Artist Laura Kina is one of two artists featured in the new exhibition, Sugar/Islands: Finding Okinawa in Hawai‘i—The Art of Laura Kina and Emily Hanako Momohara.

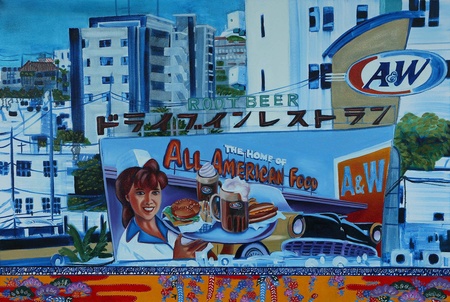

Sugar/Islands explores Japanese American family history and identity through visual art. Kina’s contribution to the show includes a series of striking, ghostly paintings that were inspired by female Okinawan immigrant workers.

Discover Nikkei had the opportunity to engage Kina for a brief conversation about her work.

* * * * *

DN (Discover Nikkei): I read that you tend to approach your work first with the primary aim of creating a good painting, and that the sociopolitical aspects are present but are usually more subtle, in the form of textures and feelings. Can you elaborate a bit on those textures and feelings? What feelings and whose feelings were you thinking about when creating these beautiful but haunting images?

LK (Laura Kina): The sociopolitical is at the heart of my work. These are works about women’s history, about labor and migration, about World War II, about being Uchinanchu (part of the Okinawan diaspora), and about transnational connections between Hawai‘i and Okinawa. That content matters an awful lot to me. When I start working on a series, the initial inspiration is often from an emotion or strong impulse that then might take years of research but then when I’m finally in the studio making work, it’s really affect that matters and responding to the physicality of the paint. I’m not interested in mere illustrations of history or telling people in a didactic way what my politics are. I want to reanimate the past, to feel it, so that it matters for our present moment.

My use of the color blue in the Sugar series (and the related works in my Blue Hawai‘i exhibition) was inspired by the indigo-dyed kasuri kimonos that the Issei (first generation) “picture bride” immigrants repurposed into canefield work clothes. I was fascinated by how their work clothing mixed ahina (denim) and a patchwork of old kimonos and also recycled cotton from rice bags. The clothing reminded me of Japanese boro quilts, a patchwork quilt form I have used in my previous Devon Avenue Sampler works about the hybridity of living in a South Asian/Jewish community in Chicago. For Sugar, I was also drawn to learn more about the bold geometric indigo blue hajichi (Okinawan tattoos) that the Issei generation had on the backs of their hands. Blue is also symbolic of ghostliness and a feeling of melancholy, which are themes that run through the work.

Besides a curiosity in hajichi and sugar plantation work clothing, the Sugar series started from a feeling of melancholia that I recognized five years ago just as I was attaining all of the socio-economic dreams my great-grandparents had hoped for when they immigrated from Okinawa to Hawai‘i in the early 20th century. I’m a college professor, I’m married to a white Jewish man (although I doubt they had that in mind!), and we have a 10-year old daughter and Mitch, my husband, has a 20-year old daughter who is mixed-Mexican American. We have two dogs, a house, and two cars. So I have this middle class urban professional life and yet despite all of this I have felt this huge sense of loss about “making it” and assimilating into whiteness (or near whiteness). In this new space there was also a huge void and multiple erasures. I don’t speak Uchinaguchi, Japanese, or even Pidgin English. No one talked about World War II and the Battle of Okinawa or how that impacted our lives. The sugar plantation world in Hawai‘i that my father grew up in no longer exists and the artifacts and stories from this time period were either absent from my life or not in any order that made sense to me. It was as if I found myself being pushed by this giant wave towards an idea of success and assimilation into the dominant culture and I never stopped to look at or question the forces that were generating the wave in the first place. I began to question the toll living the “model minority myth” has had on my life.

“What are you?” is often the first question I get. As a mixed-race person, my identity has also always been something that people ask about, remind me of, or interrogate me on. When I was a kid I’d say, “Half Japanese, 1/4 Spanish-Basque, and 1/4 French, English, Irish, Scottish, and Dutch.” From the way I look people assume I’m Latina and this just doesn’t reconcile with what people think “Asian” is supposed to look like. Also Okinawans don’t look like what people in the U.S. think “Japanese” is supposed to look like in the first place. So I’ve always carried this feeling of being inauthentically Asian in general and specifically as a failed Japanese American. I grew up with my mom’s side of the family, but even though my dad’s mom lived with us while I was growing up I needed to connect with my Okinawa culture or my father’s community and family in Hawai‘i and Okinawa beyond just eating spam musubi and occasional family reunions. This was something I needed to reconcile on a personal level and then through that I began to understand some far larger histories of colonization that have impacted our lives and that these voids and “failures” were actually quite important.

DN: You mentioned obake (Hawaiian ghost stories) as one of your influences. Can you comment a bit on how you became familiar with obake and how it resonated with you?

