*Editor’s Note: Frank Abe shared his opinions about Ken Narasaki’s stage adaptation of No-No Boy by John Okada. Ken gave us permission to share his response to Frank’s article below.

* * * * *

I've responded once to Abe's fervent denouncement of my adaptation of John Okada's book and really, just to keep it simple, I repeat: I believe an adaptation is a living thing, that it's impossible to bring the exact same qualities of one medium to another, and it does take some artistry to breathe life into a story that's making that transition. Abe hates my ending; I accept that. But he exhorts the readers to reject the play, and I have to say that again, he did not see it, and he found a draft of the words (they've changed and evolved over time) that he despises so much, but I have to point out again - he may hate the words, but he did not see the two hours of drama that preceded them, nor did he hear the actors saying them in context. At this point, I don't hope to change his mind, but I do hope to keep yours open. The play does its best to bring the novel to life, and I believe it does a beautiful job of doing just that.

Many of the surviving members of the Okada clan came to see the play in Los Angeles and in New York; none expressed any misgivings about the adaptation. The only audience member who voiced a problem with the play to me was a Resistor who wanted me to make Kenji more of a corrupted figure and interpret his death as evidence of the corruption of his having believed the government's lies.

Clearly, passions still run high after all these times, and the book itself is a crucible for those passions, as it always has been, from then 'til now. So, perhaps it's natural that Abe's reaction to my adaptation is so extreme: No-No Boy has always been a lightning rod for the buried rage of so many people forced to accept a horrible reality over which they had so little control. And many of us Sansei have had that buried rage passed down to us.

Ironically, there's an underlying cry for compassion in Okada's books that shines through with the compassion with which he brings his characters and their various points of view to life. And it was that underlying plea for compassion that really made me feel an urgency to get this play produced as soon as possible: So many of the Resistors, the No-No Boys, and the Vets were and are dying now, and it was my hope that a production could bring some small rapprochement. There was some anecdotal evidence after the production in LA that that sometimes happened. Another great outcome, by the way, was how many people came up to me and said they had no idea their uncle, their grandfather, or even their fathers, in some cases, were No-No Boys until they decided to get tickets for the play. So I remain happy that it was produced in LA and New York and I'm still hopeful that Pan Asian will be able to mount a national tour sometime soon.

In many ways, Okada's book was an indictment against the kind of divisive dogma that was splitting the Japanese American community back then - divisions that lasted a generation. Art, on the other hand, can open up our minds...if we let it. Be cautious with people who would like to close your mind for you. If you get the chance to see a production of the play, go ahead and see it, and make up your own mind. I promise you, it'll be worth it.

* * * *

Here is a play review of No-No Boy by Paul Birchall on LA Weekly on April 1, 2010.

GO NO-NO BOY

Grief and bitterness are the unspoken but constantly present co-stars of playwright Ken Narasaki's compelling drama, adapted from John Okada's classic Asian-American novel.

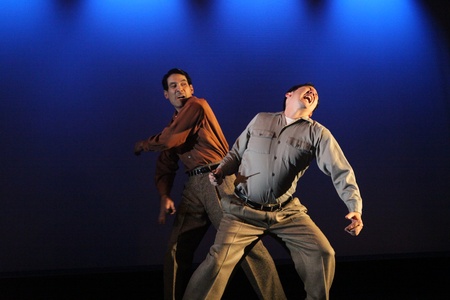

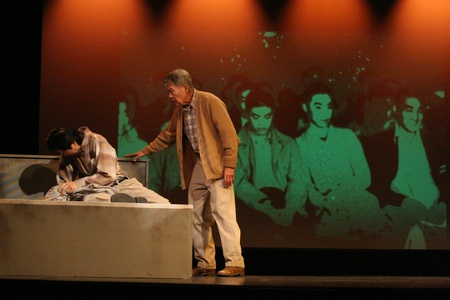

At the end of World War II, second-generation Japanese-American Seattle teen Ichiro (Robert Wu) is finally released from U.S. prison, where he has served time for refusing to participate in the draft. Ichiro's refusal to join the U.S. Army has nothing to do with cowardice. Rather, his choice is the result of being torn between his beloved American upbringing and his Japanese cultural roots. When he returns home, however, he finds wreckage and bitterness where he once had friends and family. His Japan-loyal mother (Sharon Omi), who drove Ichiro to make his choice, lives in denial and has nearly lost her mind, supported by Ichiro's stoic, sad-faced father (Sab Shimono). Ichiro's former best friend Kenji (Greg Watanabe), despite coming home from the war horribly crippled, is more accepting of his buddy's choice. Assisted by Narasaki's deft dialogue, exchanges that belie the depth of fury and bitterness over the American dream turned sour, the play presents characters whose piercing suffering becomes eloquent.

Director Alberto Isaac's deftly subtle production never overplays its emotional hand, opting instead for an understated melancholy that is both elegant and searing. Few dramas have as effectively depicted the sense of being torn between two cultures in a time of war — along with the unique Japanese-American tragedy arising from being simultaneously victorious and defeated. Wu's devastating boy-next-door turn as Ichiro depicts a figure desperately torn between his American upbringing and his Japanese cultural roots — and who discovers that both bring little but sorrow. Other ferociously moving turns are offered by Shimono's pained but undemonstrative father and Omi's brittle, hate-filled mother.

*Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of Discover Nikkei and the Japanese American National Museum. Discover Nikkei is an archive of stories representing different communities, voices, and perspectives. It is intended as a space to share different perspectives expressed within the community and to invite open dialogue.

© 2015 Ken Narasaki