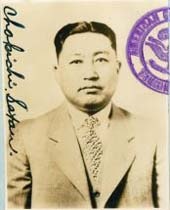

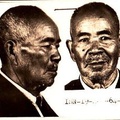

Satow was born in Miyagi-ken, Japan on January 15, 1885. He first arrived in San Francisco in 1903, before Angel Island became a U.S. immigration center, later returned to Japan, and then re-entered the U.S. in 1928 and 1931, when he was questioned on Angel Island. As a returning immigrant who had originally arrived before the restrictions of the 1917 and 1924 immigration laws took effect, he was allowed to return to the U.S.

Satow worked many jobs to make a living in the United States, working for ten years in Lakesburg, Idaho most likely in farming until moving to Sacramento County in 1913, where he picked fruit and harvested for different people. From 1915 to 1926, he picked fruit in Marysville, CA, then ran a boarding house for five years. Satow moved to San Francisco and was a houseman at the Toyo Hotel in San Francisco until 1936, when he returned to farming, picking fruit and other laborer jobs throughout California. In 1940, he returned to San Francisco and worked at the Yamato Billiard Hall on 1729 Post Street as rack ball tender and bookkeeper.

His wife Tsuru Shiba Satow lived in Fresno with her children from a first marriage for at least part of the time while he attempted to make a living throughout the state. She had arrived in the U.S. in Seattle in October of 1914.

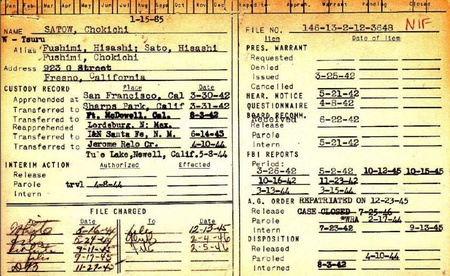

Chokichi Satow was initially apprehended in Fresno on March 26, 1942, then in San Francisco on March 30, 1942, and the next day was transferred to the Sharp Park facility near Pacifica, CA. The report of the Hearing Board during this time, agreed upon by the Assistant U.S. Attorney General, was that Satow should be interned.

Although there was no evidence of anti-U.S. actions or sentiments, the board had doubts about his truthfulness and believed that he was connected with “certain undesirable elements in the Japanese gambling groups in San Francisco.” The board also believed, despite Satow’s denials, that he was a member of the Sokuku Kai group which they felt had close ties with Japan. The Assistant Attorney General’s report concluded, “While the evidence against subject is not as strong as it might be, yet on the whole I believe the Board’s conclusion be warranted since they saw and heard subject testify. It should be noted that subject has petitioned for repatriation for himself and wife, giving his occupation as a farmer. His petition should be granted or, in the alternative, his internment should be continued.”

Satow’s Internment Card lists that soon after this decision, he was moved to Fort McDowell on Angel Island on August 3, 1942, then sent on an unknown date to Lordsburg, NM and then Santa Fe, NM on June 14, 1943.

Satow’s wife, Tsuru Shiba Satow, wrote to Edward J. Ennis of the Alien Enemy Control Unit of the Department of Justice from the Jerome camp in Arkansas in July of 1943 stating that her sons from her first marriage were involved in Defense Department work and that she was in a weak condition due to three operations on her stomach. She stated that Chokichi had never said anything against the U.S. nor had he performed any disloyal acts to the country, and requested that he be released and the two of them should be reunited.

Further research reveals that the sons were involved in the Military Intelligence Service, which conducted top secret work in the Pacific theater for the U.S. military. The MIS was predominantly comprised of Japanese Americans whose language, intelligence work and interrogation skills were credited by one U.S. general as aiding the war effort so much that it shortened the war by two years. Having not received any positive response, Mrs. Satow wrote to Ennis again in January, February and March of 1944.

As noted above, early in the detention process Chokichi Satow requested that he and his wife be repatriated to Japan. Many detainees requested this somewhere in their internment, often due to frustration over how they were incarcerated and thoughts that things would be better in Japan. Due to this status, in 1944 the Satows were to be sent to the Tule Lake Segregation camp, which was the site for those who were to be repatriated as well as others who had protested their status, resisted the draft, etc.

The Satows were finally brought back together at the Jerome camp in Arkansas in April 1944 so Chokichi could assist with his wife’s packing, before being sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center the next month.

A letter in the Satow file from October 1945, after the war was over, indicated that the couple wanted to return home to Fresno, so they might have changed their minds, like many other internees who had originally requested repatriation.

Despite this request, the Satows were sent to Japan on November 23, 1945. We do not know if they managed to return to the U.S. in later years, as many did thanks in large part to the efforts of Wayne Collins of the American Civil Liberties Unit, or if Tsuru’s sons who served in the Military Intelligence Service were able to return to California after the war. Please contact us if you can shed further information into the Satow story.

* Thanks to Adriana Marroquin for researching the Satow file in the National Archives and Records Administration center in College Park, MD and to Bill Greene at the San Bruno NARA office for his assistance.

*This article was originally published by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation.

© 2015 Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation