Nentaro (also known as Toshitaro or Mantaro) Ide was born in Fukuoka, Japan on October 13, 1867, and according to his internment file, arrived in Hawaii in 1901, where he worked on a dairy farm and lived until 1906, then left for Seattle, where he briefly lived. He then moved to San Francisco and then Concord in 1909.

He was foreman of the Shadelands Ranch, owned by the Penniman family, and also started a hotel and grocery store. Sheila Rogstad, historian of the Walnut Creek Historical Society, now housed at the former ranch, says Ide also supplied many Ygnacio Valley farms with temporary help. According to his questionnaire during World War II, Ide did not attend school in Japan. He was a Catholic (though his file also said he was Buddhist), and he later received a letter of support from the Maryknoll Catholic mission in Los Angeles.

Nentaro and his wife Tsui (née Nakagaki) adopted a child in Japan, who unfortunately died while they still lived there. In 1928, Ide gave all of his property to his niece, in consideration for her taking care of him and his wife, but she passed away so he gave the property to his three nephews, Masatsuji (aka Masaji) Ide, Toshiwo (misspelled “Tisero” by authorities) Ide, and Kumetaro Nakagaki. Toshiwo owned Mantaro Ide’s store and took care of him and his wife; the other two moved to Stockton in March of 1942. By then, Ide had retired.

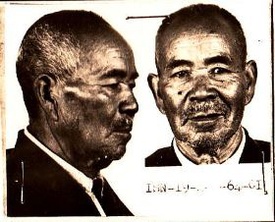

Ide was apprehended in Concord on March 28, 1942, and then sent to the Immigration and Naturalization Service office at 801 Silver Avenue in San Francisco. He was questioned at an Alien Enemy Hearing Board in San Francisco on April 10 at the U.S. Post Office and Court Building in San Francisco; three members of the board, an assistant U.S. Attorney, FBI agent, and immigration inspector were all present.

Ide was accompanied by his friend Ralph Harrison, a deputy sheriff who had known Ide for many years and vouched for Ide’s “honesty, peace, and quietude.” The report noted that “he appears to be an inoffensive, harmless person and on account of his age—now 75 years—and other factors appearing in evidence at his examination, we are convinced that he would be harmless during the war and accordingly recommend his parole into the custody of some person to be designated by the Attorney General.”

The FBI report says he was apprehended because he was listed in a book called The History of Kendo in North America and a confidential informant had notified the FBI that he had operated a fencing school and “even at present he is running a small store and photography establishment in Concord,” which Ide denied. Ide also denied being a member of the Hokubei Butoku Kai, the military virtue society of North America, and stated he had not written to or received any mail from Japan for at least five or six years. Ide stated that the United States was his country and that he hoped the U.S. would win the war. He also denied being a photographer or operator of a fencing school. Because of this testimony and his age, he was recommended for release, but because of his membership in the Japanese Association fifteen years ago, he was still recommended for parole.

Ide was released to join his wife Tsui at the Turlock Assembly Center, then re-arrested, perhaps because of his petition for repatriation on May 18, and sent to Sharp Park Camp in Pacifica on June 10, 1942. He was ordered interned and was transferred to Fort McDowell (Angel Island) the next day and then to Lordsburg, NM, arriving July 5, 1942. He had a physical exam while at Angel Island when he was age 75 and was found to have high blood pressure and rapid breathing, consistent with changes due to age and mild hypertension.

On Angel Island, the Japanese immigrant detainees were not considered prisoners of war, but where they were housed was considered a prisoner of war enclosure. They were located in the same large room as the POWs from Japan, Italy, and Germany, which included a wooden divider down the center (still visible if one visits today). Before his departure for Lordsburg, Ide, like other internees, went through an inventory of his possessions including articles of clothing, writing material, cigarettes, etc.

While in Lordsburg, Ide requested to join his wife Tsui at a family internment center, but before this could happen, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, a form of a stroke, on December 20, 1942, which resulted in partial paralysis of his tongue and, according to government officials, he was in a “semi-delirious condition… [his] prognosis is ‘poor.’” While at Lordsburg, thirteen friends of his advocated on his behalf and on February 12, 1943, wrote a letter urging his release because of his medical condition.

According to a memorandum on March 24, 1943, the unnamed official who reported on his condition noted, “It seems obvious that the board is correct in determining that this alien, in his present condition, could not possibly be dangerous to the security of the United States. There is some chance that if he were reunited with his wife in a family internment center she might help to take care of him in his present feeble condition.” Ide also received a letter of support in May of 1943 to the Department of Justice from Rev. Hugh Lavery of Maryknoll in Los Angeles urging his release.

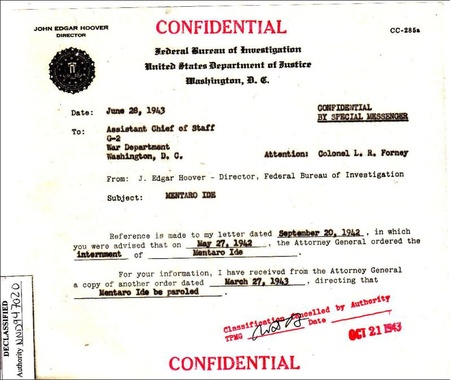

Despite this, he was still sent to Santa Fe, NM on June 16, 1943, and was finally paroled to the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona a month later to rejoin his wife on July 13. A confidential memo from J. Edgar Hoover, FBI director, dated June 28, 1943, mentioned that the Attorney General issued an order on March 27, 1943, directing that Ide be paroled, but it had taken four months for his release to his wife, six months since his stroke. While at Gila River, Ide petitioned for repatriation to his native Japan with his wife and nephew Toshiwo, but because of his medical condition, it was denied.

Ide’s “Alien Enemy” proceedings were finally terminated on November 15, 1945, but he died in March of the next year. According to Ide’s niece Dawn Ide Eames, Nentaro is buried in Concord, California, and Tsui returned to Japan and is buried there.

*This article was originally published by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation.

© 2015 Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation