“Objects have the longest memories of all; beneath their stillness they are alive with the terrors they have witnessed.”

—Teju Cole, The New York Times Magazine

An immaculate 1930-ish Singer sewing machine—richly embellished with gold filigree detail, a solid wooden folding table, and an intricately curved cast iron stand—sits in the den of Flora Shinoda’s home in the Leimert Park area of Los Angeles. Its impeccable design and cherished care are reflected in the fact that the nearly octogenarian machine still works today. Wrapped around the body of the machine, there is a delicate handmade fabric collar to conveniently hold straight pins in place. Sewn together by its original owner, this small detail is a sign of an instrument that has seen heavy use by an experienced seamstress.

If an object like this could speak, it would certainly recall its turbulent life spent during the deadly war years in Japan. From 1941 to 1953, this trusty Singer survived destruction and devastation in a country that was riddled with fiery air strikes estimated by experts to have killed more than 100,000 civilians (actual statistics vary). Before Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 67 Japanese cities were targeted by B-29 Superfortress strategic bombers carrying napalm designed to set incendiary fires that killed more people than the two atomic bombs combined. In Shizuoka alone, the area lying halfway between Tokyo and Nagoya, 1,952 were killed and 12,000 people injured in a single day.

In 1945, as the Allies entered the fourth year of fighting in war-torn Japan, Flora, her mother Hideko, and her younger sister Kay, along with their faithful Singer sewing machine, were living in a typical Japanese wooden house near her grandparents’ home in Shizuoka, Japan, after having emigrated there from East Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights. Born in Seattle, Washington, Hideko had left the United States at age 3 to spend her childhood in Japan until moving back to the Seattle area at age 18 with her father and brother. In 1922, after getting married in Seattle, she and her husband moved to Spokane, where Flora was born. In 1927, they moved to Boyle Heights in Los Angeles where Kay was born. When the children were 8 and 11 in 1936, they were sent to Shizuoka with their uncle to live with their grandparents and to learn Japanese culture. Five years later, just one month before the attack on Pearl Harbor, their mother Hideko decided to rejoin them, little aware of the disastrous events that were about to ensue.

Hideko arrived in Yokohama in November 1941 aboard the Tatsuta Maru, the final passenger boat to leave America bound for Japan during the prewar years. A food poisoning outbreak aboard the luxury liner sent her to the hospital for several days after the ship’s arrival. The Tatsuta Maru played a critical role in the Japan-U.S. conflict: one month after Hideko arrived, the same ship departed for San Francisco carrying a shipload of expatriates back to America. In an attempt to divert attention from the Pearl Harbor attack, the ocean liner was scheduled to arrive December 14 through Honolulu to pick up passengers bound back to Japan. A week earlier, on the early morning of December 7, it was secretly ordered to turn around before it reached Pearl Harbor. Even those in charge on the ship were not aware the ship was being used as a decoy.

Meanwhile in Japan, Hideko settled in Shizuoka after finally being reunited with her daughters. She turned immediately to sewing as her only way to make ends meet at a time when food was scarce and rations small. She had honed her craft as a seamstress in America and was fortunate enough to own the highly prized Singer sewing machine. Made by the internationally renowned company whose machines dated back to the 1800s, their products were considered far superior to any made in Japan. Hideko would boast that she could make anything with this machine. A talented seamstress, she also filled a need by teaching sewing to young Japanese women wanting to learn to make more modern garments than traditional kimono.

Like any other family desperately struggling to survive in an area that was riddled with air raid sirens, Hideko and her daughters were constantly taking precautions to avoid being struck. B-29 bombers hovered in the skies above their home near Mt. Fuji, and they were warned to keep their lights down so as not to attract attention. Above all, Hideko knew they had to protect the precious sewing machine she had sent all the way from America. There were three other Japan-made machines being used in her classes, but those were not nearly as valuable as the Singer. Besides, her evening sewing classes were eventually forced to close because of warnings to turn all the lights off and put blankets over the windows to avoid being seen at night.

The family built a step-down area in their home, much like a bomb shelter, where they could store their prized Singer. The small space had just enough room for the sewing machine—disassembled into three parts—along with extra bolts of fabric, emergency food, family photographs, and important papers. The family knew that if the machine were destroyed, their sole source of income would vanish. In order to protect it, they would carefully unscrew two bolts on the top of the cabinet and take apart the shiny black machine from its wooden base. The elaborate cast iron legs were then disassembled so the machine could be folded into the opening in the floor.

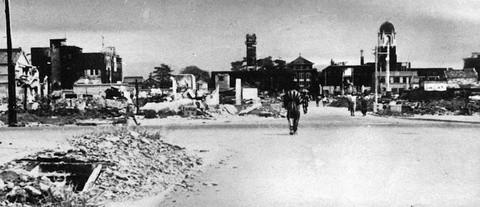

Then one summer day, the unspeakable happened. In the evening of June 19, 1945, Hideko and daughter, Flora, were at home when the napalm bombs struck. Their home was set afire and destroyed along with nearly 27,000 other houses. They made their way to the river to protect themselves from the fires. They spent the night waist deep in water as brush and debris flowed past them down the riverbanks. All the while, they shoveled water to keep the burning brush from getting close to them. When the bombing finally ceased and daylight broke, they were met with a horrific sight. As they slowly made their way back home, they had to step carefully over charred bodies in the streets everywhere. A haunting memory was the burned remains of a circle of young schoolgirls lying dead still holding hands. The one-day reign of terror in Shizuoka resulted in 66% of the city being destroyed.

After the younger daughter, Kay, who was in another part of the city during the attack, rejoined them, the three tiny women then did something remarkable that under normal circumstances would have been considered almost impossible. They returned to their burned home to retrieve their cherished Singer, wrapped the three sewing machine parts in furoshiki, and carried each of the extremely heavy, bulky sections on their backs as they made their way to the train station. Still carrying the weight of the machines, they traveled by train to Saitama, nearly 200 miles away, before being met by relatives there. It took extraordinary strength to ensure that the one thing that meant the most to their survival was rescued. The Singer sewing machine was their salvation.

Hideko indeed used it to earn a living during the even more difficult postwar years. As people were starving in the streets of major cities, the family was able to subsist in the smaller countryside area of Saitama and the mountainous region of Nagano as Hideko made clothes and taught sewing, partially in exchange for food. Flora learned to help her mother with her sewing duties, not because it was something she wanted to do but because it was needed.

The three women eventually returned separately to the United States by 1953. To avoid working in a garment factory, Hideko used the same Singer sewing machine that she once carried on her back to revive her career as a seamstress and designer. She worked at home and lived until the ripe age of 92. Her daughters, one now 90 and the other 86, have lived long enough to share their Japan war stories with their children and grandchildren, but like many who survived the war, they remain reluctant to talk about that indescribably difficult time with others. They say it is impossible to know what happened without witnessing it firsthand. Besides, Flora says, “It’s important to go forward.” Flora further explains that in spite of facing the horrors of war, she also learned valuable lessons from what she and her family endured.

The Singer sewing machine bears silent witness to their story and to a history sadly in danger of being forgotten. In this year of the 70th Anniversary of the bombing in Japan that includes Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is notable that more and more people are opening up about their unspoken pasts to share stories of survival and endurance. Fortunately in this case, a Singer sewing machine—sturdy and intact—spawned a tale of the triumph of the human spirit.

* Author’s note: This story was based on the recollections of Flora Shinoda. I would like to give special thanks to her daughter, Lillian Shinoda, for encouraging her mother to share her story, and to Mary Karatsu for recognizing its importance and bringing it to my attention.

© 2015 Sharon Yamato