Most people, even avid followers of Japanese American history, might ask, “Who are the disciplinary barracks boys?” In the seventy years since the end of WWII, little has been written about this group of 21 soldiers who in 1944 faced military criminal trials, dishonorable discharge, and imprisonment in the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. After years of appeals and setbacks, a reversal was finally granted to 11 of them who pursued their cases all the way to the Pentagon. Known as the DB boys, they remained largely out of the public eye until 2012, when author/educator Linda Tamura exposed their complex story in her book, Nisei Soldiers Break Their Silence: Coming Home to Hood River.

These men were in the military at a time when Nisei were refused firearms or helmets because they were not trusted to serve in combat. Due to their Japanese ancestry, they were only permitted the most menial jobs—like shoveling manure, chopping weeds, cleaning latrines, or unloading freight. They were also reportedly under security surveillance.

In 1943, there were roughly 130 Nisei and Kibei soldiers in two detachments at Fort Riley’s Cavalry Replacement Training Center (CRTC) when President Roosevelt visited the base on a highly secret tour. Instead of participating in the festivities to welcome the President, they were ordered to march in the opposite direction by soldiers with machine guns who herded them into an aircraft hangar. The segregated soldiers were then commanded to sit in dark silence for more than four hours as the President’s parade toured the army base.

This temporary confinement resulted in deep-seated enmity between the Japanese American soldiers and the military command. The circumstances culminated when the Thirty-third Infantry Battalion, finally reassigned to combat duty to replace the high number of casualties in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, was to begin training at Fort McClellan. More than a hundred men were gathered at battalion headquarters on the morning of their official welcome on March 20, 1944, to seek appointments with officers to discuss issues of discrimination. Reports of what ensued vary, but as reported by Tamura, “Sergeant Edward McDonald ordered the men to fall in and when several broke ranks (reportedly to protest being called ‘yellow-bellied Japs,’ which the sergeant denied, Major William B. Aycock commanded Corporal Jessie R. Ballinger to march the men to the Field house. After they proceeded about 75 yards, the columns stopped.”

Charges of refusal to obey orders were levied against the Nisei/Kibei soldiers, and 106 of them were confined in the stockade. While imprisoned, they were told they could either train for combat or not. Threatened with consequences similar to actions in Germany or Japan, 28 men still refused, uncertain about their futures. They were subsequently charged with willful disobedience of a lawful order of a superior officer. Eventually, 21 Nisei and Kibei soldiers faced military criminal trials that resulted in dishonorable discharges and federal prison sentences. Not all of the soldiers charged at Ft. McClellan had been at Ft. Riley, but others responded based on their own principles.

What followed was a 34-year struggle by two unrelenting crusaders acting on behalf of the DB boys who sought to correct the longstanding injustice suffered by these men. According to Tamura, Charles Edmund Zane and Paul Minerich were both “novices” whose “personal connections and belief in the severity of the wrongs these men endured really matched the DB boys’ passion.” Zane was a childhood friend of one of the DB boys, Masao Kataoka, and Minerich was a law student—and eventual attorney—who became the son-in-law of another DB boy, Tim Nomiyama. Both spent countless time and energy gathering evidence and writing letters and briefs to tirelessly fight to overturn the governmental charges against the DB boys.

Tamura’s uncovering the story of the DB boys and their plight was an enormous task involving both ingenuity and perseverance. Tamura recalls, “There was almost nothing written about the disciplinary barrack boys at that time so I felt like a detective unraveling a mystery.” (Tamura notes that Shirley Castelnuovo had already written an account in her book, Soldiers of Conscience, but it wasn’t available to Tamura when she was writing her book.) Moreover, Tamura, a Willamette University professor of education emerita whose father was a WWII veteran, discovered early that the issue of those who were dishonorably discharged was an extremely “touchy subject.”

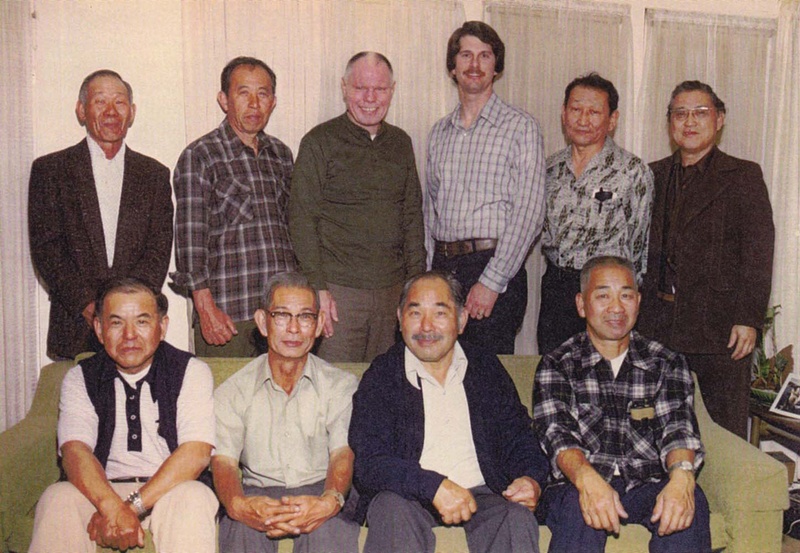

In researching her 2012 book on the Hood River veterans, Tamura found that the story involved a Nisei soldier who had moved to Los Angeles from her native town. “Thankfully, two of the men, as well as a friend of theirs, spoke with me on the phone in 2003 and then agreed to meet with me in Los Angeles in 2004,” she remembered. In addition to the interviews initially with Kenjiro Hayakawa and Fred Sumoge, her research involved “government documents, transcripts of their court cases, military court martial records, military law books,” and more. Attempting to be diligently objective, she notes, “When versions from the military and the men differed—as they typically did—I conveyed both sides.”

There were many reasons Tamura cited for the lack of attention given these men who served time in federal prison much like the more well-known Heart Mountain Resisters. Many of the DB boys, according to Tamura, were Kibei so “language fluency was an issue.” Also, “they were not necessarily outgoing charismatic leaders; they were simply quiet but principled men who endured much discrimination until they’d had enough—so they spoke out. Even though by 1981 they had careers, their ultimate goal was to clear their names. As Tamura describes them, “Hayakawa, a nurse at the hospital ward, was demoted when he arrived at Ft. McClellan although his role was the same. He sought an appointment with an administrator to ask for help with his language difficulties. He was willing to serve in the military but first he wanted to express concern about discrimination his family and he had faced. He was sentenced to five years at Ft. Leavenworth.”

Another interviewee, Fred Sumoge, was a Nisei “who spoke English and, once he overcame his reluctance to tell his own story, was articulate and passionate.” Tamura describes Sumoge as a private man who “spoke out for others who were treated unfairly, but did not seek publicity for himself.”

Eventually, all the DB boys served 25 months in prison. Understanding the anguish they must have endured in their long-term battle for exoneration, Tamura describes their “quiet courage.” “They were not outspoken about their dilemmas, even among friends and family,” she emphasizes. “One family member told me he wasn’t aware of what his brother had endured until he read my book.”

Only 11 of them decided to fight for the reversal of their dishonorable discharges all the way to the Pentagon. Others were either unable to be reached or chose not to participate to maintain their privacy on the issue. First vindicated with honorable discharge certificates in 1980, they sought correction of their military record as well. On December 8, 1982, Minerich presented their case to the Army Board for Correction of Military Records at the Pentagon. Though the Army Board did not set aside their court-martial convictions, they did recommend their military records be corrected, and also reinstated their military benefits. Best of all, the military board concluded that “an injustice” had occurred.

Two of the DB boys, Hayakawa and Sumoge, are in their 90s today. Though Tamura knows that “having been rejected must take a toll on one’s life,” she dug deep in order to know the “confounding aspects of their story.” In doing so, she honored a courageous group of men “who believed so much in the democratic process that they were willing to speak out—gently but fervently—to deal with consequences that lasted 34 years.”

******

A Different Kind of Courage: The Disciplinary Barrack Boys of World War II

At the Japanese American National Museum

Saturday, September 12, 2015

2 p.m.—4 p.m.

Author Linda Tamura, attorney Paul Minerich, and Gary Itano, son of one of the DB boys, will discuss this story in a special public program at the Japanese American National Museum. The event is co-sponsored by Go For Broke National Education Center.

This program is free with museum admission. Click here to RSVP.

© 2015 Sharon Yamato