Going back to the pre-Redress days then, can you trace your involvement with the Japanese Canadian community in Winnipeg and beyond? When and how did it begin? Who were the leaders back in those early days?

My leadership began early. When I was 15, I organized a hockey team in our area of the city that was very poor. I coached hockey for a number of years and enjoyed organizing other sports such as baseball and football teams. When I entered education I felt that my experience with young people was an asset and felt very comfortable with that role.

When I was a teacher in the Transcona-Springfield School Division I ran for vice president of the Teachers Association and the following year in 1970 I became president. This provided me with leadership skills that were invaluable as I became an administrator.

Throughout my career as principal I atended dozens of leadership conferences and courses. At the same time, I was involved with the Japanese organizations as well. All of this helped me in my role as president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC).

Winnipeg has maintained a strong vibrant JC community because the majority came around the same time to work the sugar beet farms. In order to assist the isolated families who were ill-treated by a farmer or who faced poor living or working conditions, the first Japanese Canadian organization after the internment was formed by Harold Hirose, Tom Mitani, Ichiro Hirayama, and Shinji Sato to negotiate with the BC Securities Commission on behalf of sugar beet workers. They had to meet secretly to avoid possible reprimand from the authorities.

I believe that the collective experiences of the first arrivals have resulted in an active cohesive Japanese Canadian community because of the need to support and assist each other as they made the transition to Winnipeg from the farms. Although we had a Buddhist and United churches, the members of both churches supported each other’s activities. The present Manitoba Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association (MJCCA) was established in 1946 to provide social activities, services, and assist claimants with the Bird Commission applications.

I joined the MJCCA Board when I was 26 years of age. At that time, meetings were conducted mostly in Japanese so I relied on the Niseis to translate for me as I didn’t speak Japanese. I first became president in 1968 for two years and then later on I was president. My first exposure to the national Japanese scene was when I and Naomi Kuwada represented MJCCA at Japanese Canadian Centennial Society and helped organize activities in Winnipeg to celebrate the Centennial year. I also was the representative for MJCCA at the National JCCA meetings and continued that role until I became president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians in January 1984.

We established a President’s Committee with Winnipeg members to assist the NAJC president. People such as Harold Hirose, Henry Kojima, Lucy Yamashita, Fred Kaita, Alan Yoshino, Carol Matsumoto, and Joy Ooto assisted me with the daily operations.

What were the core issues of concern for JCs during Redress? How was the idea of Redress received by the Issei? Nisei?

There were two issues that we had to contend with early. The first was to convince our community to support the redress campaign. There were concerns and fears within the Japanese Canadian community that by undertaking this redress movement they feared backlash and racism. Many felt that seeking redress was a futile effort for a small community of 60,000 people who had very little political clout. With the feeling that redress was not attainable, it was difficult for many Japanese Canadians to support NAJC’s redress mandate. For many the reluctance to talk about their past that brought shame, humiliation, and embarrassment was prevalent amongst the older generation. The NAJC had to counteract these apprehensions to gain the support of the community.

The second was to overcome the division within the Japanese Canadian regarding the form of compensation. The NAJC supported individual and community compensation whereas opposing groups wanted only community compensation. We conducted a national survey in 1985 on forms of compensation and there was overwhelming support from the internees for individual compensation.

How did it evolve into a national movement? What kinds of obstacles did the idea of “Redress” have to overcome? It scared a lot of people, didn’t it?

Redress became a national issue because of our close relationship with the media and some contact with supportive politicians. We made contact with the Opposition parties and met with them on a regular basis updating them on what was happening. Every time we had a national meeting to discuss redress we would hold a press conference and get media coverage. I appeared on many talk shows from different provinces and appeared on the CBC TV program Front Page Challenge which gave us national exposure.

The concept of redress meant that we were seeking monetary compensation which Canadians might oppose. However, we placed the emphasis on a negotiated settlement and didn’t talk about the quantum but more on the process. I think this approach tempered possible reactions from the public although we did receive that especially from the veterans and their groups.

What is the legacy of the Redress Movement in Canada?

One of the legacies of the Japanese Canadian Redress settlement is the precedent that it has been established for the government to resolve other past injustices. Since 2005, the Conservative government under Prime Minister Stephen Harper has issued apology and compensation that were modeled after the Japanese Canadian redress settlement to the victims of Aboriginal residential schools, the Chinese Head Tax, the Ukrainian Canadian internment during World War I, and the Aboriginal veterans’.

Recently, an apology was given to the Sikh community by the prime minister for the Komagata Maru incident. The Japanese Canadian redress achievement has had a positive influence for other Canadians and is one that we as Canadians can be proud of.

What other successes can you point to?

The success of redress has had a profound impact upon the JC community. For many individuals, redress helped them come to terms with their identity and their heritage.

One person remarked, ”Since redress, my awareness has grown and also my sense of myself. I feel that it’s easier to walk tall and talk about my culture.” Someone else said, “Redress was important because it had a psychological effect and helped our elders open up and gain peace of mind.” Others have told me that a great burden has been lifted, a feeling of guilt, thinking somehow they were responsible for what happened to them during the war. For many, redress was the beginning of a healing process but one person told me this: “I felt the Redress Settlement was something of a closure for me.”

These Japanese Canadians are now more willing to talk about the past and share their stories with the younger generation and with other Canadians. Pride in Japanese heritage and identity is more obvious amongst Japanese Canadians.

The $12-million-dollar community fund administered by the Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation has contributed tremendously to the revitalization and stimulation of the Japanese Canadian community. Prior to the redress settlement there were only two cultural centres across Canada.

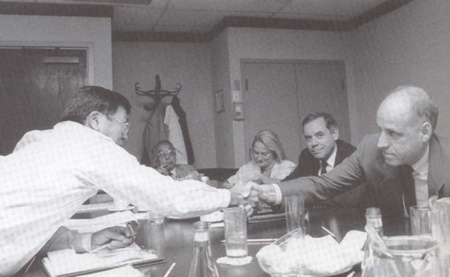

Hon. Gerry Weiner signing the Community Fund Contribution Agreement with Art Miki, President of NAJC, March 39, 1989. Photo courtesy of Art Miki.

Hon. Gerry Weiner signing the Community Fund Contribution Agreement with Art Miki, President of NAJC, March 39, 1989. Photo courtesy of Art Miki.Today, we have 12 cultural and community centres that have become focal places where cultural, educational, and social activities bring the Japanese Canadians together. The increased level of participation demonstrates that there is renewed interest in Japanese Canadian culture and in being Japanese. Programs and activities are being accessed by other Canadians and this relationship has certainly created positive attitudes.

Art Miki with the Hon. Lincoln Alexander, the first Chair of the Canadian Race Relations Foundation 1997. Photo courtesy of Art Miki.

Art Miki with the Hon. Lincoln Alexander, the first Chair of the Canadian Race Relations Foundation 1997. Photo courtesy of Art Miki.The creation of the Canadian Race Relations Foundation or CRRF was one of the final terms of the Japanese Canadian redress agreement but an important legacy for Canadians in general. The Canadian Race Relations Foundation (CRRF) was established as part of the Japanese Canadian Redress agreement and opened its doors in 1996. I was the first vice-president and served for six years. Today, I represent the NAJC on the CRRF Board to ensure that the organization is meeting its mandate as set out by the Act and to orient new Board members on the history and purpose of the Foundation as envisioned by the NAJC.

The Foundation survives on a $24-million-dollar endowment of which $12 million was contributed on behalf of the Japanese Canadian community. One of the important policy issues for the Foundation is to provide moral and research support for groups who have suffered past injustices and or are facing discrimination presently.

In this post-Redress era, what are you most proud of? Most hopeful for?

Many of the things stated in the last comment are things that I’m most proud of. I’m pleased that the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (located in Winnipeg) has the internment experience highlighted and also in the Canadian War Museum. I think we have a ways to go to get our stories in school curriculums and hopeful that will be done.

How did Redress change our JC community’s place in Canada?

Redress has given the NAJC a profile on the Canadian scene for the successful redress settlement. We are looked upon for comments related human rights violations today. I feel that NAJC needs to have a stronger impact in the national dialogue. We need to find strong Japanese Canadian activists to assist the NAJC on their Human Rights Committee. I think most Japanese Canadians are content with their lifestyles and not that concerned about human rights issues.

What is the NAJC’s stand on First Nations issues?

The NAJC has always been supportive of First Nations issues. It goes back to the Stoney Point protests back around 1985. The Stoney Point tribe was trying to get back the original lands confiscated during the war. It was used as an army base during the war and was used as a cadet training base later. The leaders asked NAJC to assist them. We wrote up the proposal for them with the help of Ann Sunahara but nothing came out of it immediately but later I believe they did get the land back.

While I was president I met Ovide Mecredi who became Grand Chief of the Assembly of First Nations. He invited me to meet with his committee looking into residential school abuse and redress after the Japanese redress agreement was achieved. I spoke to the residential school committee in Edmonton. They were at the beginning stages and were having difficulty getting support from their own community. NAJC went through the same thing during our redress campaign such as the division within the JC community. Later when Phil Fontaine was Grand Chief I spoke at their gatherings several times sharing our approach to redress.

In 2004 at Calgary when the government was only looking at situations where sexual or physical abuse took place as the settlement. The approach from the government was limiting so I was asked to speak to a larger group in Vancouver where I spoke about our approach that anyone who was restricted by the War Measures Act and rights violated should be eligible for compensation. They applauded the approach and so Phil Fontaine and group pushed the government to recognize anyone who attended residential schools. That eventually became the approach that the residential school agreement was based on. Roy is presently researching into how the Japanese and Aboriginal situation intersect.

What about the present Syrian refugee crisis?

I don’t believe the NAJC has taken a stand on the Syrian refugee crisis. You should talk to Ken Noma or Bev Ohashi with regard to that. I think we should be making comments as to the parallels of the situation with JCs experienced.

I speak often on the Japanese Canadian experiences to various groups. Two weeks ago I spoke at a Conference organized by the School of Social Work at the University of Manitoba and also to a class of university students from Global College at University of Winnipeg. I speak to several different departments at University of Winnipeg each year. I spoke at University of Brandon last spring and at the Internment Conference in Winnipeg in June. I think it’s important for us to share the stories as I agree that many people are unaware of that part of our history. The NAJC should look at some program encouraging our community to go out to schools and organizations about the Japanese experience. I have done some presentations with the Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg.

When I was Citizenship Judge I shared part of my experiences with new citizens such as Japanese not having the right to vote before the war even though they were born in Canada. I tie that in with the Citizenship Act of 1947 to show that all Canadians were not treated equally at one time. We do have a responsibility to share our stories.

© 2015 Norm Ibuki