even played a soldier from the United States. It was an amazing experience.

“There were about eight or nine Asians. So that we would appear to be a much larger group, we ran around and around the camera and pretended to be 50 soldiers. We played soldiers from South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and also peasants. We changed our uniforms and became soldiers from another country, and they were killing us everywhere. I’ve never been killed so many times in my life! We even played Americans; of course, they filmed us from far away, in the background, so you couldn’t see our eyes.”

As I’m writing this, I vaguely remember having seen a Peruvian miniseries in the early 1980s called Morenas matadoras (Killer Brunettes), produced to honor the Peruvian women’s volleyball team. All I remember is that my uncle appeared in a pool hall speaking Japanese.

I look up “Ricardo Higa” on IMDb. Nothing. I write “Mitsuya Higa.” That doesn’t work either. Then I remember that the movie in which he played a Chinese spy was called Operación cabaretera (Operation Cabaret Girl) and there I find him under the name “Ricardo Mitsuya.” According to IMDb, Mitsuya was in another Spanish film, ¡Dame un poco de amor…! (Give me a little love), a musical comedy that, according to the synopsis, involved a bizarre story about kidnapped musicians and Chinese men who wanted to control the world. I don’t remember my uncle ever telling me about that movie. The next time we go see the ocean in La Punta I’ll ask him about it. I’ll also ask him if he met Ava Gardner. I suspect he didn’t, because if he had, he would have told me how beautiful she is.

© 2016 Enrique Higa Sakuda