LOS ANGELES — Reverend Takeichi “Paul” Nakamura, 88, pastor of Lutheran Oriental Church in Torrance, California, who has been an integral part of the Manzanar Committee since its earliest years, has blended activism and faith in ways that few religious leaders have done before.

Rev. Paul, as he is known to his parishioners and so many others, will be honored by the Manzanar Committee at the 46th Annual Manzanar Pilgrimage on April 25, 2015, as the recipient of the 2015 Sue Kunitomi Embrey Legacy Award, named after the late chair of the Manzanar Committee who was also one of the founders of the annual Manzanar Pilgrimage, and was the driving force behind the creation of the Manzanar National Historic Site.

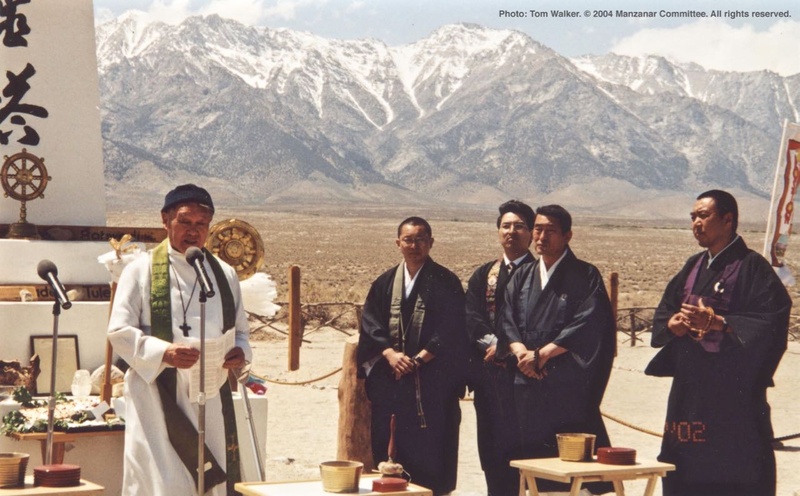

As much as Rev. Paul has done with the Manzanar Committee, his activism and contributions to the community, as noted in the first installment of this series, extends far beyond the boundaries of the Manzanar cemetery, where the interfaith service is held during each Pilgrimage, or the pulpit of his Torrance church.

In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, the Japanese American community began its demands for redress and reparations for their unjust incarceration in American concentration camps during World War II, and Rev. Paul was there to push for redress during the movement’s earliest days.

“He was with the Gardena Committee for Redress and Reparations from its very beginning, all the way through its merger with NCRR (National Coalition for Redress and Reparations; now known as Nikkei For Civil Rights and Redress), and was active in the redress movement well beyond that time,” said long-time community activist Roy Nakano, an attorney with the U.S. Small Business Administration. “His support for redress was unwavering, and it was one of the reasons he often served as one of our public speakers. That, and his skills as the pastor of his church, made him a natural at the bully pulpit.”

“Rev. Paul was one of the early faith leaders to step forward and embrace redress,” said former NCRR Southern California Co-Chair Alan Nishio. “While many other faith leaders were reluctant to get involved during the early stages of the redress campaign because it was seen as too divisive, or too political, Rev. Paul framed the redress campaign within the context of Christian values such as redemption and acknowledging wrongdoings.”

“Rev. Paul always embraced an ecumenical approach in working with other faith leaders and participated in numerous interfaith events that were held to support redress,” added Nishio.

Rev, Paul was rather modest when asked about his contributions to NCRR.

“When they met in Little Tokyo, I used to go to their meetings,” he said. “I got to know [the late] Bert Nakano, [former NCRR national spokesperson], who knew my wife’s family, and the great leaders [they had]. I stayed with them as long as I could.”

“I went to the [Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians hearings in Los Angeles in 1981],” he added. “I felt the pain [after hearing the testimony]. When NCRR went to Washington, D.C. [in 1987] to [lobby Congress], I went along with them, so I’ve been quite involved in the redress and reparations movement.”

Talk about an understatement.

“NCRR has always been very grateful to Rev. Paul for his leadership in gaining the support of the synod of the Lutheran Church of America at a critical time in the redress movement,” said NCRR Co-Chairperson Kay Ochi. “This national, highly influential endorsement reflected the type of broad public support that was important when conservative elements in the nation’s capital and across the country eschewed the idea of reparations.”