LK: I didn’t know about obake growing up, or at least I didn’t use that term. I grew up in an evangelical Christian faith in my parent’s church (I’ve since converted to Judaism) and there was always an understanding of the spirit world being present at all times—the Holy Ghost, Jesus, God, but also evil spirits, demons, and such. I came to imagine these epic spiritual battles swirling around us on a parallel plane as we go about our daily lives. We also lived in a forest in the Pacific Northwest (outside of the Seattle area) and there is just a whole other sense, when you are literally immersed in nature, of a spiritual realm that seems so real, so physical. I remember both my dad and my Grandma Kina telling me that on their sugar cane plantation in Pi‘ihonua there used to be an old graveyard near Camp 5 and at nighttime you could sometime see hinotama (fireballs) shoot out from the graves. My dad saw an orange fireball shoot from the graveyard once and up into the air across the fields. This was a natural phenomenon that occurs due to gases building up inside the grave. Of course as a child, he thought this was a spirit or a ghost! That idea of traces of our ancestors was, no pun intended, the spark that got me started on this journey. I went back to Pi‘ihonua with my dad to talk to elders in the community about the ghost stories they heard as kids.

Going into the Sugar project I had two big misconceptions: (1) that the Okinawan and Japanese picture brides were these passive victims of history; and (2) that Okinawans in Hawai‘i would have Japanese style horror obake stories (I have to admit I’d read way too many “chicken skin” and obake stories by Glen Grant).

What I found that was that the Issei women, according to the stories from the Nisei and Sansei, were tough and had a lot more agency than I expected. Stories even came out that my great-grandma was a bootlegger! I was also surprised to hear how many of the Nisei women went off to college on the mainland and then returned to go into professions like teaching. While some of the ghost stories the elders told me were about were in fact scary ghosts like Kimotori—the liver-taker who would eat your liver if you took too long crossing this one bridge that the kids had to go over to and from school (this was really a ploy to get the kids to come home fast)—most of the stories were not about ghosts being scary but were interwoven with Native Hawaiian mythology emphasizing respect for the dead and knowing what was kapu, or forbidden. “Even if you don’t believe, it’s best to show respect,” they told me. More importantly, over the five years of my research and all of my inspired moments of painting the Sugar works have happened in the month of July/August. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this is also when Obon happens (except for it’s also when I’m off from teaching!).

In the first group of Sugar paintings I did in 2010, which were in a small solo show at Women Made Gallery in Chicago, I was thinking about obake in my head in an intellectual way, just processing the stories I’d collected from Hawai‘i and looking at old photographs. Then in the summer of 2011, I began working on the Issei painting, which I thought was my great-grandma Makato Maehira (my grandmother’s mother) and that painting felt more like it painted itself into existence. I had a strong sense of my ancestors presenting themselves to me; it was Obon after all. Then in July 2012, I brought printed photographs of this painting back to my extended family as omiyage (gifts) in Okinawa. It was my first journey back in over a decade. Family members in Okinawa instantly recognized the picture not as my great-grandmother but as my great-great-grandmother who was my great-grandmother’s namesake. She had been killed during the Battle of Okinawa, along with three other relatives, and her body was never found. My father’s second cousin, Hideo, and his wife Reiko, took me to the family butsudan (Buddhist family shrine) of the #1 son of the Maehira family where her photo resides. That was an incredible experience.

Then from there I began to meet all of our extended family in Okinawa and I’ve since returned several times, including one trip with my dad, which generated the inspiration for rest of the series Sugar and Blue Hawai‘i works. Now I’m even leading Study Abroad trips to Okinawa through DePaul University. We went in 2013 and are planning a trip again for December 2015. That Issei painting was really the key not to just opening up the past to finally talk about some very big unresolved traumas that continue to impact our lives, but to also beginning relationships with my extended family in Okinawa in the present.

DN: What are you working on now?

LK: Too much! This summer I’m finishing co-editing a multi-author volume, Que(e)rying Contemporary Asian American Art, with art historian/curator Jan Christian Bernabe. Our book should be out in 2016 with the University of Washington Press. In addition to our joint intro and essays written by both of us individually, Que(e)rying features six invited author essays and 17 featured artist interviews that all focus on contemporary Asian American art practice, history, and criticism. The title plays on both the act of moving away from “normative” centers through the lens of “que(e)rying”—a framework borrowed from queer theory that brings into relief Asian American differences and their locations within art practices and experiences in our contemporary, globalized moment. Coming out of my last book project, War Baby/Love Child: Mixed Race Asian American Art (University of Washington Press, 2013), I wanted to focus more on how gender and sexuality intersect with issues of race. I’m returning again to think about issues of failure and the creative possibilities in lives and bodies that don’t fit into notions of normativity.

I’m also finishing up illustrating a children’s book written by Lee A. Tonouchi, a.k.a. “Da Pidgin Guerilla” (Lee writes in Pidgin English!). The book is called The Okinawan Princess and it’s set in Hawai‘i in the 1980s (Lee’s childhood and also an excuse to include mullets and ’80s pop culture), plantation era Hawai‘i, and in ancient Ryukyu Kingdom days. It’s about the history of hajichi tattoos. It’s going to be amazing. Lee and I were working on this in December 2014 in Hawai‘i and I need to return to finish that work.

Finally, I’m making all-new work for a solo show, Uchinanchu, which is scheduled for February 27–April 23, 2016 at Cal Poly Pomona’s Kellogg University Art Gallery. This show will feature textile-based constructions/paintings about Okinawan diaspora identity. I’m taking the transnational themes from our Sugar/Islands show of looking at Hawai‘i and Okinawa but these new works are set in the present moment, include content about my life in Chicago and childhood in the Pacific Northwest, and will rely more on telling stories through materials, symbolism, juxtapositions, and overlaps than on oral histories, specific narratives, and photo-based works of my Sugar series.

* * * * *

Sugar/Islands: Finding Okinawa in Hawai‘i is on view from July 11–September 6, 2015, at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

© 2015 Japanese American National Museum