In Japan, Okinawans have been in conflict with their government over the US base relocation. The word “immigration” may be one of the key words to understanding their unique way of thinking. In Japanese history, there is a missing link—the history of immigration—and perhaps the great majority of people are not even aware of the fact that it is missing from their history. For the Japanese living in Japan, things that happen at the sites of immigration are out of the realm of their concern and not written or taught as part of contemporary history. However, they make up a large part of Japanese history with a subtle yet rather powerful influence.

I will share one example. In a masterpiece by Eiji Oguma, professor at Keio University, The Japanese on Borderline—Okinawa, Ainu, Taiwan, Korea—From Colonization to Fights for Reversion (from Shinyo-sha, 1998, 5,800 yen), he talks extensively about “the Japanese in borderline areas” across 778 pages, yet in its index, there is no mention of “Brazil,” let alone “immigrants” or “Nikkei people.”

When I found an even more gigantic book (priced at 15,000 yen), titled The Directory of Japanese People Who Crossed the Ocean (edited by Hitoshi Tomita, Kinokuniya Bookstore, 1985) with 1,700 names of Japanese people including drifters, students, and street performers who have gone to Western countries from the Edo era to the Meiji era, I got very excited. I was expecting to see many names of immigrants, yet it didn’t even have the name of Ryo Mizuno, known as the father of Brazilian immigrants. Soon my expectation turned into disappointment that I would not find other names of immigrants in it.

Looking at the names of people in the book, I realized that many of them have returned to Japan. Strangely enough, in Japan one has to return home to be considered someone who has “crossed the ocean.” The book was a clear example of the closed mindset of the Japanese in Japan.

Why is there another side to immigration history in the first place? The answer is simple. Those who have moved outside of Japan had some reasons and strong feelings for or against the country. They crossed the borders with their reasons and feelings and no longer received attention from the home country. As a result, for Brazilian immigrants, their history of 250,000 people which accounts for an entire population of a middle-sized city was ignored in its entirety and barely taught in history or geography textbooks until quite recently.

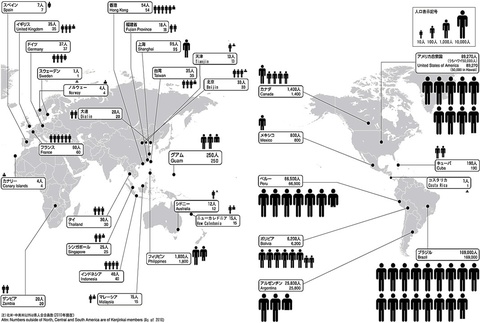

Okinawans Account for 10% of Nikkei in the World

The Brazilian immigration history can be characterized by the vast number of people of “Okinawan descent.” The word ken-keijin (literally, people of prefectural descent) itself is unique to Okinawa and is used in local media such as Okinawa Times and Ryukyu Shimpo. It’s hardly ever seen in other prefectural papers.

In Japan, the population of Okinawa accounts for a little over 1% (1.4 million people), yet it is 10% (350,000 people) of Nikkei people in the world (3.5 million people in total). In the Brazilian Nikkei community (1.6 million people), they make up 10% (170,000 people) of the population, and more than 90% are said to be of Okinawan descent in Peru and Argentina. In short, the population ratio flips in the new land.

Why are there so many people of Okinawan descent? It’s precisely because the island has been a center of historical turmoil in contemporary Japan.

If we look at the number from their side, we see that 350,000 people, out of 1.4 million (the entire population of Okinawa) live outside of the prefecture—which makes the place a prefecture of immigrants with 25% of population living abroad. There is no other prefecture like it.

How did Okinawa become the prefecture of immigrants?

Discrimination and War Made People Move Out

What made people move out of their homeland can be summarized into three factors: their desire for equal society, difficult conditions of economy, and the Battle of Okinawa.

For those who lived in the age of so-called “sotetsu (Japanese sago palm) hell” in the Meiji era where people were heavily taxed and scarcely had food to eat except for sotetsu, moving to a new land meant getting their rights—their way of showing the need for equal society. The first immigrants from the mainland were called “gannen-sha,” who moved to Hawaii in the first year of the Meiji era, and the Okinawans were not allowed to emigrate at first. It took 30 years for them to win the same rights as those on the mainland, and they were finally given such rights in 1899.

In The Chronicle of Contemporary Okinawa, (Kinpuku Arazato, Tatsuhiro Ooshiro, from Ryukyu Shimpo-sha, 1972, pg. 198) there is a line: I found a shocking exhibit in the Museum of Mankind. At the Fifth Industrial Exposition held in Osaka in April, 1903, the museum had an exhibit of “Ryukyu ladies” (in reality they were prostitutes) together with Koreans and the Ainu. Having gone through such discrimination, 325 Okinawans got on the ship Kasato Maru (1908) which carried an approximate total of 800 first immigrants to Brazil. It was immediately after the ban on immigration from Okinawa was removed.

Even in Brazil, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan in 1919 virtually prohibited Okinawans from emigrating, due to their low stability in the coffee farm land, and they didn’t lift the restriction until 1926. In other words, even though they were “late” in starting immigration, the number of Okinawan immigrants soon reached the number of immigrants from the mainland and exceeded it.

According to “The Memorial Magazine of the 90th Anniversary of Okinawans,” 15,286 people from the prewar era (pg. 101) and 6,175 people from the postwar era—a total of 21,461 Okinawans—moved out of their homeland. This accounts for 8.6% of the total 250,000 immigrants.

If we look at those from the postwar era alone, we can see that the Okinawans account for 11.5% of all 53,498 immigrants. This gives us the average number of 1,138 immigrants per prefecture (53,498 divided by 47 prefectures of Japan), with the number of Okinawan immigrants 5.4 times as many as the average.

Without doubt, the Battle of Okinawa was the primary reason for immigration in the postwar era. In the city of Naha, there is an area called Oroku. Surprisingly 4,000 people moved to Brazil from that area alone. The number accounts for 82% of the total number of immigrants from the Shizuoka prefecture, which was 4,881. No other area in Japan had a bigger number of immigrants than from Oroku in terms of its number per surface area.

Why did so many people move out? You will soon understand the reason once you get there. Oroku had the Naha military port in front, the command center of navy in the back, and airports on the sides. They were the target of nasty bombing—as if they dropped two bombs every square meter—in the Battle of Okinawa. Because of that, many people moved to Brazil not only in the prewar era but after the war as well, bringing over their family members.

Kokei Uehara was one of the immigrants from the area who moved to Brazil in the prewar era. Before the war, Grandma, whose brothers had emigrated to the U.S., repeatedly said that Okinawa would be over once the war started and told Kokei’s father to move to Brazil. Reluctantly he sent his children to Brazil. Uehara’s father and sister who remained in Japan died in the bombing even though they were hiding in the bomb shelter. Grandma’s information and decision was right. Those who moved in the prewar era eventually brought over their family members in mass immigration—who went through great suffering in the war—from the homeland.

© 2015 Masayuki Fukasawa