“The general term strandees, as applied to American citizens of Japanese ancestry, refers to those persons who had gone to Japan and who for various reasons had not returned to the United States before the outbreak of WWII.”

—Frank F. Chuman, The Bamboo People

Whether through one’s own parents or grandparents—or through media such as books or film—many readers of this article are at least familiar with, and grateful for, Japanese Americans having shared their painful stories of incarceration in camps during WWII. An often neglected perspective of Japanese American history, however, is that of U.S. citizens living in Japan when the U.S. entered WWII.

Enter mother and son filmmakers Mary McDonald and Thomas Mazawa who undertook this important Nisei Stories of Wartime Japan project, in part, to fill a gap in the retelling of the Japanese American story. Mary modestly explains that “[t]he relocation camp story is extremely important, but it is not the only story of Japanese Americans during World War II. A couple of people have asked me if I am trying to show that the Nisei in Japan were worse off; but I don’t think anyone should make any judgments about that. I think of it as just another circumstance where JAs had to make the best of things.”

Mary is quick to add that, since so few people seem to be aware that several thousands (up to tens of thousands) of U.S. citizens of Japanese descent had to remain in Japan during WWII, she was primarily focused on telling that story. To that end, Mary reflects, “One comment that added to my resolve to make the film was when Taz Iwata said, ‘No one knows about us.’” Taz is one of the strandees who graciously took time to share some personal experiences for this film.

Another moment that “motivated” Mary to push forward and complete this film was when the filmmaker “told a neighbor about the film and she assumed that the American citizens who were there were just fine—‘after all, they were Japanese, spoke the language, etc.’—and implied that there was no story.”

Beyond informing the world of this group of Japanese Americans, she wants audiences to determine their own takeaways or lessons. When pressed, though, Mary offers the following suggestion to the younger generations: “I would want all young people watching the film to think about what they would do to survive if caught by circumstances in a country at war with their home country, cut off from financial support and contact with their famil[ies].”

As Mary alludes to, and why this film is a must-see, is because Mary and Thomas successfully bring to life what could otherwise have proven to be nothing more than a dry, severely generalized history book version of what the average, nameless Japanese American stranded in Japan may (or may not) have experienced. Aside from some interspersed quotes/facts/figures, the vast majority of the documentary is an absolute pearl of oral histories encapsulating invaluable, firsthand experiences of a group of Japanese Americans whose story has too often been presented on the periphery, if at all.

Aside from the obvious tangibles that firsthand accounts provide, what they also hammer home in this film—and I think Mary would agree—are that they demonstrate how war separates families. Also, what they clarify is that, even though common themes may exist because they were all in the same basic situation, strandees’ opinions and experiences truly run the gamut. Moreover, Thomas chimes in that “[w]ar, in this case the Asian/Pacific Theater of WWII, is incapable of being defined as a conflict between distinct groups with uniformly differing ideologies.”

I would word it in a slightly different manner: war is nonsensical in many ways. (Just consider the hysteria that led to EO 9066.) As I watched this film, I could not help but feel for the Japanese American children who were prevented from returning to their parents in the U.S. Likewise, I scratched my head when this same group of U.S. citizens was conscripted to support the Japanese war effort by working in munitions factories and such. I also had a hard time wrapping my head around the fact that not only were U.S. citizens actually drafted into the Japanese army to fight against the U.S., but also that some were shipped off to Siberian labor camps as Japanese POWs.

These observations remind me of a WWII movie titled, Saints and Soldiers, that I watched several years ago but carry its images with me to this day. In it, U.S. soldiers come across German soldiers. An American was getting ready to fire on “the enemy” when he realized it was his good friend. To the dismay of his fellow U.S. soldiers, he refused to kill his close friend just because they were on opposite sides. (They captured him instead.) That scene has stuck with me after so many years because it illustrates how war can twist reality.

Of course, other viewers may come away with very different impressions. What is important is that everybody should view this film to give themselves the opportunity to take something away from it.

The filmmakers’ diligence is evident in the impressive number of firsthand experiences recounted in this film. More importantly, it is evident in the quality of those interviews.

In the following paragraphs, I highlight a few topics discussed in the film: being stranded in Japan, Japanese life during WWII including communicating with families in America and the Heishikan; conscription to support the Japanese war effort; Siberian labor camps; and the long-awaited return to the U.S. If these topics pique any interest, I encourage those readers to please view this film to find out more and do some research on your own, which is what I will most likely do once I finish this article.

Before the U.S. entered WWII, some Issei in the U.S. had been sending their children to live with relatives in Japan for various reasons. According to Taz Iwata, one of the strandees in the film, some parents wanted their children to grow up with Japanese values, culture, and education, before returning to the U.S. as an adult. As WWII carried on, but prior to Pearl Harbor, the film showed articles from newspapers such as the NY Times urging U.S. citizens to return home as soon as possible. Taz recollected that the U.S. consulate sent out letters instructing citizens to return to the U.S., but it did not mention anything about an impending war. Soon enough, it was too late. A couple of the strandees interviewed were coincidentally on the same ship headed back home when the U.S. declared war. The ship had to turn around, and there they were, stranded in Japan.

As the U.S. and Japanese governments carried out their war, from living (or trying to sleep) in constant fear of nighttime fire bomb raids to extreme food shortages, the strandees suffered alongside the general Japanese population.

Communication with families back in the U.S. was hit or miss. One of the interviewees said that letters, if they reached the strandees at all, would be redacted to the point they did not make any sense. Those letters, however, still served an essential purpose. That same interviewee and his grandmother would gain assurance that his parents and relatives in the U.S. were likely safe since they actually wrote them letters.

With communication being so difficult, strandees soon found themselves cut off from their families’ financial support, essentially trapped in Japan. Mary Tomita, an interviewee, reluctantly agreed to an arranged marriage because her free room and board ended with her graduation. Mary’s husband ignored her and left her to be an oyomesan, a servant to her mother-in-law. Unfortunately, it is not hard to imagine that many others fell into the same path because they had no other choice. There was a happy ending in Mary’s case, however, because she was known as a progressive woman who lived a full life, even authoring Dear Miye: Letters Home From Japan 1939-1946 before passing away. We can only hope that other Nisei women in her position had similar strong spirits necessary to have happy endings as well.

Other Nisei found themselves at the Heishikan, a school created to bridge the U.S. and Japanese cultures but later became known as a spy school. According to Before Internment: Essays in Prewar Japanese American History, “to train selected Nisei, the Foreign Ministry established a special school in 1939 called the Heishikan. …[S]uch Nisei, it was believed, would be the most effective in communicating with Americans.” The school’s curriculum had a good reputation, and it is likely that the Nisei who were admitted were appreciative of the free food and shelter in light of their financial situations.

Soon, money was not the only problem that strandees faced. According to author Samuel Hideo Yamashita, “[b]y 1943 the shortages of food became acute, and in 1944 the basic elements of a meal—rice, fish, soy sauce, and sugar—began to disappear from Japanese tables.” Although each had their own experiences, several interviewees discussed how the food shortage affected them. Some would go to the countryside to negotiate directly with farmers because there was not enough food sold in the cities. Others would catch fish, grasshoppers, snakes, or grow barley, sweet potato, whatever they could to sustain themselves. One interviewee even talked about how he ate so much banana squash that his palms and underside of his feet turned yellow.

If fire raids, lack of money, and very limited food were not enough, the thousands of stranded Nisei youth also faced being drafted to support the Japan war effort. According to Paul H. Kratoska’s Asian Labor in the Wartime Japanese Empire, “Japan needed manpower to staff the military services, manufacture war material and consumer goods…. The population of Japan proper, around 100MM people, was systematically mobilized.”

The stranded Nisei were no different. One interviewee spoke about how he sold sweet potatoes to the military, but that they were required to dry them out first because the military paid by weight and dried sweet potatoes were exponentially lighter. Eventually those sweet potatoes were used to make alcohol to fuel the Japanese war planes. He also collected pine tree roots, which were also distilled into a fuel source. One interviewee mentioned how his entire middle school graduating class was drafted to help out in munitions factories.

Basically, the general rule appeared to be if you did not have a job, the military could draft you. So strandees would try to get jobs that would satisfy the authorities that would be less unpleasant than what they might be drafted to do. Mary Tomita fell into this category of strandees; she found work listening to, and writing down, radio conversations between U.S. pilots.

Unlike the conscription of Nisei to support the Japan war effort, an individual was required to be on a Japanese family’s register to be drafted for service in the Japanese military. For the majority of Nisei stranded in Japan, the draft was simply not an issue; however, there were some who were adopted by relatives while living away from their parents. Those young Nisei unfortunately were subject to the draft because adopted children showed up on registers.

This was the unfortunate circumstance of Peter Sano, one of the interviewees in the film. He was drafted into the Japanese military and, while he was completing his basic training in Manchuria, Japan surrendered. Meanwhile, the Soviets declared war on Japan, took over Manchuria, and captured Japanese soldiers who were stationed in that region as POWs. Peter was shipped to a Siberian labor camp, not unlike those described in Nobel Prize-winning author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago.

Even if a discerning viewer is thinking of passing on this film because the person is already knowledgeable about strandees, I would urge them to pick up this film for Peter’s experience alone, as it represents a unique subset within Japanese Americans stranded in Japan. For even more insight, he has published a book titled, 1000 Days in Siberia.

One of Peter’s stories from the film that I will include here is from his days in basic training. He was told that since there were more Japanese soldiers than U.S. tanks, one of their training exercises would be to take a wooden box filled with explosives and practice diving under tanks…because the more enemy tanks that Japanese soldiers can destroy, the longer the Japanese military can sustain the fight. As he reflected back, he recalled that nobody really questioned the self-sacrifice that was being required.

Eventually, Peter found his way onto a repatriation list and returned to Japan. Like the others interviewed for the film, he ultimately made his way back to the U.S.

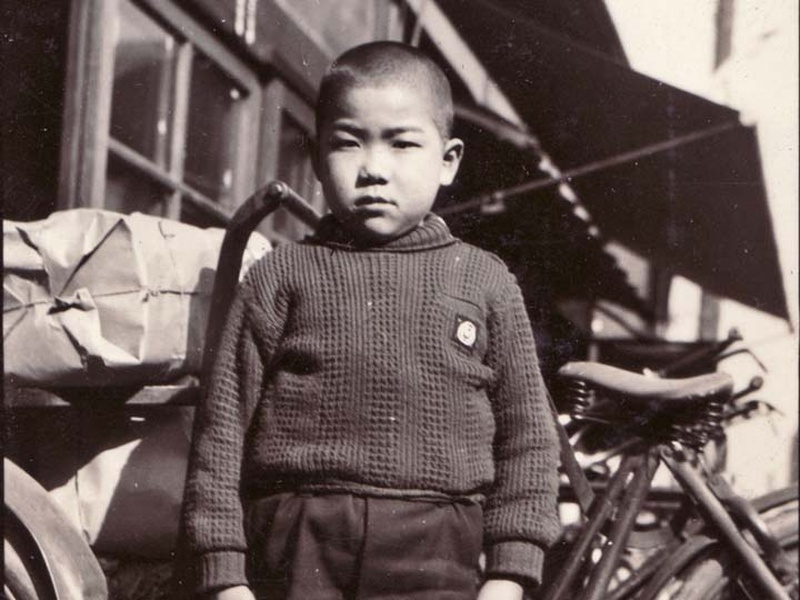

(Courtesy of Chizuko Mazawa)

Listening to the interviewees discuss their respective returns to the U.S., I observed that there was not an all-consuming joy of reuniting with their parents and families. It was not that black and white. I saw complex emotions from having to deal with parents who sent them away to another continent, to having created lives in that country, then having to leave it all behind to return “home.” Understandably, the concept of where is home seems to have become a bit muddied over their years overseas.

The following was Mary’s response to my observations:

“It appears to me that for this generation, absolute respect (filial piety) of parents was expected. But for a number of them, there continued to be resentment for having been sent to or just left without explanation in Japan. Their internal conflict was very, very interesting to me. Otherwise, I agree that their returns to the U.S. were quite varied and gave some unique examples of adjusting to life after the war that were somewhat different from the returns from the camps or the military or whatever else.”

Furthermore, Thomas frames the issue thusly:

“For many, their return was more or less dictated by how quickly they could get paperwork in order. For others, their stay/lives lasted decades in Japan. Also, when we arrived at the homes of the interviewees to ask them about their lives during wartime Japan, we would inevitably be exposed to photos and personal mementos on the walls along with anecdotes of the lives they lived in all of those subsequent decades that connected to the present day. Whatever complications they faced during the post-war transition, it was always interesting and inspiring to see the homes, families, and memories they forged afterwards.”

As educational as Nisei Stories is for its audiences, Mary and Thomas intended this film to be more than a gap-filler in the Japanese American story; it was deeply personal. Two of the individuals interviewed for this film were Chizuko and Shigemi Mazawa, Thomas’ grandparents and Mary’s in-laws. Thomas described that “[i]n the mid-nineties, shortly around the time my father recorded the audio tapes, I remember my grandparents having long conversations about their war experiences. It only happened on one or two occasions from what I remember. It may have been related to my grandfather’s recent Parkinson’s diagnosis, and a renewed desire to share their story while they still could.”

In the film, Chizuko shares many thoughts, including about her wedding day in a war-torn Japan. Regarding Shig’s contribution to the film, Thomas had this to say:

“Because the material from my grandfather came from more informal audio conversations with my father and grandmother, it was hard to isolate clips that were concise enough to be usable for the film. I had wished there was a way to share more parts of his stories, including the full version of his recollection of deciding to put a paper out for the Nippon Times the morning after one of the worst bombing raids Tokyo experienced during the war. He described them using the old non-powered printing equipment because there was no electricity, and rounding up all of the canned ‘filler’ stories they could find so they could put something together quickly. They then printed what they could and walked over the literally charred streets posting the paper to telephones poles and walls. I remember thinking it sounded like the most insane, but also sane, thing someone could do in the midst of such horror and destruction.”

By following through with this important documentary, what a wonderful family tribute as well as legacy to leave for their posterity.

In closing, Mary’s sage advice to all of us is to “record your family’s memories! One thing that kept us going was the advanced age of our interviewees. We are so grateful that we spent time with them and got their stories on video before they had cognitive difficulties and while they were still with us. Meeting these folks and hearing their stories was a wonderful experience—they were interesting and articulate and endearing, all of them.”

Thomas sums it up best when he says “the most engaging significance behind making or even just watching a good documentary is discovering that any historical topic is not really a single topic as much as a compilation of records and real personal experiences. The more you dive into that ‘topic’ the more you immerse yourself in very individual/human/relatable things.”

With the Nisei Stories film, I discovered the truth in Thomas’ statement and I hope others take the opportunity to do so as well.

* * * * *

Please join us on Saturday, June 20, 2015, at 2 p.m., as the Japanese American National Museum hosts a screening of the documentary, Nisei Stories of Wartime Japan, followed by a Q&A with mother and son filmmakers Mary McDonald and Thomas Mazawa, as well as Henry Yasuda, a Nisei who was attending school in Japan when WWII broke out.

If unable to make the screening, the DVD can be purchased online through Amazon, or the digital copy can be purchased through Amazon Instant Video.

© 2015 Japanese American National Museum