Arizona

The section on Arizona in the "Centennial History" begins with the opening line, "The pioneering efforts of the Japanese who fought through the scorching heat of Arizona, symbolized by the desert, cacti, and cowboys, to build the farmland we know today is admirable." It also goes on to say, "The Japanese are great benefactors to Arizona agriculture."

The first agricultural activities by Japanese people were in 1905, when 120 workers were sent to work on a sugar refinery company's plantation by the Japan-America Industrial Association in San Francisco. Since then, various kinds of vegetables and strawberries have been cultivated in various places.

The following is written about the characteristics of Japanese agricultural history in the state:

"Just before the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, Kajuro Kishiyama began cultivating spring cut flowers (such as souks and snapdragons) on the slopes of South Mountain in southern Phoenix, and after the war, Nakamura, Watanabe, Nakagawa and others followed suit, and the flower gardening industry flourished in the area."

There was also a Japanese person who came to this area earlier than agricultural work, such as Hachiro Onuki, who came in the early 1980s.

"The Phoenix wagons of those days were literally covered wagons, and most of them were built during the cowboy era, driven by the gold mining fever. Onuki carried drinking water to the miners, which he exchanged for gold bars to make money. He used that capital to set up gas companies, electric power companies, and train companies in Phoenix in collaboration with white people, and he was also a great benefactor to the development of the city of Phoenix."

At one time, he experienced severe ostracism.

Apparently there was a Japanese community in Arizona, and the relevant historical facts can be found in the records of this community, which in their "Prewar Chronological History" covers the period from 1899 to 1931. Let me introduce a few of them...

"1899: Shuzo Fukunaga (Hiroshima), Onmon Saito (Iwate), and Kohei Tanaka (Nagano) open a Western-style restaurant in Phoenix."

"1918 - The economy was booming and many new rich people returned to Japan. Mr. and Mrs. Sakamoto went to see the Grand Canyon for the first time by car."

"1926 = Japanese Language School established in April"

The Japanese population in Arizona was 281 in 1900, grew to 371 in 1910, 550 in 1920, 879 in 1930, 632 in 1940, 780 in 1950, and 1,501 in 1960.

At first, they were agricultural and railroad workers, and then the number increased due to agricultural development. However, it seems that the agricultural development of Japanese people was met with quite strong opposition at one time. In particular, white farmers flocked to Arizona during the depression that began in the 1930s, and attacked the Japanese who had been successful earlier. It seems that the movement was quite intense at one time.

"In particular, the anti-Japanese incidents that arose from late July 1934 resulted in 10 direct assaults, 24 cases of assault evidence, and 69 victims..."

To the Poston Relocation Center (Camp) for Japanese Americans

When the Pacific War began, Japanese Americans in the state were interned at the Meyer Assembly Center, and then at the Poston Relocation Center in the desert. A year later, those who had entered from Arizona were allowed to leave. Thirty percent of those interned remained until the camp was closed at the end of the war, and 70% went through the process of leaving to return home.

After the war, Japanese Americans settled mainly in Phoenix and Glendale, as well as Mesa, Tempe, Peoria, Tolson, Scatchdale, and Tucson.

Regarding the people who were in the relocated addresses (internment camps), it was said, "After returning home, they ended up homeless, but they overcame hardships and worked hard to start afresh and rebuild, and today, there is a huge increase in the number of people purchasing land, houses, etc., more than before the war, and they have built a solid foundation."

* * * * *

Colorado

Colorado, located in the center of the United States from north to south, is slightly west of the center from an east-west perspective.

According to "Centennial History," it writes about the early Japanese people, "Around 1893, there were already several Japanese living in the capital, Denver. Many people traveling east would stop in the city for a period of time, staying there for a year or a year and a half to save up money for their journey, and then many of them would set off on their next journey east. At one time, the number of Japanese residents was said to have reached more than twenty."

After that, the number of Japanese people gradually increased, and "by 1897 the Nitta Bamboo Crafts Shop was already in operation. A year later, there was the Ohno Western Restaurant on Lamaree Street (now Denver's Japanese Town), and Ide Kyokichi's bamboo carpentry shop near the Courthouse."

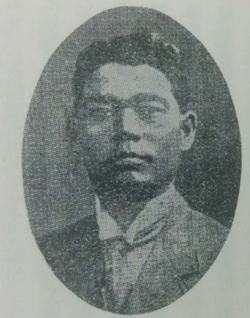

Pioneer, Naoichi Hokazono

The first Japanese person to reside in Colorado was Matsudaira Tadaatsu. He was the younger brother of Matsudaira Tadayoshi (Viscount) of the Shinshu Ueda Domain, and after completing his studies in Virginia in 1872, he worked as an engineer for the Union Railroad Company and other roles in the Midwest development project. Around 1886, he worked as an assistant to the Colorado State Inspector of Mines. He married an American woman in the area and had one son and one daughter, but died of illness two years later.

Also introduced as an early "pioneer" is Sotozono Naokazu, a native of Oita Prefecture. He came to America in November 1893 at the age of 20, travelling from San Francisco to San Diego and then to Denver, where he engaged in large-scale contracted sugar beet cultivation. He later founded "Sotozono Construction" and sent Japanese workers to various labor contracting businesses, as well as to railroad and coal mining companies.

At that time, a difficult project was underway to build a national highway in the national park on the Rocky Mountains, and this was completed by Japanese workers led by Hokazono.

The Centennial History states, "An immortal monument to the Japanese people was erected in a corner of the highest point in the Americas. During this difficult construction work, 34 Japanese men were killed in a tragic attack by dynamite."

Hokazono also worked on waterworks and power generation projects at dams in Wyoming.

"Furthermore, he and his group built an iron tower 80 miles between the Boulder Town power plant and the city of Denver, through which high voltage electricity could pass, providing light and power to the 350,000 citizens of that city at that time."

A special warehouse was set up by Sotozono Construction at Denver's Union Station, where 400 horses alone were kept.

Urging fellow citizens to exercise self-restraint in anti-Japanese sentiment

The number of Japanese migrants to Colorado increased rapidly from 1900 to 1905, and according to a 2009 investigation committee, there were 3,550 Japanese residents, of which 55 were women and children. By occupation, there were 400 railroad workers, 300 coal miners, 150 factory workers, 500 domestic workers, and 500 farmers.

In 1909, the family estimated they were cultivating a total of 18,500 acres, producing sugar beets, vegetables, cantaloupe, wheat, pasture grass, and corn. Most of the land they cultivated was rented or sharecropped, but they also owned about 500 acres.

In this way, the activities of Japanese immigrants became more active, but at the same time, from around 1907 anti-Japanese sentiment began to spread, and the following year, in 1908, the Asiatic Exclusion Society was organized in Denver. The reason for the anti-Japanese sentiment was that Japanese people were working for low wages, excluding white workers, but the direct cause was said to be "the movement of the Japanese-Korean Exclusion Society in San Francisco."

In response, the Colorado Japanese Council (chaired by Naokazu Hokazono) visited anti-Japanese newspapers and labor organizations to convey the true feelings of the Japanese, and requested police protection. In addition, they issued warnings to the Japanese to exercise self-restraint.

The contents of the guidelines include "Do not go to gambling dens, brothels, or other unscrupulous places," "Do not walk the streets while drunk and make a fool of yourself," and "Do not take up a job where you take the work of a white person." It is clear that Japanese people are extremely careful about their behavior.

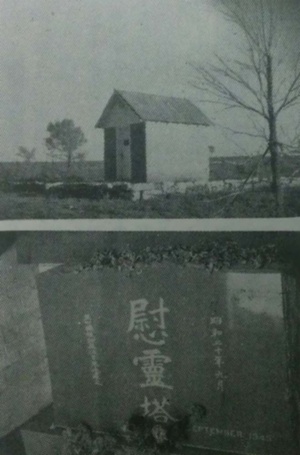

The Centennial History's introduction to Colorado tracks development by region, and in the Granada-Hurley area, it mentions the wartime "Amachi Relocation Center" (Granada Internment Camp).

"At its peak, the Amachi Relocation Center, which opened in 1942, housed approximately 8,000 Japanese people, and it was an unusually lively place, just like a large farming town had appeared on the Colorado-Kansas border."

Among the detainees, some were released at the request of farmers in the region and went to work during the busy season. Many also died, and impressive memorial halls and monuments were built for them.

Moving forward a little in time, in the spring of 1941, before the war began, Japanese people in Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming held a conference called the "Japanese Current Affairs Conference in the Three Shandong States" to discuss how to respond to the current situation. Representatives from over 20 organizations gathered, and it was "probably the largest conference ever held in the three Shandong states."

As the war drew to a close, the Japanese community in Colorado...

"In January 1945, when the evacuation order to the coast was lifted, many people returned, longing for their old homes, and although the area is showing signs of marked decline, it still retains a population of over 3,300, has two daily newspapers, impressive temples of both the Buddhist and Buddhist sects, and several public organizations, and still retains the vestiges of a Japanese town."

The Japanese population in Colorado was 48 in 1900, but exceeded 3,200 by 1930, decreased temporarily during the war, and by 1960 had risen to 6,848.

(Note: I have used the original text as much as possible, but have made some edits. Titles have been omitted.)

*Next time we will introduce " Japanese Americans in Nebraska and New Mexico ."

© 2015 Ryusuke Kawai