“The main thing I remember about Rev. Paul was his very open spirit and willingness to support redress in whatever way he could,” said NCRR Co-Chairperson Kathy Masaoka. “We often refer to the national support that NCRR and redress received from the Lutheran Synod, and that was all due to Rev Paul. He arranged for NCRR, probably Bert and Lillian Nakano, along with others, to give presentations to church groups that eventually led to the national endorsement. This was really critical to gaining the support beyond California and Japanese Americans.”

Rev. Paul, who received NCRR’s Fighting Spirit Award in 1987, was, as noted earlier, part of their delegation that lobbied members of Congress to garner support for the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

“A good example of his effort during the redress campaign was his participation in the 1987 NCRR lobbying delegation to Washington, D.C.,” Ochi recalled. “We knew that conservative Florida Congressman Charles Bennett would be a very tough vote to get, so we assembled a powerhouse lobbying team to visit him. The team included 442nd Regimental Combat Team/100th Battalion veterans Rudy Tokiwa and Bill Kochiyama, former Manzanar incarceree Hannah Uno Sheppard, and the Rev. Paul Nakamura.”

“At the end of their meeting, the Congressman said, ‘I’ll probably vote for the bill…I’ll vote for the bill,’ and he did,” Ochi added.

As Nishio pointed out, Rev. Paul was often at the forefront of civil rights issues. He never shied away from them.

“As a whole, I think that faith leaders, particularly African Americans, have been at the forefront of civil rights struggles and community activism,” said Nishio. “Within the Japanese American community, this has not been as prevalent, and I think Rev. Paul was someone who embraced struggles for social justice. I am not sure what pushed Rev. Paul toward activism, but I would assume that it was his own humble upbringing in Hawai’i, and his strong belief in the importance of faith in the fight for social justice.”

“I always found Rev. Paul to be a very grounded faith leader who was committed to grassroots activism,” added Nishio. “His early involvement with NCRR was a critical part of our efforts to broaden the support for redress within the Japanese American community.”

At The Center of the Civil Rights Movement…Literally

On March 7, 1965, some 600 voting rights protestors marched east out of Selma, Alabama, intending to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge into Montgomery, the state capital. Marchers were prevented from crossing by State and local law enforcement, who attacked them with tear gas and billy clubs. That heinous attack on peaceful protestors became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Two weeks later, about 3,200 protestors began another march from Selma. They would cross that bridge this time, marching twelve miles per day until they reached the steps of the Alabama State Capital building in Montgomery on March 25, 1965, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous, “How Long? Not Long!” speech.

Rev. Paul was among those who were there to witness and take part in history. Indeed, he flew from Los Angeles to Montgomery, joining protestors on the outskirts of Montgomery for the final day of the march where he saw and heard Dr. King.

Rev. Paul said that he would never forget the bone-chilling effect of the hate he felt that day along the route.

“That was quite an experience, to see the National Guard along the way, and to see all the people, with their organization and union banners, the churches, and whatever other groups there were,” he recalled. “All along the sides were the people. I remember, very distinctly, the people standing behind the National Guard—the stare they gave you. You could feel it. It was very uncomfortable. You could feel the hate and anger coming from them. I never forgot that.”

Rev. Paul indicated that joining the march in Montgomery was par for the course for him—nothing out of the ordinary.

“My church, St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, was in Los Angeles, across from USC (University of Southern California), and I had African Americans in the congregation,” he explained. “It was a multicultural church, and I was very much a part of the community, so it was normal for me to get involved in something like the Civil Rights Movement.”

The Manzanar Pilgrimage and the Manzanar Committee. NCRR. Redress and reparations. Montgomery and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. That’s an impressive resume for an activist clergyman.

“It was no mistake that in 1965, he went to Montgomery, Alabama and he participated in the Civil Rights Movement,” said Manzanar Committee Co-Chair Bruce Embrey. “Rev. Paul clearly personified the link between the broader civil rights and social justice movements and the rise of the movement for redress and reparations. His passion for justice and civil rights carried over into his work with the Manzanar Committee, making us all that much stronger.”

“Rev. Paul is a true, unsung hero in both the Japanese American and religious communities, not to mention the broader movement for civil rights.”

*This article was originally published on the Manzanar Committee blog on April 19, 2015.

© 2015 Gann Matsuda