“Don doro don don, Don doro don don, Don doro don don, Don doro don don….”

Nine of us are onstage at the Tacoma Buddhist Temple, a bachi in each hand, each one with our taiko drum and stand. Our group is having a taiko demonstration and class from Wendy Hamai, one of the founding members of the Tacoma Fuji Taiko. The class had been arranged for my daughter and her Girl Scout troop, but Wendy asked us if we—the mothers—would be interested in playing, too.

And so there we were, three moms and five fourth grade girls. Most of us with very little knowledge of taiko, much less experience playing drums. Wendy gave us a very brief discussion of taiko history, and connected it to the girls—I didn’t know this myself, but over half of the taiko players in the United States are women. Wendy brought out a few stethoscopes, so the girls could listen to their own heartbeats as a way to begin to connect to the rhythm of taiko. She talked about kiai, the ways that taiko players chant during performance. She asked the girls to try making sounds, a loud “Hup!”, but at first the girls were uncharacteristically shy, even the ones used to performance.

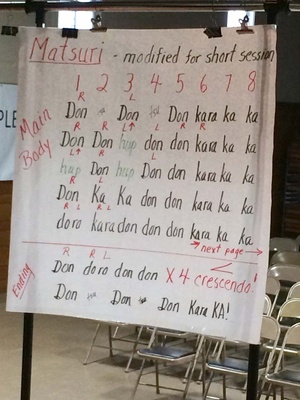

It wasn’t until the girls had bachi in their hands, until they started playing the drums, that they really began to get excited. Wendy took us through the different kinds of “notes,” the sounds made by striking the center of the drum (“don” and “doro”), the sounds made by tapping the rim of the drum (“kara” and “ka”), and a few others in between. Then to my surprise—we only had an hour left—she began to teach us a commonly known taiko song, “Matsuri,” which she had adapted for our group. We practiced the notes of each line until we were able to end at (about) the same time. During a short break one of the girls stayed by her drum, wide-eyed with delight, holding her bachi up to frame her chin. That’s when I knew they were starting to have fun.

All the same it was hard, hard work that we were cramming into this hour. Wendy asked us to practice over and over. We had to practice vocalizing part of the song, called the kiai. We were all staring hard at Wendy’s poster where she’d handwritten the music (she’s found it easier to teach people with a written form, although she noted that not everyone prefers written over an aural tradition). Then she asked us to play faster. We repeated a line that seemed to cause problems. When we didn’t end the song at the same time, she made us do it again. Then she relaxed a bit, and laughed. “There’s a group that comes to my monthly open taiko sessions, and one year they made up a song for my birthday that ended in ‘Whee!’” She looked at the girls. “Do you guys want to add “Whee!” to the end of the song this time?”

“Yeah!” shouted the girls. So we practiced the song for the last time that day, with a repeating crescendo: “Don doro don don, Don doro don don, Don doro don don, Don doro don don….” And then the final line, “Don tsu, Don tsu, Don kara ka—Whee!” And we ended—all at the same time!—with our arms in the air in a triumphant V.

Flashback: I am in first or second grade, and my dad is standing in front of a cafeteria full of kids at my elementary school. He’s dressed in one of his navy blue yukatas, he’s got tabi and straw zori on his feet, and he’s in his element: he’s performing. There are a couple of tables at the front of the room with all kinds of Japanese things: a doll, some chopsticks, maybe a carp flag, Japanese platters, maybe even a rice cooker. He’s placed a few coins inside his yukata sleeves, and is making the sleeves jingle: “Do you know what’s in here?” he asks us. “Money!” we yell. He knows his audience. We’re waiting to see what he shows us next.

I’m in the audience too, and I’m excited—that’s my dad up there! This Japanese stuff is pretty cool! He’s talking about something that I already know! I’m Japanese too!

I don’t know much about the path my dad took after camp, after an adolescence of wartime incarceration at Tule Lake, racial discrimination when he and his family returned from camp, a stint in the U.S. Army at 21. By the time I was born in the early 1970s, the country had come through much of the Civil Rights Movement. By the time I was in elementary school, we were experiencing a Roots era of ethnic pride in cultural traditions. We had shoji screens in our house, and while they faced inside—you couldn’t see the wood framework from the street—they were the first thing you saw as you walked through the front door of our house.

That sense of claiming part of myself as Japanese is really a mix of feelings: excitement, pride, claiming home, gratitude. But now as a parent, I have a sense of how very hard my dad worked for that pride, how very lucky I was to be born then and there. How much he worked for it: playing records in Japanese, translating a song so that my Brownie troop could sing it in Japanese and English at the mall, and eventually taking us all to visit his mother’s family in Japan. How much he worked for that pride, how it was probably hard for him to have it himself, the price he paid to not assimilate completely but to own his own Japanese heritage. How hard he worked not only to remember and claim his Japanese heritage, but to be eager to teach it and share it with others. How I understand more of the triumph represented in being able to teach his granddaughter taiko; how much I appreciate him now.

© 2015 Tamiko Nimura