At first they were dekasegi , people who migrate to work and save with the purpose of returning to their land. 25 years later, the Peruvians who began to migrate to Japan when hyperinflation and terrorism were destroying the country are no longer temporary workers, but immigrants.

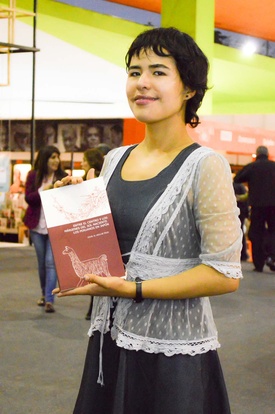

What balance can be made of a quarter of a century of history? Various books and studies have been published about Peruvian immigrants in Japan. The most recent is the work Between the center and the margins of the Rising Sun. Peruvians in Japan , written by Dahil Melgar, a Mexican anthropologist of Peruvian parents.

As part of his research work, Dahil spent two and a half months in Japan, where he interviewed Peruvian immigrants. Through her studies in Mexico, she was familiar with the reality of the Nikkei in her country, but in the case of the Peruvians she discovered a diverse community.

He met Nikkei who constantly claimed their Japanese origin as jealous guardians of their identity; to others for whom the fact of being one was unimportant and the term “Nikkei” was foreign to them (“for different reasons: many generations had passed, it also had to do with the fact of whether the mother was Nikkei or not; finally they are the mothers who have a more important role in the process of transmitting culture and traditions," he explains); as well as some, especially older people, who told him that they had been discriminated against for not having Japanese ancestry on both sides.

He met with Nikkei who told him that when they lived in Peru they felt special, as if the mere fact of having Japanese origin gave them a status superior to the rest. “They even told me 'I didn't understand that I was Peruvian until I traveled to Japan.' I was in Peru and I didn't think I was Peruvian. I was born in this country, but I didn't feel part of this country,” he remembers. Being Nikkei for them was “a reason for distinction.” However, Japan, by treating them like any foreigner, changed the way they were perceived.

“Some told me 'I thought they were going to treat me very well because I was of (Japanese) descent and I was going to have a better status.' I arrived and they treated me as if I had never had a Japanese mother, a father, a grandfather, a great-grandfather.' That hurt many, to feel that they were not given preferential treatment.”

THE SECOND GENERATION

The vast majority of Nikkei who migrated to Japan were not fluent in the Japanese language. This made it difficult for them to integrate into society and the possibility of leaving the factories and accessing better jobs. Their children, born in Japan or raised in that country, theoretically bilingual and better prepared, would represent a qualitative leap in the evolution of the Peruvian community in Japan.

However, the work of the Mexican researcher reveals that this has not necessarily been the case.

Dahil presents the case of two girls who studied primary school in a Japanese school and, simultaneously, took a Peruvian distance education program because their parents planned to return to Peru. Once their savings goal was reached, the entire family flew back to our country.

However, the distance education they received in Japan was not good. Furthermore, his command of Spanish was poor. They were not prepared to study in a school in Peru.

Years later, the family had to return to Japan due to their critical economic situation. The girls also did not master nihongo and were not qualified to reintegrate into the Japanese educational system. Thus, at 15 and 16 years old, the teenagers stopped studying to work in the same factory as their parents.

The success stories that the Mexican found corresponded to children who had followed the Japanese school system. They were the ones most likely to enter college and get a better job than their parents.

In contrast, those who followed the Peruvian educational system, excluding Japanese schooling, were less likely to improve their parents' status.

Bilingual or single language education? There is no recipe. “Each case is different. The only real cases that I saw of having only attended the Peruvian school were of people who stayed for two or three years and returned to Peru, which was very clear that (Japan) was not their destination. But the people who were irresponsible, in the sense of saying 'one more year, one more year (I'm staying in Japan)', were the ones who created the most difficulties for their children. If someone is uncertain about whether or not they are going to return (to Peru), the best thing is to put them in a Japanese school.”

There are people who have been in Japan for a long time who want to return to Peru and promise to do so within a year. However, for various reasons – especially economic – it does not do so. The self-imposed deadline – “one more year” – is extended indefinitely, harming their children by keeping them in a kind of limbo.

Another problem that the anthropologist detected was, especially in the children of the first immigrants, that in Japanese schools students automatically pass the grade. As many climb through the Japanese educational system without necessarily being prepared, when they reach higher levels they crash against the limitations of their insufficient training. Without the possibility of pursuing a university degree, at a young age they have to go to work.

However, Dahil believes that the situation will improve with the third generation, the grandchildren of the immigrants.

"I feel that it is not going to be a chain, 'we will remain workers forever, our grandchildren and great-grandchildren.' I believe that the significant change will be for the third generation, I believe that it is the one that will achieve a more successful insertion, as an ordinary Japanese. It will depend more on your own abilities as an individual to achieve all the success that is within your reach. I feel that the second generation, those who were born there (in Japan) or migrated very young, were not necessarily able to choose their destiny. Nor was it their responsibility to study every year, with such young children the responsibility is more on the parents than on the child himself. They aren't exactly responsible for whether they succeed or fail; If they succeed yes, but if they fail no. “Now in the third (generation) it will be up to each individual.”

THE LANGUAGE, PENDING SUBJECT. HIS FAULT?

The Peruvian immigrant who does not speak Japanese is often held responsible for his lack of knowledge of the language. Dahil has a different opinion. He says that the Japanese State did not design integration measures for the Nikkei, which would have included promoting language teaching to offer them the opportunity for temporary factory work.

“Although Japanese language classes for foreigners have existed since the eighties, the truth is that sometimes they were not compatible with factory schedules. Sometimes the places where the courses were given were too far from where the dekasegi lived. There was not even the possibility of getting there because he did not have his own car, because by bicycle it was a very long distance or because he was going to spend a lot of money on the train ticket. Sometimes it is usually blamed only on dekasegi, 'you didn't want to learn the language', but I don't think so based on the cases I saw."

She attributes language learning above all to particular situations. He mentions two cases of immigrants who insisted on learning nihongo when they had the opportunity to do so: one lost his job and while collecting unemployment insurance began to study; Another person, after suffering a serious accident at work that required a year of recovery, took advantage of the time to study. In short, in his opinion it is more than anything a matter of opportunities.

However, there were also immigrants who from the first moment made an effort to learn nihongo (socializing with the Japanese in the factory, watching television, etc.) and they succeeded.

In many cases (perhaps most) the initial plan of staying only a few years in Japan and returning to Peru with money saved instilled in the immigrants the conviction that it was not necessary to learn Japanese.

THE OPPORTUNITY NOT TO BE A FOREIGN

“We are gaijin (foreigners), but they have the opportunity not to be,” a Nikkei mother told Dahil, referring to her children. In the case of that woman, bilingualism was not an option for her children. I wanted them to only speak Japanese. With the Japanese appearance, the Japanese surname and their command of the language, the foreign origin of their children would become invisible. Better not to be gaijin in Japan.

Furthermore, there are children of immigrants who resist learning Spanish. Because? Because they want to hide their foreign origin and avoid a possible return to Peru. In the book its author reveals:

“A father told me how, after his children's first trip to Peru, they were so shocked by the poverty, the dirty streets and the stray dogs, that, from then on, they refused to speak Spanish, to the point of forget it completely.”

The Peruvian community could be diluted. “I think it may be a migration that fades away. As it is an ethnic migration (the majority are descendants of Japanese), the day one becomes one hundred percent integrated, it disappears phenotypically, that bodily imprint no longer remains. A family told me that they had raised their children as Japanese, they only spoke Japanese because they wanted them to be Japanese, and they knew that because of their face, their last name, they were not going to be detected (as foreigners),” he explains.

On the other hand, if Japan was decisive for many Nikkei to discover that they were Peruvian and not Japanese, it also contributed to their understanding that values – such as honesty – are not intrinsic to any human group. Those who believed that a person, just because they were of Japanese origin, was honest or honest opened their eyes in Japan.

“The migration demystified that every Japanese was honorable, correct,” says Dahil. There were Nikkei who did not conceive that the agency that employed them, because it was Japanese, could deceive them. A Nikkei who discovered that his contractor was making improper deductions from his salary told him: “That's when I realized that the Japanese could also steal.”

There are Peruvians who thank Japan for the opportunity to find a way out when Peru was suffering from hyperinflation and terrorism, and to buy a house, open a business or educate their children. They also appreciate civility and order, aspects in which Japan excels worldwide. “I've never heard anyone say that they haven't learned from their time there (in Japan),” Dahil says.

However, among some he found “a strong resentment of knowing that they were discriminated against, of not knowing that they were valued, in the sense that you spent twenty years without having the possibility of doing another type of work, or of knowing that you were subjected to undesirable jobs, "very hard, very dangerous jobs."

And what does the future look like? Will immigrants permanently put down roots in Japan? Will they return to Peru? There were people who told him: “I am staying here, especially because my children no longer want to return to Peru and I am not going to separate myself from my children because it is the only family I have left.” However, others told him: “I'm waiting for my children to be older and bye, I'm going back.”

DATA

- In 1990, the Japanese government established the teijusha visa for people of Japanese descent with the aim of covering the labor shortage in its factories, encouraging the mass migration of Peruvian Nikkei.

- It is estimated that around 50,000 Peruvians live in Japan.

- Peruvians form the most important Spanish-speaking community in Japan and the second in Latin America after Brazil.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 100, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2015 Texto y fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa