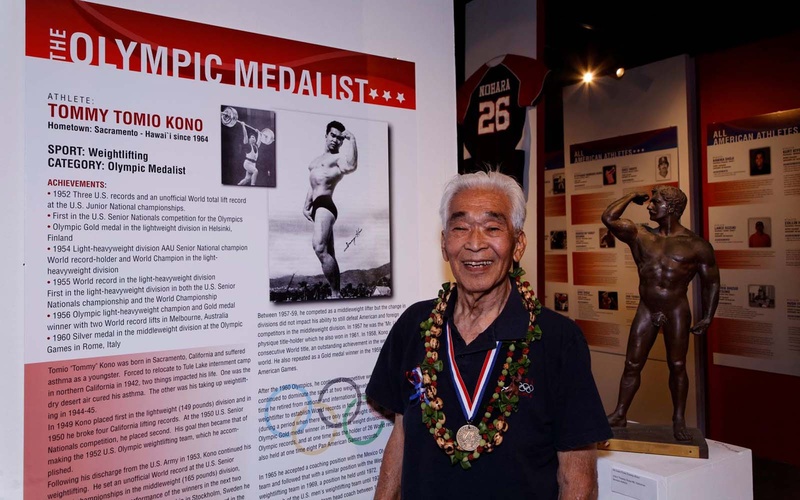

Tommy Tamio Kono, who won three Olympic medals in weightlifting and became head coach of the U.S. Olympic weightlifting team, died on April 24, 2016, in Honolulu, according to The Honolulu Star-Advertiser. He was 85.

According to KHON2, a family member said Kono passed away at 3:30 p.m. Sunday afternoon from complications of liver cirrhosis.

His family said in a statement, “The family would like to thank all of his friends and especially the lifters at the Nuuanu YMCA. He was an inspiration to all who knew him.”

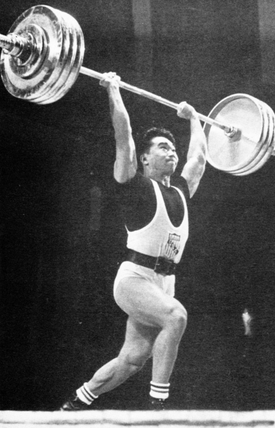

Kono’s Olympic gold medals were in the lightweight division at 149 pounds in 1952 in Helsinki, Finland, and the light-heavyweight division at 182 pounds in 1956 in Melbourne, Australia. He took silver as middleweight at 165 pounds in 1960 in Rome.

In an interview with The Honolulu Advertiser in 2003, former Olympic weightlifter Pete George said of Kono, “He is, in my opinion, the greatest weightlifter of all time. He would always go where the competition was the toughest. Some of us went where we thought we’d get a medal.”

Kono held the titles of World Middleweight Champion (1953, Stockholm; 1957, Teheran; 1958, Stockholm; 1959,Warsaw); World Light-Heavyweight Champion (1954, Vienna; 1955, Munich); Pan-American Games Light-Heavyweight Champion (1955, Mexico City; 1963, Sao Paulo); and Middleweight Champion (1959, Chicago). He took silver in 1962 in Budapest.

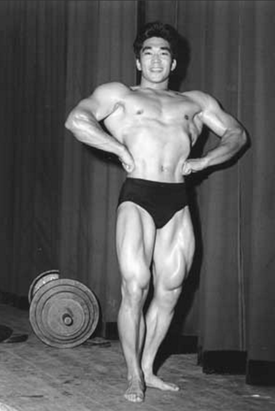

As a bodybuilder, he was named Mr. World in 1954 in Roubaix, France, and Mr. Universe in 1955 in Munich, 1957 in Teheran, and 1961 in Vienna.

He was a hero of bodybuilder, actor, and politician Arnold Schwarzenegger. When Kono and the governor visited the Sacramento High School Weightroom in 2010, Schwarzenegger recalled that as a 20-year-old he watched Kono compete in the World Weightlifting Championships in Vienna and was so inspired by Kono’s strength and physique that he redoubled his own training efforts.

Having established 26 world records, seven Olympic records, and eight Pan-American Games records, he was inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame in Minneapolis in 1990 and the International Weightlifting Hall of Fame in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1994. He received the International Weightlifting Federation’s 25-Year Service Award and Lifter of the Century Award and was one of 100 “Golden Olympians” invited to the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

In 2002, the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California inducted Kono into the Japanese American Sports Hall of Fame along with Ann Kiyomura Hayashi (tennis), Kristi Yamaguchi (figure skating), Wat Misaka (basketball), and Wally Yonamine (football and baseball).

In 2012, Kono was featured in an exhibition, Pride of Hawaii: Japanese American Amateur Athletes at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii.

Born in 1930, Kono grew up in Depression-era Sacramento. When World War II broke out, he and his family were incarcerated at Tule Lake in Northern California. Sickly as a child, he found that the air at Tule Lake helped his asthma. He was introduced to weightlifting by neighbors, including Noboru “Dave” Shimoda, a member of the camp weightlifting and bodybuilding club and brother of actor Yuki Shimoda. After being released from camp, Kono graduated from Sacramento High School.

“With 3½ years behind barbed wire compound with military sentries posted in watchtowers and living in barracks, I felt socially out of place when I returned to my hometown after the war,” Kono wrote on tommykono.com. “I was 15½ years of age and returning to “civilization” was almost like an immigrant setting up a new residence …

“Before returning to my hometown, I had a year of weight training behind me so my strength level had improved and filled out to some extent my skinny body. That gave me more confidence.

“Training with weights and reading the monthly Strength & Health magazine did much to influence me in a positive way during my high school and junior college years. From the senior year of high school when I entered my first weightlifting contest, I improved so rapidly that within 26 months, at the Pacific Coast Championships, I had made the highest total (780 lbs.) in the world of anyone in my bodyweight class. The 1950 World Championships was won with 777 lbs.

“I missed making the 1950 U.S. World Championship Team because three days before the Team Try-out, my mother passed away; so instead of competing in the Trials, I flew back home.

“The following year I was determined to improve my lifting even more but the Korean Conflict called me to military service. This curbed my weightlifting training completely for military ‘basic training’ allows no time for any other activity for 11 weeks. After my basic training, I took the option of becoming a cook in the Army so I could cook every other day and be able to train on my off-duty days.

“This worked fine until the North Koreans started to target the cooks. The U.S. Army was known to ‘move on its stomach’ and without warm food it was assumed the Army would be demoralized.

“I reported to Camp Stoneman where the troop gathered to be sent overseas, but, in reporting for duty, I was informed that I was taken off the list because I was ‘a candidate for the Olympic Team.’ I suspect someone like Coach Bob Hoffman must have put in a good word for me in Washington, D.C. That gave me the opportunity to make the 1952 U.S. Olympic Team.

“Evidently the U.S. Army thought I’d be of better service to the U.S. at the Olympic Games than ‘up front’ as a cook. Anyway, what could have been hazardous duty of war was now turned to a mission of representing the U.S. on the international stage at the Olympic Games.

“I won the gold medal at the Helsinki Olympics, but my military orders received just a few days before my competition date notified me to be stationed in West Germany for the remainder of my military term to fulfill my overseas duty.”

Kono participated in weekly weightlifting competitions in Germany, eventually equaling or exceeding the Olympic record total of 880 pounds. He returned to the U.S. and was discharged from the Army in 1953. He later moved to Hawaii, which was his home for the rest of his life.

In addition to his accomplishments as an athlete, he made his mark as a coach. He was the Olympic coach for Mexico in 1968, bringing lifters to the Games from a country that had little history in the sport of weightlifting before his arrival. He went on to coach the West German Olympic Team in 1972, and returned to the U.S. to coach its Olympic Team in 1976.

He continued to coach U.S. teams for decades, being selected almost by acclamation to lend his vast experience to the U.S. team at the inaugural Women’s World Championship in 1987, a competition that set the stage for the inclusion of women weightlifters in the Olympics (which happened for the first time at the Sydney Games in 2000).

Kono gained a worldwide reputation as an official in the International Weightlifting Federation and was one of the sport’s most prolific writers, photographers, and equipment designers. The now-defunct Strength & Health magazine featured his seminal training and technique articles (such as “Quality Training”), his photographs (such as one of Gennady Ivanchenko doing high pulls), or the products that he has designed (such as neoprene knee bands). His joint bands are worn by international competitive weightlifters on their knees and elbows.

“My basic personality did not change because of the added experiences and exposure, but I did learn one thing: we should all strive to keep improving ourselves no matter what happens and that adversities and objects are there to challenge our mettle and to make us better, stronger persons,” he wrote. “It is in accepting that challenge that makes us persevere for the bigger goals of life.

“Making excuses or looking for excuses get you nowhere, but finding the solution to a problem is what weightlifting (and life) is all about.”

Kono shared his life lessons in two books: Weightlifting, Olympic Style, which covers lifting technique, training programs, and contest preparation; and Championship Weightlifting, which covers the mental and psychological side of Olympic weightlifting.

* This article was originally published on The Rafu Shimpo on April 29, 2016.

© 2016 The Rafu Shimpo