Issei are identified with similar characteristics that Nisei would concur: came to this country with no English skills, no money, dreams of success and possibly returning to Japan. They were hard-working, endured racism and physical abuse, lived through the Great Depression and the injustice of the World War II concentration camps, and bore hardships for the sake of their children, the Nisei, born here in the United States.

The Issei woman was all the above, plus being the smiling, doting grandmother to her Sansei grandchildren, never showed the pain and hardship she endured, even in her personal life. She was religious and had faith in the good that life brought, whether she was Buddhist, Christian, or any other. She supported her family, friends, and community.

Sugi Kiriyama was a typical Issei woman.

Born on December 12, 1889, to Kise, 20, and Kichibei, 21, in Hiroshima-ken, Kamo-gun, Hayatahara-mura, Azana Kazehaya, by the seaside, where the family went to dig clams and to the mountains to pick mushrooms and warabi, or edible fern.

Kichibei made senbei, kuri manju, and yuki manju that they sold at the markets. As they had an abundance of fish to eat, all the villagers were fishermen.

Everyone during Kichibei’s childhood learned at the temple; there were no schools. By Sugi’s time, they had grammar school, and Sugi went as far as the fourth grade, where she learned her kana, kanji, and soroban—the “calculator” of her time. Sugi didn’t like school and was always scolded. She finished her schooling at a home, where she learned sewing, flower arrangement, and tea.

Sugi, at age 17, lost her mother when she caught a cold and died. The following year, she lost her younger sister at age 16 from kidney disease. Her father remarried, and Sugi could do nothing to please her stepmother and was very unhappy.

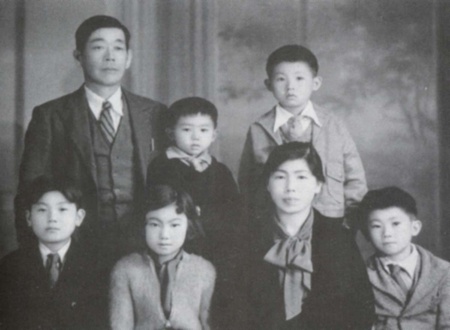

Sugi married Hisataro Fujii when she was 19. Because she was the only child by this time and her father had no Kiriyama heir without a son, Hisataro became a yōshi, the custom of a family “adopting” the son-in-law to carry on the family name. Sugi and Hisataro emigrated to America, docking at San Francisco on April 10, 1914, spending two nights on Angel Island while waiting to be processed through Immigration, then down to San Pedro and Los Angeles.

Sugi worked very hard with her husband, going up and down the coast from Orange County to Fresno to San Gabriel and to Imperial Valley, picking oranges, cotton, olives, strawberries, and grapes. While in Fresno and Imperial Valley, Sugi cooked for all the laborers, numbering 70 in all. In Hollywood and West Los Angeles, she worked at the Kobayakawa boarding house (later called Ishioka) as a cook for the male tenants.

When World War II broke out, the Kiriyama family was sent to Manzanar and then to Tule Lake because Hisataro decided he had to return to Japan at the end of the war to take care of his oldest son’s children. The son, Hideharu, had died prior to the end of the war. Hisataro’s intention was to take the youngest, my husband George, with him to Hiroshima, but Sugi objected and refused to let George go.

While Iwao, George’s brother just above him, and George were children during the immediate postwar resettlement period, Sugi was the sole supporter. Because she could not read, write, or speak English, all she could do was housework or cook in the boarding houses. Later, she worked, cleaning homes, until her 70s. She earned some money by giving massages in her home, although she charged very little and usually accepted money as kimochi, meaning however little the person could afford to give as thanks. Similar to “it’s the thought that counts” in English.

She loved shigin and became a master teacher of the art.

The mainstay of Sugi’s mental and emotional support was her faith. She attended West Los Angeles Buddhist Church and Seicho-no Ie in Gardena. She prayed every morning and night. It would take her a couple of hours each time because she would first pray for her deceased family members and acquaintances, then for all those yet alive! Sugi visited the cemetery every week to lay flowers.

Sugi was always grateful and thankful for everything, in spite of her difficult life. She always had a smile on her face and her hands together in a prayer pose. When redress checks were given to the oldest Issei first, Sugi was among the few that went to Washington DC, to receive her check at age 100. She sat in her wheelchair and had her hands in prayer throughout the ceremonies. Sugi’s pose was an instant media draw as all the photographers focused on her. That picture of her in prayer hit all the D.C. papers, making her quite well known on the streets of the capital. When they boarded the plane back to L.A., a flight attendant recognized her and gave her an airline attendant pin. Sugi told everyone that Washington DC, was the “best place in the world.”

Sugi believed the most important things in life are to go to church, to be kind to others, and to save for one’s old age. Good health and education were also important—although she hated school as a child.

Sugi made the best fried chicken and fried potatoes, which she made in the crusts leftover after she fried the chicken. I think the secret was her old cast iron skillet that was seasoned by decades of frying chicken.

Sugi was strong in mind and body. Well into her 80s, she would walk from home to Yamaguchi Dept. Store, about 3 miles round trip. She had to slow down after she broke her hip. Nonetheless, she managed a mile a day. She passed away at age 102 in a nursing home. She was alert until a few months before. She was probably one of the oldest in the nursing home, but she was the most active of the residents. She loved to play Bingo. One day when we visited, she gave her granddaughter, Traci, a nickel and said, with a serious look, “You know, I once won a DIME,” poking her finger for emphasis.

Sugi really was a role model, living and practicing all the Issei values, and always laughing, always smiling. She never complained or talked about the rough life she had early in her life in Japan and here, in America.

Oh, one other thing that we like to think contributed to her longevity. She liked a shot of whiskey in her coffee every morning. George’s common birthday or Christmas gift was a bottle of the “good stuff.”

* This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices: The Japanese American Family (Volume IV) in 2010. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2010 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California